Science’s fallen hero

Meet Thomas Midgley, Jr., who solved science problems by making bigger ones.

Scientists take a drubbing in popular culture.

They're depicted as oddballs, like the dweebs in the Big Bang Theory, a ratings topper from 2007 to 2019 and now ubiquitous in lucrative, syndicated reruns. In the 1960's, Gilligan's Island featured "The Professor," an egghead with no social skills. And lest we think this is a relatively recent stereotype, Mary Shelley introduced the world to the mad, obsessive Victor Frankenstein in 1818.

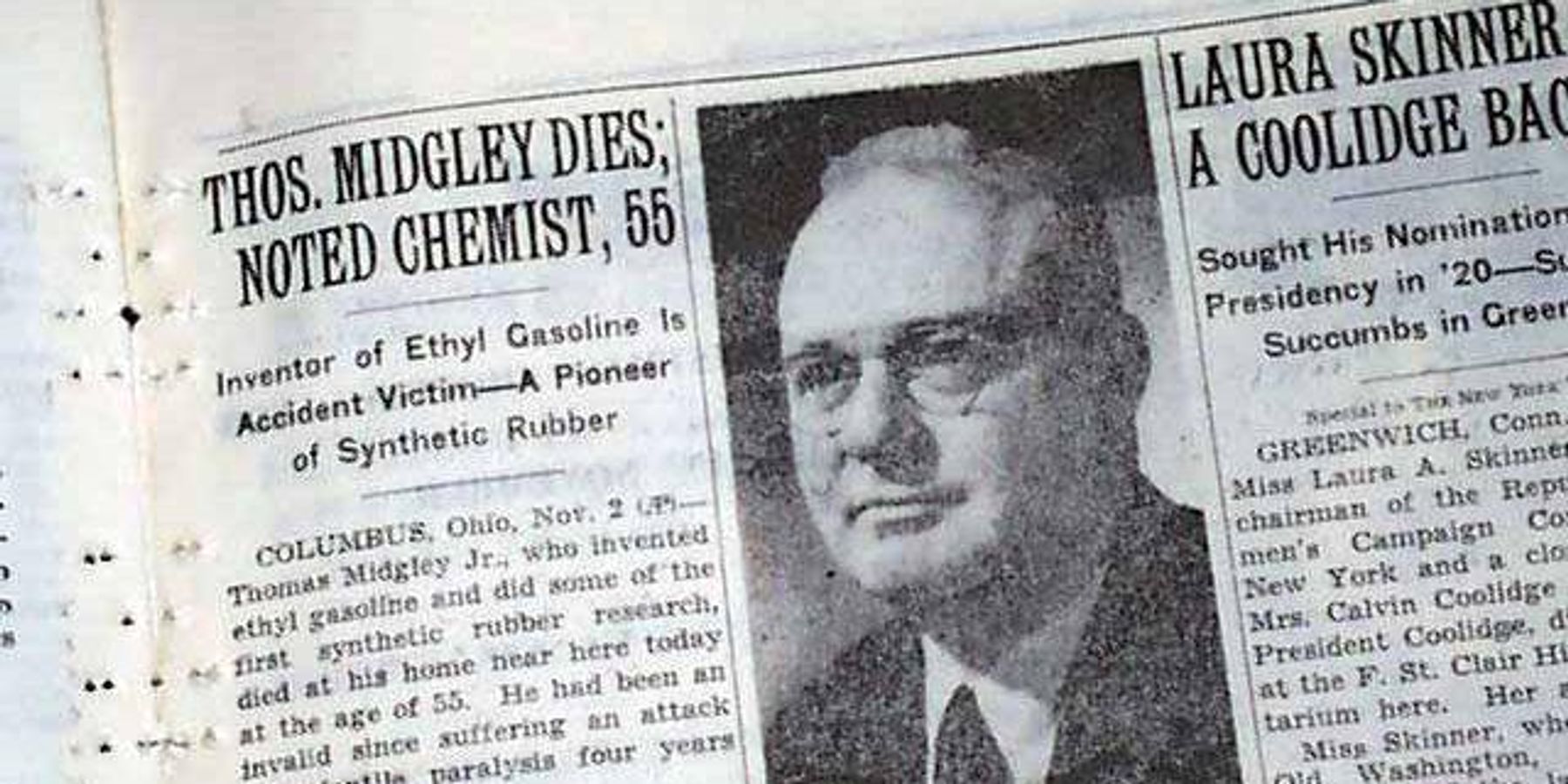

Enter Thomas Midgley, Jr., engineer and chemist who reached the scientist's equivalent of rockstar status nearly 100 years ago. Midgley, whose father and grandfather were both patent-holding inventors, was born in western Pennsylvania in 1889. After a boyhood in Columbus, Ohio, he took off for the Ivy League, emerging from Cornell with a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering in 1911.

Described as affable, Midgley is said by historians to have been in constant possession of a copy of the Periodic Table of Elements. By 1916, he was working in a General Motors lab assigned to develop a gasoline additive that would control "knocking" -- the pinging, rattling noises that can afflict an accelerating gasoline engine. By the early 1920's, Midgley's team had settled on tetraethyl lead (TEL) as the solution. The American Chemical Society (ACS) recognized Midgley with its annual Nichols Medal in 1923. He took the next month off with symptoms of lead poisoning. By contrast, GM stayed safe, marketing tetraethyl lead gasoline as "ethyl."

While evidence built on lead's impact on the human nervous system, especially for children whose brains were still developing, leaded gasoline was used for the next 50 years.

Harmful invention #2: Freon

But soon, Midgley had a different passion. GM's new appliance division Frigidaire, needed to find a safe, non-toxic refrigerant chemical to replace the toxic mash already in use. Combining fluorine and carbon, he hit paydirt: Dichlorodifluoromethane, better known by its marketing name, freon. Midgley was credited with developing an entirely new chemical family, chlorofluorocarbons (CFC's).

Midgley won the Priestley Medal -- the highest in ACS — in 1941. That same year, he became the organization's president.

By 1985, the ozone half of Midgley's star status began to fade. Scientists had detected "holes" in the Earth's stratospheric ozone layers at both poles, with Antarctica's situation particularly dire. At ground level, ozone is a pollutant — a primary component of "smog." But in the upper atmosphere ozone is a protectant—blocking skin cancer-causing solar radiation. Researchers tracked much of the problem to chlorofluorocarbons — notably Midgley's freon.

One final, fatal invention

Time-lapse photo from Sept. 9, 2019—scientists release these balloon-borne sensors to measure the thickness of the protective ozone layer high up in the atmosphere. (Credits: Robert Schwarz/University of Minnesota)

The world's nations responded with unusual urgency. By 1988, the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer took effect, outlawing the manufacture of CFC's. More than 180 nations signed on, with enthusiastic support from such notorious non-treehuggers as Ronald Reagan and UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Today, scientists tell us that damage to the ozone layer has begun to reverse, with projections that the ozone layer will be whole by the start of the next century.

Similarly, use of tetraethyl lead in gasoline is sharply down, but not completely out. A few nations including Algeria, Iraq, Myanmar and North Korea may still allow its limited use. The U.S. still allows leaded fuel for small aircraft, farm and lawn equipment. Neurologists credit the near-absence of TEL with health and intelligence improvements in children.

Wouldn't it be nice if blunders like Midgley's could be as easily reversed with climate change or COVID?

In the cruelest of ironies, Midgley's final invention directly caused his demise. In 1940, he contracted polio, leaving him a paraplegic but not dampening his zeal for invention. He devised a rope-and-pulley system to haul himself into a wheelchair and back into bed.

On November 2, 1944, Thomas Midgley, Jr. died in his Ohio home, inadvertently strangled by his own invention.

Peter Dykstra is our weekend editor and columnist. What are your favorite (or least favorite!) environmental songs? Send them in to Peter at pdykstra@ehn.org or @pdykstra.

His views do not necessarily represent those of Environmental Health News, The Daily Climate, or publisher, Environmental Health Sciences.