impaired_conception

Male infertility crisis in US has experts baffled.

The sudden rise in male infertility is a scary national crisis, and we can't blame it on Trump—or can we?

Hagai Levine doesn’t scare easily. The Hebrew University public health researcher is the former chief epidemiologist for the Israel Defense Forces, which means he’s acquainted with danger and risk in a way most of his academic counterparts aren’t. So when he raises doubts about the future of the human race, it’s worth listening. Together with Shanna Swan, a professor of environmental medicine and public health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Levine authored a major new analysis that tracked male sperm levels over the past few decades, and what he found frightened him. “Reproduction may be the most important function of any species,” says Levine. “Something is very wrong with men.”

That’s something you may not be used to hearing. It may take a man and a woman—or at least a sperm and an egg—to form new life, but it is women who bear the medical and psychological burden of trying to get—and stay—pregnant. It is women whose lifestyle choices are endlessly dissected for their supposed impact on fertility, and women who hear the ominous tick of the biological clock. Women are bombarded with countless fertility diets, special fertility-boosting yoga practices and all the fertility apps they can fit on their phone. They are the targets of a fertility industry expected to be valued at more than $21 billion globally by 2020. Even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention fixates on women, tracking infertility in the U.S. by tallying the number of supposedly infertile women. “It is as if the entire medical realm is shaped to cater to women’s infertility and women’s bodies,” says Liberty Barnes, a sociologist and the author of Conceiving Masculinity: Male Infertility, Medicine, and Identity. “For men, there’s just nothing there.”

That absence might be understandable if women were solely responsible for the success or failure of a pregnancy. But they’re not. According to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, the male partner is either the sole or contributing cause in about 40 percent of cases of infertility. Past infections, medical conditions, hormonal imbalances and more can all cause what is known as male factor infertility. Men even have their own version of a biological clock. Beginning around their mid-30s, male fertility gradually degrades, and while most men produce sperm to their dying day, those past 40 who help conceive have a greater risk of passing on genetic abnormalities to their children, including autism. “Men are a huge part of this problem,” says Barbara Collura, the president and CEO of Resolve: the National Infertility Association.

MOST READ

Startling new evidence suggests male infertility may be much worse than it appears. According to Levine and Swan’s work, sperm levels—the most important measurement of male fertility—are declining throughout much of the world, including the U.S. The report, published in late July, reviewed thousands of studies and concluded that sperm concentration had fallen by 59.3 percent among men in Western countries between 1973 and 2011. Four decades ago, the average Western man had a sperm concentration of 99 million per milliliter. By 2011, that had fallen to 47.1 million. The plummet is alarming because sperm concentrations below 40 million per milliliter are considered below normal and can impair fertility. (The researchers found no significant declines for non-Western men, in part because of a lack of quality data, though other studies have found major drops in countries like China and Japan.) And the decline has grown steeper in recent years, which means that the crisis is deepening. “This is pretty scary,” says Swan, who has long studied reproductive health. “I think we should be very concerned about this trend.”

Although there have reports of declining sperm counts before, they were easy to ignore. Research on sperm levels has been spotty, using different methodologies and drawing from varying groups, making it difficult to know that the declines some scientists observed were real, and not a function of miscounting. Skeptics of the latest conclusions countered that the new report was a study of many studies—it could only be as good as the work from which it drew. And even if the conclusions of the meta-analysis are accurate, the average sperm count still leaves most men on the normal side of fertile. Just barely.Yet fertility rates—the number of live births per woman—have drastically declined in the same countries with falling sperm counts. That includes the U.S., where fertility rates hit a record low this year, and where women are no longer bearing enough children to replace the existing population. Women need to average roughly 2.1 children—enough to replace themselves and their partner, with a spare bit to offset kids who don’t survive to reproductive age—to keep a country’s population stable through birth alone. The U.S. is at 1.8 and dependent on continued immigration to keep the population growing. Sociological and economic factors play a role in the changing size of the American family. Fertility rates were above the replacement level until the 2007 recession, then they plunged. And despite a years-long economic recovery and low unemployment, they’re still falling. Pair that with studies showing that nearly one in six couples in the U.S. trying to get pregnant can’t do so over the course of a year of unprotected sex—the medical definition of infertility—and it’s clear that something beyond economic insecurity is preventing Americans from having as many babies as they want. “When I see birth rates going down, I worry as a fertility doctor that men’s sperm counts are declining,” says Harry Fisch, a urologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York.

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTER

SIGN UP

Update your preferences »

This would seem to be the moment for the medical world to throw everything it can at understanding what is happening to male fertility. Yet researchers on male reproduction are forced to rely on less-than-perfect data because the kind of comprehensive, longitudinal studies that might conclusively tell us what is happening to sperm counts have never been done. The irony is that the medical establishment has been accused—with reason—of ignoring the particular needs of women over the years, yet in reproduction it is men whose problems are poorly studied and often misunderstood. Some experts even wonder whether an unconscious desire to ignore threats to male fertility may be tied up in fears over the future of masculinity itself. “Here is direct evidence that that function of reproduction is failing,” says Michael Eisenberg, a urologist and an associate professor at Stanford University, referring to the latest sperm-level research. “We should try to figure out why that is.”What we do know about declining sperm counts tells us a great deal about not only reproduction but also the overall health of men—and what it tells us isn’t good. Young men may think themselves invincible, but the male reproductive system is a surprisingly temperamental machine. Obesity, inactivity, smoking—your basic poor modern lifestyle choices—can dramatically reduce sperm counts, as can exposure to some environmental toxins. Low sperm counts may presage a premature death, even among men in the prime of their lives who might seem otherwise healthy. “Sperm count decline is the canary in the coal mine,” says Levine. “There is something very wrong in the environment.” Which means there may be something very wrong with men.

Why Johnny Can’t BreedThe study of sperm has always been murky. In 1677, the Dutch draper and amateur scientist Antony van Leeuwenhoek collected his semen immediately after having sex with his wife, examined it under a microscope of his own creation and saw millions of wriggling, tiny “animalcules” swimming in the seminal fluid. The Dutchman was the first person to observe human sperm cells, though he insisted that the sperm alone made an embryo that was merely nourished by the female egg and ovaries. Van Leeuwenhoek was simply following the example of classical thinkers like Aristotle, who believed female partners at most provided a fertile bed of soil in which the seed provided by a man could germinate and flower into a child. It wouldn’t be until the 19th century that the true roles of the sperm and the egg were finally sorted out.All those wriggling “swimmers” van Leeuwenhoek saw are what you would see if you magnified the sample of a healthy fertile man. A sperm cell is built for one thing: motion. Its torpedo-like head is a nugget of DNA containing the 23 chromosomes the male partner contributes to his future child, connected to a long tail or flagellum that propels the sperm to the egg, all running on the cellular rocket fuel of fructose, which is in the semen. Most sperm will never come close to an egg—while a fertile man ejaculates 20 million to 300 million sperm per milliliter of semen, only a few dozen might reach their destination, and only one can drill through the egg’s membrane and achieve conception. The chemical makeup of the vagina is actively hostile to sperm, which can only survive because semen contains alkaline substances that offset the acidic environment. That’s the paradox of sperm counts—although one healthy sperm is enough to make a baby, it takes tens of millions of sperm to beat the odds, which means that significant declines in sperm counts will eventually degrade overall male fertility. Notes Swan: “Even a relatively small change in the mean sperm count has a big impact on the percentage of men who will be classified as infertile or subfertile”—meaning a reduced level of fertility that makes it harder to conceive.

The fears about male infertility go beyond the stuff of dry science. “It’s the virility and fertility dilemma,” says Sharon Covington, an infertility therapist in Maryland. “How a man sees himself, and how the world sees him as a man, is often tied to his ability to impregnate a woman.” So perhaps it’s not surprising that the argument over how much sperm counts are declining—if they are declining—has been less a courteous scientific debate than a ferocious battle that has gone on for more than two decades.

This war began in Denmark, in 1990, when Danish pediatric endocrinologist Niels Skakkebaek began looking into male reproductive health. For years, he had been troubled by the rise in testicular cancer, as well as an increase in the number of boys with malformed testes. He thought assessing sperm quality and quantity might give him a clue to what was happening to his patients.

In 1992, Skakkebaek and colleagues reviewed all the published studies of sperm counts from around the world. (Sperm counts are done by tallying the number of sperm cells in one microliter of semen and then multiplying by 10,000 to estimate the total sperm in a milliliter—not dissimilar from the way police try to estimate the size of a large crowd from a geographic sample.) They calculated that the average sperm count in 1940 was about 113 million per milliliter of semen, and that by 1990 it had fallen to 66 million. In addition, they saw a threefold increase in the number of men with a sperm count below 20 million, the point at which infertility becomes a serious risk.Skakkebaek’s 1992 paper raised concern about the ability of the human species to continue reproducing itself, but skeptics immediately attacked, questioning the reliability of the original sperm studies the analysis was based on. The studies drew from very different groups of men of varying age and fertility. (Sperm count tends to decline with age, and men who gave a semen sample in a visit to a fertility clinic can reasonably be expected to have a lower count than, say, healthy men selected as donors for a sperm bank.) Some scientists believe older and less precise techniques for sperm counting may have artificially inflated the sperm levels of our fathers and grandfathers, which would make the drop to current counts appear steeper than it is.That’s why the new meta-analysis is so important. Swan, Levine and their international colleagues carefully sorted through more than 7,500 peer-reviewed papers before narrowing their search to 185 papers involving 43,000 men from around the world. By excluding studies before 1973, they cut out some of the less reliable older measurements, and they discarded any studies of men with known fertility complications or who were smokers, since smoking lowers sperm count. It’s not perfect—no meta-analysis is—but this evidence is the best we currently have, and the conclusions are disturbing. “The community is coming around on this,” says Eisenberg. “There have been some good counterarguments about sperm-level decline, but this paper really puts a lot of those arguments to bed.”Environmental CastrationProving that sperm levels are dropping has been difficult enough, and teasing out the cause is even tougher. Obesity, which has risen dramatically in Western countries while sperm counts have supposedly dropped, is linked to poor semen quality, as is physical inactivity. A 2013 study of American college students found that men who exercised more than 15 hours a week had sperm counts 73 percent higher than men who exercised less than five hours a week. And men who watched 20 or more hours of TV a week had much lower sperm counts than those who watched little to no TV. Stress is also a risk factor, as is alcohol use, which is on an upswing in the U.S., and drug use, which is increasing thanks to the opioid epidemic. Some scientists have theorized that electromagnetic fields from devices like cellphones could degrade semen quality, leading to weak and immobile sperm. Even heat can play a role. We know for certain that high temperatures can kill sperm, which is why the testicles are outside the body, keeping them up to 5.4 degrees cooler. Researchers know that birth rates decline nine months after a heat wave, leading some infertility experts to believe that climate change may actually be a factor in sperm count decline.Age also matters. In a recent study, Laura Dodge of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center looked at thousands of attempts at in vitro fertilization (IVF) performed in the Boston area and tried to gauge the impact of both male and female age on success. Female age remained the dominant factor, but male age factored in as well—women under the age of 30 with a male partner between 40 and 42 were significantly less likely to give birth than those whose male partner was between 30 and 35. That dovetails with other research showing that as men age, their sperm suffers increasing numbers of mutations, which in turn can make it slightly more likely that their children will be born with disorders like autism and schizophrenia. Older mothers may get the blame for infertility, but a new study found that new fathers in the U.S. are on average nearly four years older than they were in 1972, while almost 9 percent of new American fathers are over 40, double the percentage from 45 years ago. “We tell men that age is not an issue, but now we know that the male biological clock is real,” says Fisch.So is it simply modern life itself—obesity, inactivity, stress, cellphones, even older parenthood—that’s driving down sperm levels? It’s the beginning of an answer, but not the full one. Tobacco use definitely hurts sperm counts, yet smoking has fallen significantly in the U.S. That’s one reason a growing band of researchers have come to suspect the influence of toxins in the environment—specifically, endocrine-disrupting chemicals found in compounds like bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates.The theory is straightforward enough: These chemicals mimic the effect of the feminizing hormone estrogen and can interfere with masculinizing hormones like testosterone. The chemicals, which are found in many plastics throughout the environment, may be rewiring the sensitive male reproductive system, eroding sperm quality and quantity and even contributing to the sort of testicular disorders that first alarmed Skakkebaek years ago. The production of sperm is tightly regulated by the body’s hormones, and so any interference with those hormones—say, through exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals—could make itself felt first through damage to sperm quantity or quality. “You could still have sperm, but [levels] might be significantly lower than your father’s,” says Germaine Louis, the director and senior investigator at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.Most of the evidence for how these chemicals affect sperm comes from animal studies. A 2011 study found that mice who received daily BPA injections had lower sperm counts and testosterone levels than mice who received saline injections. A startling study from 2016 of fish in U.S. wildlife refuges in the Northeast found that 60 to 100 percent of all the male smallmouth bass studied had eggs growing in their testes—a startling feminization—which researchers linked to endocrine disrupters in the waters. Other studies have shown that phthalates appear to disrupt the masculinization of young lab rats. Animal models aren’t perfect, but as University of Texas toxicologist Andrea Gore notes, “the biology of reproduction is incredibly similar in all mammals. We are all vertebrates, and we have the same reproductive organs and processes that develop similarly with the same hormones.”Scientists can’t expose humans to endocrine disrupters in a controlled experiment, but some recent research has found associations between exposure to BPA and phthalates in the world, and declining sperm counts and male infertility in adults. A 2010 study of Chinese factory workers by De-Kun Li at Kaiser Permanente found that increasing levels of BPA in urine were significantly linked with decreased sperm count and quality, even among men who were exposed to levels of BPA comparable to men in the general American population. Another study from 2014 followed about 500 couples trying to conceive and found that phthalate exposure among men was tied to reduced fertility. These findings are all associations, which means that while exposure to endocrine disrupters is more likely to be found in men suffering from reduced fertility, it doesn’t mean that the chemicals themselves are definitively the cause. But the studies are stacking up. “For some of the endocrine disrupters like phthalates, the basic evidence is strong that they affect reproductive health,” says Louis, who carried out the phthalates study.Even more concerning, but harder to prove, is the damage endocrine disrupters may be doing in utero. As a fetus develops in a mother’s uterus, it is barraged by hormones and other chemicals that sculpt development. That includes the male reproductive system—testicles are formed in the womb, and although sperm levels can be altered in adulthood, they seem to be largely set before a boy is born. That means we could see sperm levels continue to decline for years, as boys who were exposed to endocrine disrupters before birth reach reproductive age and run into problems trying to have children of their own. “This trend hasn’t turned around, and it’s not going to turn around on its own,” says Swan, who has been studying the effects of endocrine disrupters for decades. “We don’t have a lot of time to lose.”The Baby Un-BoomIf this is a crisis, why is the medical establishment still arguing over the accuracy of statistical methods that approximate sperm levels from a variety pack of studies? Trying to figure out what is happening to sperm levels isn’t like trying to create an HIV vaccine. Researchers could follow a cohort of representative men from early adulthood through their reproductive years, taking regular semen samples under the same conditions and tracking lifestyle and environmental factors, including exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Such long-term studies aren’t easy or cheap, but somehow we’ve managed to pull them off for certain illnesses, like cardiovascular disease and cancer. The future of the human race—whether it has one—would seem to qualify as an important topic to explore in depth. “Why are we messing about with this?” says professor Allan Pacey, a male fertility expert at the University of Sheffield. “Let’s just answer the question.”A major, comprehensive study of semen quality has never been funded, however. Doctors are reluctant to even ask men for semen samples, and most men seem reluctant to give one—even though, as Eisenberg wryly notes, “it’s a lot more pleasant for the patient than a blood draw.”

“Male infertility has been ignored for 30 years,” says Christopher Barratt, a professor of reproductive medicine at the University of Dundee in Scotland. “What we understand can be written on a postage stamp.”The average man knows much, much less. Few men could even name the medical specialty that covers male reproductive health—it’s urology—and fewer still have ever seen a urologist, given that there are fewer than 12,000 of them in the U.S., about one-third the number of OB-GYNs in the country. Aside from a few online forums, there are no real support systems for men with infertility issues. Many men lack basic knowledge about risk factors for infertility. A 2016 Canadian study found that men could identify only about 50 percent of the potential risks to sperm production, largely missing out on known threats like obesity and frequent bicycling. “Most men just assume that when they want to have children they’ll be able to,” says Phyllis Zelkowitz, the director of research at the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal and the lead author on the study. “But that isn’t the case for a certain number of people.”The continued ignorance of male infertility is, in its way, another form of male privilege. Pretending that pregnancy is almost entirely a female responsibility means that women are forced to carry the burden and the blame when it goes wrong, while men, who are just as vital to healthy conception, rarely worry about how their lifestyles impact their own fertility or their possible children. “Women will often be sent to invasive, expensive procedures for fertility before a sperm test is ever done,” says Resolve’s Collura.So men are getting off free while their female partners put themselves through painful and expensive fertility treatments. Well, not exactly. The constant production of new sperm cells makes semen highly sensitive to toxins and disease, making it an ideal surrogate for male health—“like blood pressure,” as Louis puts it—beyond what it might signal for fertility. Poor sperm levels and infertility are a clear sign that men’s health is failing. One 2015 study found that men diagnosed with infertility have a higher risk of developing health issues like heart disease, diabetes and alcohol abuse, while another connected infertility to cancer. “Semen quality isn’t just about a couple getting pregnant,” says Louis. “There is increasing evidence at the population level that men with diminished semen quality die earlier and have more chronic diseases. This is as important to health as any disease state.”That male reproductive health goes mostly ignored in the face of those concerns is a striking example of what Cynthia Daniels, a political scientist at Rutgers University and the author of Exposing Men: The Science and Politics of Male Reproduction , calls the “paradox of male privilege.” A society that values men over women would presumably pour money and resources into determining exactly what is happening to sperm counts and reproductive health. But that would risk confirming that men, who are socially conditioned to think of themselves as indestructible, are in fact vulnerable—and vulnerable in that part of themselves most vital to manhood. At a moment when other talismans of masculinity, like the ability to financially support a family, are under assault, acknowledging the risk to reproduction may feel even more threatening to men. “Recognizing the male reproductive health problem unravels the notion of who men are and how they achieve masculinity,” says Daniels. “It seems to be more important to protect our norms of masculinity and traditional gender relations than it is to address the real health needs of men.”

One way to accomplish that goal is to enable men to take responsibility for their reproductive health. That’s what Greg Sommer, the chief scientific officer of Sandstone Diagnostics, is trying to do with Trak, a kit men can use to evaluate their sperm levels. It’s one of several similar do-it-yourself sperm testing services that offer men the chance to assess their own fertility without stepping inside a doctor’s office. That approach is more than a mere convenience because men are significantly less likely to go to the doctor than women, especially men in their prime reproductive years, when their health is otherwise likely to be good.Real, substantive change is needed from the medical and funding communities to address the male infertility crisis. It may be true, as skeptics countered after the publication of Swan and Levine’s meta-analysis, that we’re a long way from declining sperm counts heralding the end of the human race, at least as portrayed in works of pop art like The Children of Men and The Handmaid’s Tale . Millions of men and women are having children every day—even if an increasing number need artificial help like IVF. Yet more and more countries find themselves unable to raise their fertility rates above the level needed to replace their population, leading one prominent demographer to prophesy that the world has already reached “peak child.”It’s difficult not to wonder and worry about what will come next. “It’s an inconvenient message, but the species is under threat, and that should be a wake-up call to all of us,” says Skakkebaek. “If this doesn’t change in a generation, it is going to be an enormously different society for our grandchildren and their children.”Assuming, of course, they can have them.

Arks of the Apocalypse.

All around the world, scientists are building repositories of everything from seeds to ice to mammal milk — racing to preserve a natural order that is fast disappearing.

Arks of the Apocalypse

All around the world, scientists are building repositories

of everything from seeds to ice to mammal milk — racing

to preserve a natural order that is fast disappearing.

Photographs by SPENCER LOWELL and TEXT BY MALIA WOLLANJULY 13, 2017

It was a freakishly warm evening last October when a maintenance worker first discovered the water — torrents of it, rushing into the entrance tunnel of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, a storage facility dug some 400 feet into the side of a mountain on a Norwegian island near the North Pole. A storm was dumping rain at a time of year when the temperature was usually well below freezing; because the water had short-circuited the electrical system, the electric pumps on site were useless. This subterranean safe house holds more than 5,000 species of essential food crops, including hundreds of thousands of varieties of wheat and rice. It was supposed to be an impenetrable, modern-day Noah’s ark for plants, a life raft against climate change and catastrophe. Local firefighters helped pump out the tunnel until the temperature dropped and the water froze. Townspeople from the village at the mountain’s base then brought their own shovels and axes and broke apart the ice sheet by hand.

A few Norwegian radio stations and newspapers reported the incident at the time, but it received little international attention until May, when it was becoming clear that President Trump was likely to pull the United States out of the Paris climate agreement. Suddenly the tidings from Svalbard were everywhere, in multiple languages, with headlines like “World’s ‘Doomsday’ Seed Vault Has Been Breached by Climate Change.” It didn’t matter that the flood happened seven months earlier, or that the seeds remained safe and dry. We had just lived through the third consecutive year of the highest global temperatures on record and the lowest levels of Arctic ice; vast swaths of permafrost were melting; scientists had recently announced that some 60 percent of primate species were threatened with extinction. All these facts felt like signposts to an increasingly hopeless future for the planet. And now, here was a minifable suggesting that our attempts to preserve even mere traces of the bounty around us might fall apart, too.

Continue reading the main story

RELATED COVERAGE

Inside the Svalbard Global Seed Vault MAY 24, 2017

Photo

Spitsbergen is the largest island in the Svalbard archipelago, halfway between mainland Norway and the North Pole. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

The seed vault is perhaps the best-known project in a growing global campaign to cache endangered phenomena for safekeeping. Fortunately — the leak snafu notwithstanding — scientists, governments and even private companies have become quite good over the last decade at these efforts to bank nature. The San Diego Zoo’s Frozen Zoo cryogenically preserves living cell cultures, sperm, eggs and embryos for some 1,000 species in liquid nitrogen. Inside the National Ice Core Laboratory, in Lakewood, Colo., a massive freezer contains roughly 62,000 feet’s worth of rods of ice from rapidly melting glaciers and ice sheets in Antarctica, Greenland and North America. The Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington maintains the world’s largest collection of frozen exotic-animal milk, from mammals large (orcas) and small (critically endangered fruit bats), in order to help researchers figure out how to nourish the most vulnerable members of any species: babies. An international project called Amphibian Ark engages in ex situ conservation by relocating amphibians, the most endangered class of animal, indoors for safekeeping and sperm collection.

It seems to be a human impulse to collect things just as they’re vanishing. During the Renaissance, wealthy merchants and aristocrats exhibited their personal compendiums of mastodon bones, fossils and all manner of dried, pickled and stuffed creatures in what were called cabinets of curiosity. Some anthropologists believe their discipline emerged when Europeans began to experience a sort of nostalgia for the native populations they had wiped out with their diseases and guns. That feeling sent them scurrying off to gather up ethnographies, dying languages and sometimes even living subjects. Zisis Kozlakidis, the president of the International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories, an organization that represents some 1,300 biobanks containing specimens like viruses and the reproductive cells of clouded leopards, told me a collecting rush is underway, which he likened to an international space race. “There is,” he said, “a very intense feeling that we’re losing biodiversity quicker than we can understand it.”

Continue reading the main story

Photo

The entrance to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

A growing consensus among scientists holds that we now live in the Anthropocene, an epoch defined by humanity’s impact on planetary ecosystems. We are responsible for the current die-off of species, not some asteroid or volcanic eruption. The changes go far beyond animal disappearance: We’ve altered the composition of the atmosphere, shifted the chemistry of the oceans. In mere decades we’ve managed to distort a biological, chemical and physical reality that was relatively constant for millenniums. And now, in the face of these unfathomable transformations, we are trying desperately to hang onto and preserve what remains. Academics have even taken to studying the psychology of this human response — one such book, for example, is titled “The Anthropology of Extinction: Essays on Culture and Species Death.” In certain ways, our environmental banks are cabinets of curiosity for the Anthropocene age, tributes to the fantastical magnificence of the world in this geologic moment just as that moment is passing.

Continue reading the main story

ADVERTISEMENT

Continue reading the main story

We build banks to better understand, but also perhaps to save, our disappearing world. The plan is to study these specimens now but also to deliver them to the future, when scientists will presumably be more advanced than we are, technologically — and hopefully smarter. Geneticists can already clone animals; breed genetic diversity back into species at the brink of extinction via in vitro fertilization; rewrite genomes; and fabricate synthetic DNA. Glaciologists reconstruct ancient climate and atmospheric patterns (and predict future ones) by studying molecules trapped in ice. Marine biologists grow threatened corals in underwater nurseries. Botanists recently sprouted a delicate, white-flowered plant from genetic material inside seeds buried by squirrels in the Siberian permafrost 32,000 years ago. What will we be capable of in 10,000 years, or even 100?

But the world, as always, is changing — and now we’re fomenting and accelerating that process in ways we don’t fully understand. The banks themselves are vulnerable to that change. All manner of things can go wrong: power outages, faulty backup generators, fires, floods, earthquakes, contamination, liquid-nitrogen shortages, war, theft, neglect. In early April, a freezer failure at a University of Alberta cold-storage facility allowed some 590 feet of ice cores to melt, turning tens of thousands of years of frozen clues about the earth’s climate into puddles that one glaciologist, surveying the sad aftermath, likened to a swimming-pool changing room. The associated data that indicates what’s in these vaults — the genomes, the origin stories — could be hacked, corrupted, lost or just formatted in such a way as to be inscrutable to those who might try to decipher it later. These are the kind of anxieties that Oliver Ryder, a director at the San Diego Zoo’s Global Institute for Conservation Research, turns over in his mind in the middle of the night. “It is not, ‘Is something bad going to happen?’” he told me. “Over time, bad things will happen. They always do.”

—

Svalbard Global Seed Vault, Spitsbergen Island, Norway

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

Deep under the rock and permafrost of Plataberget Mountain, researchers have amassed what they hope might serve as a backup copy of the world’s agricultural crops. Stacked inside cavernous, ice-crusted chambers, these seeds contain the genetic diversity necessary to breed new varieties able to withstand the vagaries of a changing climate.

This subterranean safe house can hold up to 2.25 billion seeds and currently contains some 5,000 species of essential food crops. The facility’s temperature is maintained at just below 0 degrees Farenheit, which is cold enough to keep seeds viable for decades, and perhaps even thousands of years.

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

On its shelves are 160,000 varieties of rice, like those seen here, as well as thousands of essential grains and legumes — including some from Syria, which will be used to re-establish food production there once the fighting stops.

—

Amphibian Ark, various locations

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

For the Amphibian Ark, an international collaboration among scientists at more than 180 research facilities in 32 countries, herpetologists breed and maintain what they call “captive insurance colonies” like this one at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo with the aim of saving amphibians from a global die-off so severe that many regard it as an “extinction crisis.” They intend to someday release the specimens back into the wild.

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

No one has seen a Panamanian golden frog in the wild since 2009; the species is among many being ravaged by the deadly chytrid fungus. The frog at left, at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo, was captured 15 years ago and is considered a “founder.” His offspring are helping to rebuild the species in captivity. On the right is a female, her abdomen swollen with eggs.

—

Coral Restoration Foundation, Florida Keys

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

The Coral Restoration Foundation sustains the world’s largest collection of ocean-nursery-raised corals, which in the wild are increasingly endangered by overfishing, agricultural runoff, warming water temperatures and ocean acidification. Located a few miles off the coast of Key Largo, Fla., more than 400 coral “trees” grow here in the Tavernier Coral Nursery, including five threatened species.

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

Having pioneered a method for growing coral on treelike structures made from PVC pipes, the foundation grows coral in an underwater nursery for six to nine months before the specimens are taken to the ocean, glued into place and used to repopulate faltering reefs.

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

Depending on the coral species, researchers might let a specimen grow to the size of a softball or a cantaloupe in the nursery before replanting it. Coral reefs are some of the richest ecosystems on the planet; despite being present on less than 2 percent of the ocean floor, they provide food and shelter to about a quarter of all known marine species.

—

National Lab for Genetic Resources Preservation, Fort Collins, Colo.

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

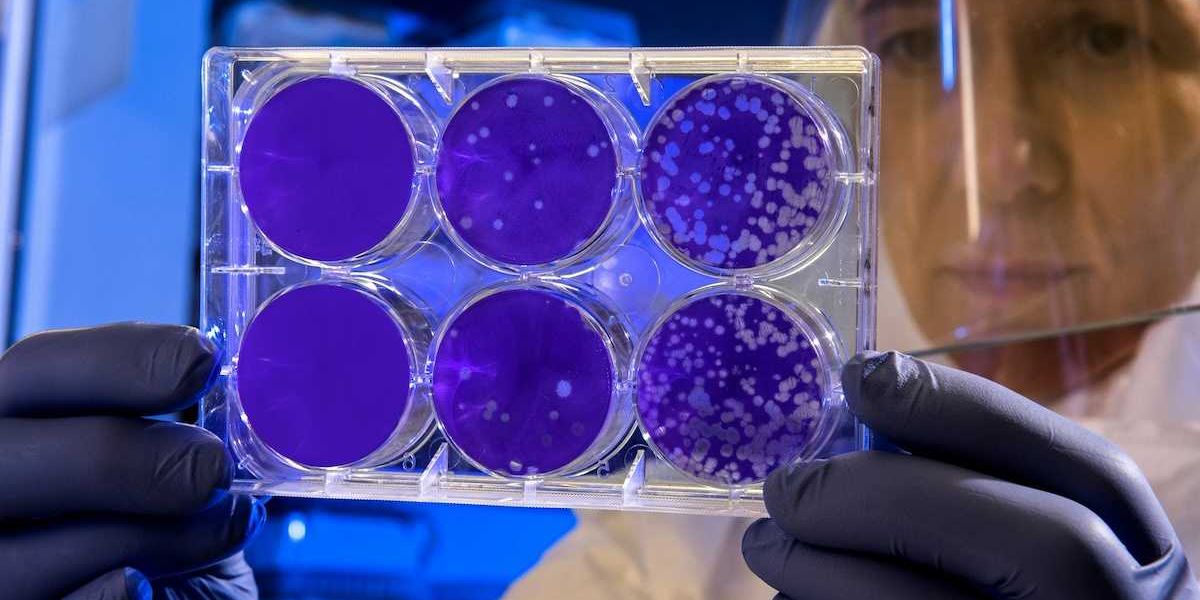

The National Lab for Genetic Resources Preservations in Fort Collins, Colo., is run by the Agricultural Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture. Here, a researcher checks cryogenically frozen coral sperm at the lab, where it is stored alongside other genetic samples. This summer, Smithsonian scientists will grow coral produced from cryopreserved and thawed sperm and, for the first time, transplant it into the wild.

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

Most corals are hermaphroditic; one way they reproduce is by releasing tiny, floating packets that contain both sperm and eggs. When reefs die off and become fragmented, it is harder for corals to reproduce naturally. Researchers preserve sex cells cryogenically for future breeding.

—

Exotic-Animal Milk Bank, Washington

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

The Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington stores 16,000 frozen samples of milk from approximately 180 species, making it the world’s largest collection of frozen exotic-animal milk in the world. Here, researchers milk a critically endangered Bornean orangutan named Batang. In addition to breast-feeding her infant, Redd, Batang permits regular milking for the milk bank.

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

Milk samples from a giant anteater, whose species has declined by 30 percent over the last 10 years. Milk is essential to the survival of mammals; along with basic nutrition, it contains hormones, microbes and molecules critical to immune function.

—

The Frozen Zoo, San Diego

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

A 10-foot-by-20-foot room inside the San Diego Zoo keeps the living cells of more than 1,000 species from around the world — the Hawaiian bird called the po‘ouli, which is believed to be extinct; the northern white rhino; the western lowland gorilla; the Somali wild ass — preserved in liquid nitrogen at minus 320 degrees. This is, says Oliver Ryder, the zoo’s director of conservation genetics, “the greatest density of vertebrate biodiversity anywhere in the galaxy.”

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

The living cells of Amani, a female southern white rhino about 9 years old. When thawed, the cells can be used to grow new rhino cells.

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

The living cells of Kamilah, a female western lowland gorilla, age 40, are also preserved in the Frozen Zoo.

—

U.S. National Ice Core Laboratory, Lakewood, Colo.

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

This 55,000-cubic-foot, minus-33-degree freezer holds some 62,000 feet of ice rods augured with machines out of ice sheets and glaciers. The study of air bubbles, dust and ash particles, isotopes, gases and organic materials frozen in the ice helps scientists understand past climates and predict future ones. The oldest ice stored in the lab is 417,000 years old and comes from Princess Elizabeth Land, Antarctica. Another core, 11,168 feet long and drilled from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, is an archive of atmospheric history going back 68,000 years. In a nearby decontaminated “clean room,” researchers bundled in winter coats and hats slice the cores, measure their electrical conductivity and analyze individual ice crystals using high-resolution macrophotography. To better understand long-ago climates, ice core scientists, engineers, and drillers from 24 countries are currently searching for a suitable site to drill a 1.5 million year old or older ice core.

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

The cross-section of an ice core at left is from the South Pole, taken from a depth of about 5,300 feet and estimated to be about 50,000 years old. The brown and gray layers of the processed ice core at right are bits of ash deposited by a volcanic eruption some 22,000 years ago.

Spencer Lowell is a photographer based in Los Angeles. He last photographed Mark Zuckerberg for a cover story about Facebook.

Malia Wollan is the Tip columnist for the magazine. Her last article was about the quest to make a naturally blue M&M.;

In vitro fertilization may save coral reefs.

Marine biologists at the California Academy of Sciences have joined a new international effort to rescue endangered coral reefs from the consequences of widespread human destruction and a warming climate.

Marine biologists at the California Academy of Sciences have joined a new international effort to rescue endangered coral reefs from the consequences of widespread human destruction and a warming climate.

Teams of research divers from the academy will set off this summer on expeditions to the Caribbean and Mexico, where they will seed two of the region’s major reefs with millions of coral larvae born from the organisms’ sperm and egg cells.

As colorful as flower bouquets, corals are actually colonies of tiny animals that build their limestone homes from the sea, and derive their colors from the algae that live inside them. Their lives are increasingly threatened by global plagues like expanding human development, ocean pollution, and the twin signals of global climate change: rising temperatures and increasing ocean acidification.

Recent record-shattering El Niños have raised Pacific Ocean temperatures and caused a new worldwide episode of coral bleaching that is turning the organisms dead white. The scourge began in 2014, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and is already the worst and longest bleaching episode in history.

Bart Shepherd, the director of the academy’s Steinhart Aquarium, and Luiz Rocha, the curator of ichthyology, will lead about 20 divers on a new experiment in coral reproduction.

“If it’s successful,” Shepherd said, “it opens the possibility for widespread application on coral reefs everywhere.”

Shepherd’s group has joined with leaders of an international research and conservation group called Secore International — Sexual Coral Reproduction — whose founder and president, Dirk Petersen, led the original research into a unique method of in vitro fertilization of coral organisms.

Five years ago, Petersen and researchers diving at the Caribbean Marine Biological Institute in Curacao, collected coral sperm and egg cells in the water while the corals were spawning, and reared the coral larvae in the laboratory. When they matured, the researchers transplanted the coral larvae onto small, fist-size tiles that the divers then transplanted to the degraded reef by the thousands.

The experiment was successful and within two years a high proportion of new corals were flourishing and growing, Petersen and his colleagues reported in the journal Global Ecology and Conservation.

“This is now actually a five-year plan, and eventually it could become a global restoration project for corals everywhere,” Petersen said during a recent visit to San Francisco, where he and Shepherd completed working on details of the academy team’s role this summer.

The expedition is scheduled for August because the corals spawn only about once a year, releasing their sex cells into the water by the millions, Shepherd explained. The event, he said, occurs only in August at night and only within a few days after a full moon.

It’s during those fleeting nights of spawning action that Shepherd and his colleagues from the academy will be diving to collect the coral gametes. Then, after they have become larvae in the Caribbean institute’s lab, the divers will return to seed the nearby reef with the fresh infant corals.

The researchers’ first two targets will be on the degraded reef at the institute’s field station in Curacao, and then on the Yucatan Peninsula, where the famed Great Maya Reef stretches more than 620 miles south to the coast of Belize.

The academy’s effort at coral midwifery is part of a $10 million commitment the institution has made specifically to research and restoration efforts on the world’s endangered reefs.

“We’re planning 20 new expeditions over the next five years to regions where coral reefs are threatened,” said Jonathan Foley, the academy’s executive director. “And our people will be putting boots on the ground for a rescue experiment that’s unique — not just for proving out a new technique to restore coral reefs, but for making the technique better.”

David Perlman is The San Francisco Chronicle’s science editor. Email: dperlman@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @daveperlman