Disaster by choice: The need to create a culture of warning and safety

The tornado, the earthquake, the virus are not to blame for our decisions.

Disasters are not natural. We—humanity and society—create them and we can choose to prevent them.

Stating that natural disasters do not exist because humans cause disasters seems insanely provocative. We witness nature ravaging our lives all the time: from a city underwater after a storm roars off the Atlantic to rows of smouldering houses after a wildfire to the dust rising from the ruins after an earthquake.

How could we withstand the 250 mile per hour winds of a tornado, faster than Japan's bullet trains, or the 2,200ºF temperature of lava, hotter than many potters' kilns? How would we feel if an "expert" lectured to us that it was not nature's fault, as we sifted through the few photos salvaged from the pile of debris that was once our home and our life?

Yet even when we cannot keep our infrastructure standing, we can stop people dying, we can protect our most valuable possessions, and we can learn to deal with devastation. The disaster lies not in the forces unleashed by nature, but in the deaths and injuries, the loss of irreplaceable homes and livelihoods, and the failure to support affected people, so that a short-term interruption becomes a long-term recovery nightmare.

The New York National Guard loads cars with meals to distribute to those in quarantine due to COVID-19. (Credit: The National Guard)

Even the COVID-19 pandemic is not a natural disaster. We know that new viruses emerge and infect us all the time. We could have improved our monitoring for and response to emerging diseases, which means—at minimum—not silencing and intimidating health professionals who report that something might be happening. And, long before, we must build robust health systems and health coverage, so that countries can be confident of taking care of a sick population. Then follow the long-ago-shelved pandemic plans that would have told the world how to deal with the new coronavirus without it becoming a pandemic forcing so many of us into lockdown for weeks.

The tornado, the earthquake, the virus are not to blame for our decisions.

They are manifestations of nature that have occurred countless times over the aeons of Earth's history. The disaster consists of our inability to deal with them as part of nature. We have the knowledge, ability, technology, and resources to build houses which are not ripped apart by 250 mile per hour winds. If we choose to, we can create a culture with warning and safe sheltering.

Lava at 2,200ºF and a tsunami higher than our building are harder to ride out. But we can shun places likely to be hit by them or we can create a culture that understands and accepts periodic destruction, again with warning and safe evacuation, to permit swift rebuilding afterwards. The baseline is that we have options regarding where we live, how we build, and how we get ourselves ready for living with nature.

Many of the choices we make currently permit death and devastation. They create the conditions for disasters, not nature.

Inequities, underdevelopment, and marginalization

January 12, 2020, marked the tenth anniversary of Haiti's earthquake disaster, killing at least 150,000 people and possibly up to double this number, the vast majority of them poor Haitians living in inadequate constructed dwellings. Yet knowledge of Haitian earthquakes extends back centuries, with many previous earthquakes around the country experienced and recorded.

Despite this knowledge of seismicity, little action was taken.

Why was the infrastructure in and around the capital city so poorly constructed? Why were so many people poor, leaving them with no choice but to live in these buildings without hope of improving them? Why did even many affluent parties, from the country's president to the United Nations to the developers of luxury hotels, not enact basic earthquake safety principles?

These questions were being asked in 2010: a meeting on tackling disasters in Haiti, highlighting seismic safety, was concluding on January 12, 2010, when the earthquake rumbled through.

The overwhelming inequities, underdevelopment, and marginalization precluded a quick fix. Haiti, as a country, is not especially poor or under-resourced, but the scale of inequality is horrifying. Centuries in the making, all these problems could not be easily tackled or solved.

It takes time to put up tens of thousands of buildings that lasted barely a minute on January 12, 2010. It takes time to create a city rife with informal settlements, without basic services, and lacking planning regulations, building codes, and institutions to monitor and enforce such laws.

It takes time to produce a culture of day-to-day bustle across exposed electric wires, through haphazard doorways, and around informal structures. The earthquake lasts seconds, but creating a society accepting infrastructure that cannot withstand earthquakes—creating the vulnerability, which creates the disaster—takes decades and centuries.

A family awaits treatment at a Red Cross First Aid Post in Port-au-Prince, Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. (Credit: American Red Cross)

Human-created vulnerability

Same with the recent bushfires in Australia. The country has good reason to fear such flames. The incongruously named Ash Wednesday fires of February 16, 1983, killed 75 people across two states in 12 hours. Tasmania lost 62 people to the Black Tuesday fires of February 7, 1967.

The most lethal Australian bushfire disaster occurred exactly 42 years later on February 7, 2009, or Black Saturday: 173 people died and 414 were injured.

Indigenous Australians managed fires for tens of thousands of years. They set controlled blazes to alter the environment for maintaining tracks, trapping animals, and avoiding the build-up of burnable fuel that could lead to large conflagrations.

Over time, Indigenous practices adapted the ecosystems to support plant species that could survive low-intensity bushfires, actually using fire to propagate. Fire was part of land use and land management, integrated into human needs among other environmental adjustments, although we do not really know how many fire disasters the Indigenous Australians might have caused nor how many of them perished in the flames.

Europeans imported and imposed a different perspective of bushfires. Flames were presumed always to be dangerous and damaging, so they were suppressed and fought. As settlements expanded into the bush, fires indeed became highly destructive and lethal, reinforcing the combat mode.

The 2020 fires continue this pattern. Despite the heat wave and the fires' intensity and extent, plenty could have been done over the long-term to avoid the witnessed catastrophe. Over past decades, cities and towns have expanded significantly into burnable areas.

Home owners can design and maintain their houses and land to reduce the chance of them catching alight during a bushfire. No guarantees ever exist of saving property, but we have seen the difference in Australia this year between those whose dwellings survived and those who sadly lost everything or who tragically perished while staying behind to defend.

The key is preparing years in advance, including being ready to lose one's home, knowing that fires are part of the ecosystem and could happen any year, even if now being much more intense and expanding in range due to human-caused climate change. The fundamental cause of the Australian bushfire disasters was creating vulnerability to the environment, no matter what the fire hazard does.

A firefighter from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management assists with Australian bushfires in January. (Credit: BLMIdaho)

A path forward

For the environmental events and processes we can deal with by reducing vulnerability, which are most of them, we are the real causes of disasters, not nature. Inadvertently or deliberately, in knowledge or in ignorance, disasters emerge through human choices, actions, behavior, and values. Closing this chasm between what we know and actually using this knowledge is not easy.

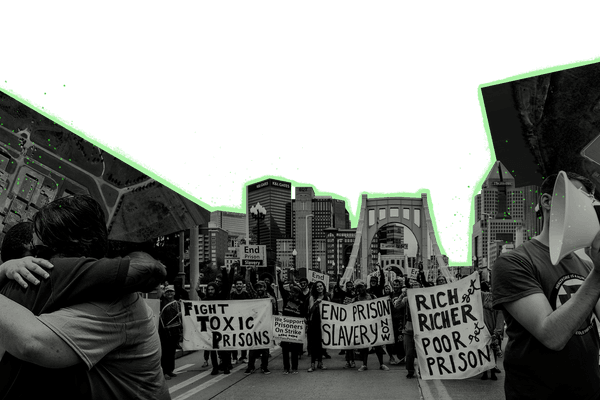

Some people aim to change fundamentals, focusing on the big picture in order to overcome baseline causes of vulnerabilities. Discrimination, poverty, inequity, and incompetence feed into disasters.

Others prefer to work on smaller scales and less ambitious steps. They demonstrate more direct, more tangible, and more immediate positive impacts, which they hope, in the end, might scale up to wider, deeper changes. Examples are managing forests to permit small wildfires and retrofitting properties to withstand earthquakes, all while changing our behaviour so that we can withstand wildfires and earthquakes without harm.

One approach never precludes the other. We can practice both together, so that they complement rather than impede each other. After all, chronic human conditions of vulnerability that cause disasters are ever-present, and must be tackled, at all scales, especially over the long term. This means that disasters never manifest rapidly. Rather than an event, we should recognize that a disaster is a long-term process.

Some hazards release their forces and energies swiftly with little specific warning. While we know broadly where earthquakes could strike at any time, such as Haiti and Jamaica, we cannot yet predict that an earthquake will occur in a specific place at a specific time. We know broadly where hurricanes could strike, also including Haiti and Jamaica, and we can observe the progress of a specific hurricane, but we cannot predict beyond a few days in advance when and where a major storm might make landfall. We know that Haiti and Jamaica are vulnerable to earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunamis, epidemics, and many other hazards because of their long-term social inequities and infrastructure inadequacies.

Consequently, in the same way that disasters are not natural, they are not unusual or extreme. They dramatically expose the vulnerabilities with which people live, and are typically forced by others to live, on a daily basis.

We can prevent 'natural disasters' and their human suffering, despite the presence of major environmental hazards, by reducing vulnerabilities. We must actively choose to do so.

Ilan Kelman is Professor of Disasters and Health at University College London, England and a Professor II at the University of Agder, Kristiansand, Norway.

This is an adapted excerpt from Disaster by Choice by Ilan Kelman, published by Oxford University Press on May 1, available in hardback and eBook formats.

Banner photo: Texas National Guard soldiers arrive in Houston, Texas, to aid citizens in heavily flooded areas from the storms of Hurricane Harvey. (Credit: The National Guard)