John Harte: Breaking and restoring our life support system

Systems-thinker John Harte gives a roadmap on how we can use the same interconnectedness that is spurring catastrophe to instead promote health and sustainability.

Human society is complex, with myriad interconnected components.

The proverbial butterfly wings are flapping everywhere, triggering unpredictable responses of a magnitude far greater than could be anticipated from the tiny metabolism of the "butterfly."

Thus, human contact with a single bat or pangolin in some Chinese market may be what has now brought civilization to its knees.

Ecologists have argued that complexity and interdependency are what make ecosystems stable— resistant to disproportionate responses like what we're experiencing during the coronavirus pandemic. Simplify the ecosystem, cut the connecting cords, and you end up with a system highly vulnerable to disturbance.

Indeed, in systems that have slowly evolved over countless millennia, that foundational principle has a good deal of truth.

But complex society did not evolve in the Darwinian sense; unlike a population of beetles, civilization is not, primarily, the product of millennia of trial and error.

Our jury-rigged society is interlinked in a way that causes the failure of one component to bring about the failure of others. Thus, in the current pandemic, huge gaps in the U.S. public health and medical support system, including gaps in access to affordable medical care and a scarcity of hospital facilities to treat Covid-19 victims, may be leading to the potential collapse of our economy, including our food, transportation, education, and social welfare systems, as well as our capacity to prevent or treat the disease itself.

When a minority among us hold the majority of political power, spending priorities do not favor building a healthy and sustainable society for all, and thus the many inequities in our economic system make it more likely, not less, that everyone, including the wealthiest among us, will contract the novel coronavirus.

Environmental disconnect

Deforestation in Papua New Guinea. (Credit: Rainforest Action Network/flickr)

Over the past decades it has become clear that each anthropogenic stress that we impose upon our environment exacerbates the consequences of the other stresses.

Deforestation, which destroys habitat for biodiversity, also contributes to global climate disruption; global climate disruption not only threatens food-crop production but also reduces the nutritional content of the food we do produce; the loss of biodiversity reduces the capacity of our planet to provide numerous goods and services necessary to sustain humanity.

And linked to all these issues, increasing numbers of people on Earth make even more destructive all of the consequences of interdependency, including making it more difficult for effective governance that can take the necessary actions to reduce the threats.

Education’s blind spots

Universities are another node in this system of destructive linkages.

We are, of course, indebted to our medical schools for training the medical researchers and health workers upon whom our lives depend.

But the business schools and departments of economics in these same universities are now contributors to future catastrophe.

Graduates of their programs are trained to promote the fantasy of perpetual growth and untrained in areas that would provide insight into the true sources of wealth and well-being on our planet. Economists are not taught the fundamentals of ecology; engineers are not trained in history; business students are not taught enough science, law and ethics; and, my pet peeve, almost nobody is taught enough math!

What perpetuates this archaic system of higher education?

It is in part the priorities of the very civilization it has helped to produce. Many of the smartest minds coming out of graduate schools are siphoned off into legalized gambling, otherwise known as market trading, or to work with the leaders of organized crime, otherwise known as corporate law firms.

The wealth they accumulate over their careers makes society poorer, not richer, as these wealthy benefactors endow business schools but not programs in systems biology.

Flipping to the “sweet side of synergy”

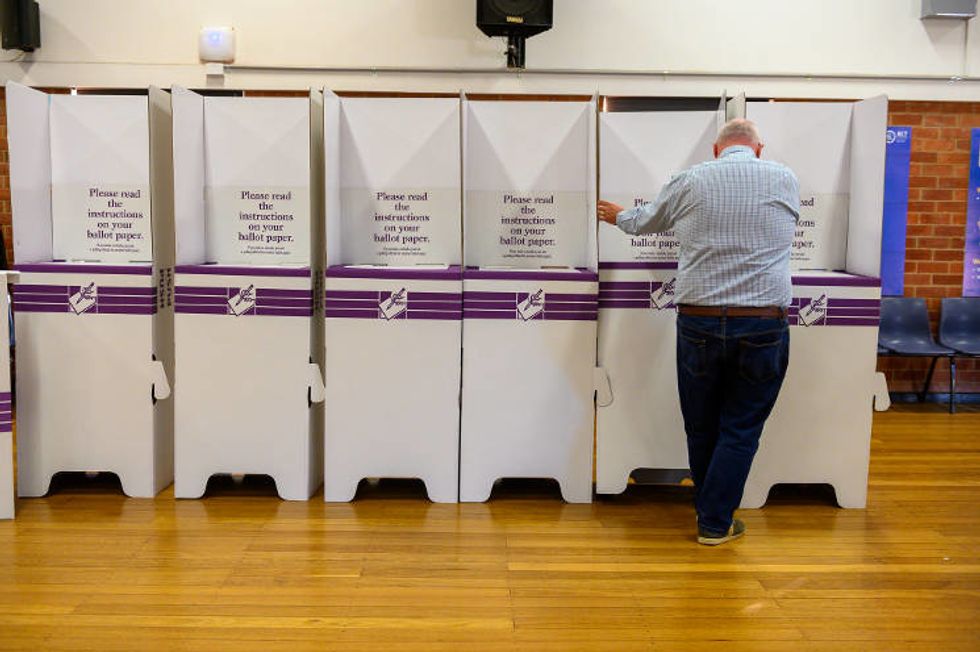

Building democracy—and having elections decided by people, not corporate interests—will be key in restoring the power balance in our society. (Credit: AEC images/flickr)

I refer to the entire situation described above as "the sinister side of synergy."

On that side of synergy, interconnectedness results in mounting catastrophes.

But there is good news as well and it stems from the same system properties that lead to harmful outcomes. Suppose we do take thoughtful action to reduce pollution, inequality, overpopulation, wild animal markets, and all the other triggers of impending catastrophe.

Then those actions trigger consequences that are also generally beneficial to the health and sustainability of society. The synergies begin to act in our favor.

Today the power balance in our society favors actions that lead to sinister outcomes. Reversing that situation, and achieving a society in which rational decisions are made and the sweet side of synergy flourishes, will not be easy.

But here are some necessary steps.

- Building democracy. For democracy to operate in practice as it is supposed to in theory, elections must be decided by a majority vote of all who are eligible and wish to vote, and limits must be imposed on the private funding of candidates for public office.

- Population and women's rights. Women worldwide must be given the right to exercise freedom to make their own reproductive decisions, to have freedom over their own bodies. Contraception must be universally obtainable.

- Sustainable energy. For the survival of civilization, the transition from fossil fuels to sun, wind, and greater efficiency of energy use must be expedited. There is no magic policy prescription; a combination of regulations, shifting subsidies, tax incentives, and education will be needed, as will an overall reduction in total energy consumption.

- Health care for all. As the current pandemic teaches us, affordable health care must become a basic right for all citizens. Greater preparedness for the next pandemic, and surely there will be one, is also critical. We will learn a good deal over the coming months—and, whatever we learn, the lessons from Covid-19 should be implemented expeditiously.

- Food security. Even with concerted action to reduce the intensity of global climate disruption, adequate water supply will remain a critical issue in food production. Reducing production of, and finding more efficient irrigation methods for highly water-demanding crops are critical. Organic farming appears to be the only viable long-term solution to food production if we want to avoid the risks of toxic pesticides and herbicides both in our food and in the runoff water that we drink downstream. Husbandry also needs reform to curtail the overuse of antibiotics in farm animals, which encourages potentially harmful mutations of pathogens, and to eliminate raising farm animals such as pigs and ducks under conditions that lead to the origination of diseases that can transfer to humans. Going vegetarian may be society's only option for sustainability.

- Reducing inequality. Inequality of income and wealth is a kind of disease, and it, too, is pandemic. It weakens society and the power imbalances that create it are contagious. In addition to the ethical reasons for reducing inequality, doing so would probably result in a decrease in luxury consumption that harms the environment without providing life-sustaining benefits. Taxation is clearly the best cure for this disease.

- Save biodiversity. All of the actions prescribed above would help stanch the increasing rate of loss of wild plants and animals. But they will not be enough. Protecting vast areas of natural habitat, where the human presence is minimal, is essential.

- Fix universities. If I could, I would require that nobody graduates from my university with a degree in economics, business, law, engineering, or public policy without having taken a serious course in ecology and another one on thermodynamics and the entropy law. Ecologists should also learn economics. Indeed, let there be one major for all, "Complex Systems," with different emphases within, but a common core of knowledge.

- Enhance rationality. Millions of Americans have doubts about whether global warming science is real and a substantial portion of our population has doubts about evolution. Denial of science can be a relatively harmless pastime provided it is done in the privacy of one's home. Indeed, the Constitution guarantees all of us the right to spout nonsense. But now anti-science threatens to alter the curricula of our public schools, as the creationists would do, and threatens to tear the legal fabric that protects our environment and our society. The citizens of a democracy must speak out in defense of rationality. When political leaders try to overturn the regulations that protect citizens and our natural heritage it is not merely overturning a legislative legacy of several decades. It is overturning a 500-year legacy of civilization that has steadily replaced faith in irrationality with acceptance of science. The long-term consequences of such actions will reverberate through the coming decades in ways that will degrade far more than the health of our environment and our material well-being; they will erode a very foundation of civilization.

In this together

Children from Chenglong Elementary School looking at environmental art. (Credit: Timothy S. Allen/flickr)

Let's end with a thought experiment.

Imagine you are setting forth on a long journey with a group of people that you do not know very well. The journey will take you to a place neither you nor anyone else has ever been. Many hazards will be encountered: water supplies and food are limited, you will all have to endure crowded conditions, you will be exposed to chemicals that no person has ever been exposed to, the climate in the land you are going is unlike any you have ever experienced, and you are virtually certain to encounter new and highly infectious diseases for which you currently have no medicine.

On top of all that, your fellow travelers hold competing values and goals. For one thing, they have very different attitudes about the role that scientific facts and understanding should play in decision-making.

There are clear signs that the current leader on this journey is not capable of distinguishing fantasy from reality.

This should scare you, for you cannot go on this journey alone; you are all utterly dependent upon one another, and, in particular, on the capacity of all of us to have a shared knowledge of how the world works.

All of humanity is en route; and unlike our critical response to the current pandemic, staying home is not an option.

John Harte, an ecologist originally trained in physics, has devoted his career to seeking the simplicity on the other side of complexity. He has taught in the University of California, Berkeley's Energy and Resources Group for the past 45 years.