From making it to managing it, plastic is a major contributor to climate change

New report finds plastic production and use could have the equivalent impact of nearly 300 new coal power plants on Earth's climate over the next decade.

Plastic is polluting oceans, freshwater lakes and rivers, food and us — but it's also a major contributor to global climate change, warns a new report.

Scientists, policymakers and consumers are increasingly aware of the threat plastic pollution poses to oceans and water, wildlife, food and people. However, often lost in calculating plastics' environmental harm is its contributions to climate change.

"I don't feel the petrochemical buildout is being considered as part of climate change discussions at any level in our state [Pennsylvania]," Michele Fetting, program manager at the Breathe Project, a coalition of 24 environmental organizations, told EHN.

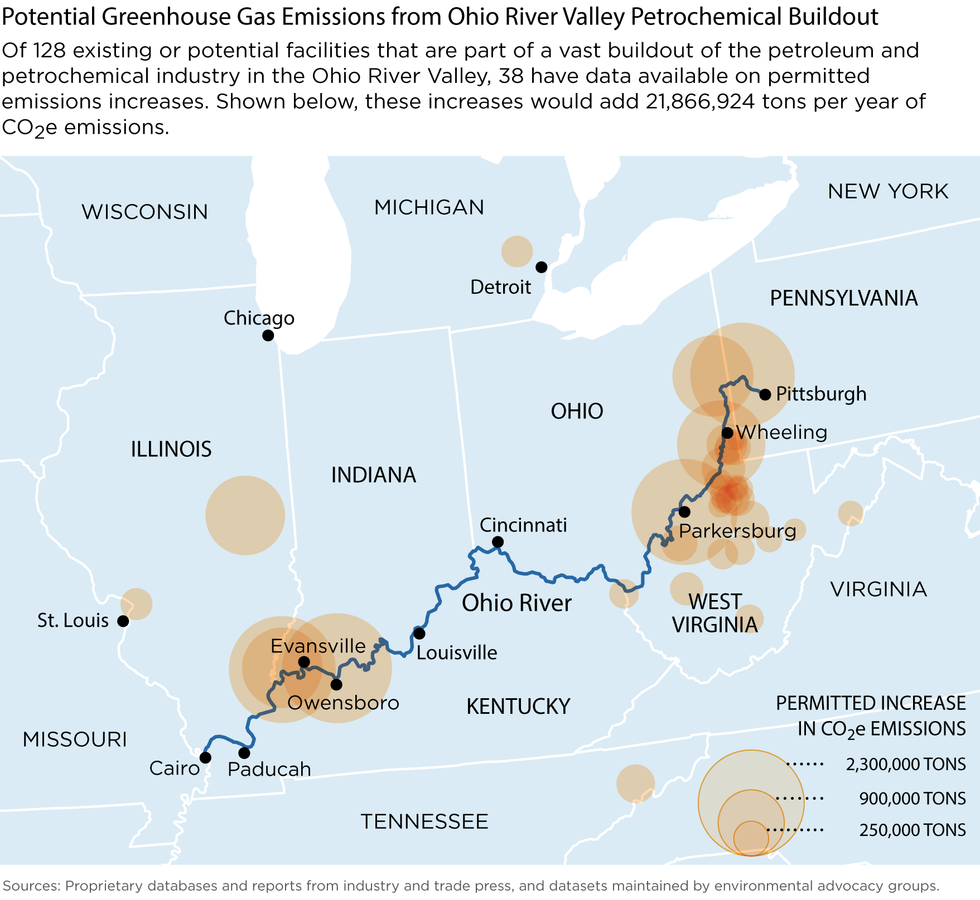

Petrochemical facilities, such as cracker plants, take fuels like natural gas and convert them to chemical products, which are most often used to make plastics. Shell is building a massive petrochemical complex in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, as part of a broader effort to put such facilities in multiple spots along the Ohio River Valley.

Each step in the life of a piece of plastic — production, transportation and managing waste — uses fossil fuels and emits greenhouse gases and, as petrochemical and plastic production continues to ramp up, these impacts must be considered, according to the report released today by the Center for International Environmental Law, the Environmental Integrity Project, FracTracker Alliance, the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, 5Gyres, and #BreakFreeFromPlastic.

The organizations say putting a stop to increases in petrochemical and plastic production "is a critical element in addressing the climate crisis."

"Nothing short of stopping the expansion of petrochemical and plastic production and keeping fossil fuels in the ground will create the surest and most effective reductions in the climate impacts from the plastic lifecycle," the authors wrote.

The report included stark numbers:

- In 2019, producing and incinerating plastic will emit an estimated 850 million metric tons of greenhouse gases, the equivalent of 189 coal-fired power plants.

- If production continues on the same trajectory, by 2030 plastic-related greenhouse gas emissions will reach 1.34 gigatons per year, which is roughly the emissions released by 295 coal plants.

- By 2050, the annual greenhouse gas emissions from plastics will reach an estimated 2.8 gigatons per year – the equivalent of about 615 coal plants.

Carroll Muffett, president & CEO of the Center for International Environmental Law, told EHN the report is "underestimating the climate impacts of plastics production."

"If you look, for instance, at fracking, there are uncalculated emissions with land disturbance, or shipment of water to fracking wells, or massive ongoing leakage from natural gas pipelines," he said. "All will dramatically increase with upstream feedstocks for plastics."

Entire lifecycle

The report calculates the climate costs of plastic by looking at each step in the life of plastic: extraction and transport of fossil fuels; refining and manufacturing; managing waste; and plastic pollution in the environment.

Fossil fuels are a critical component in producing plastic. Extraction and transport, the report estimates, contributed about 9.5 million to 10.5 million metric tons of greenhouse gases in 2015 — that's just in the U.S. Another estimated 108 million metric tons was emitted outside the U.S.

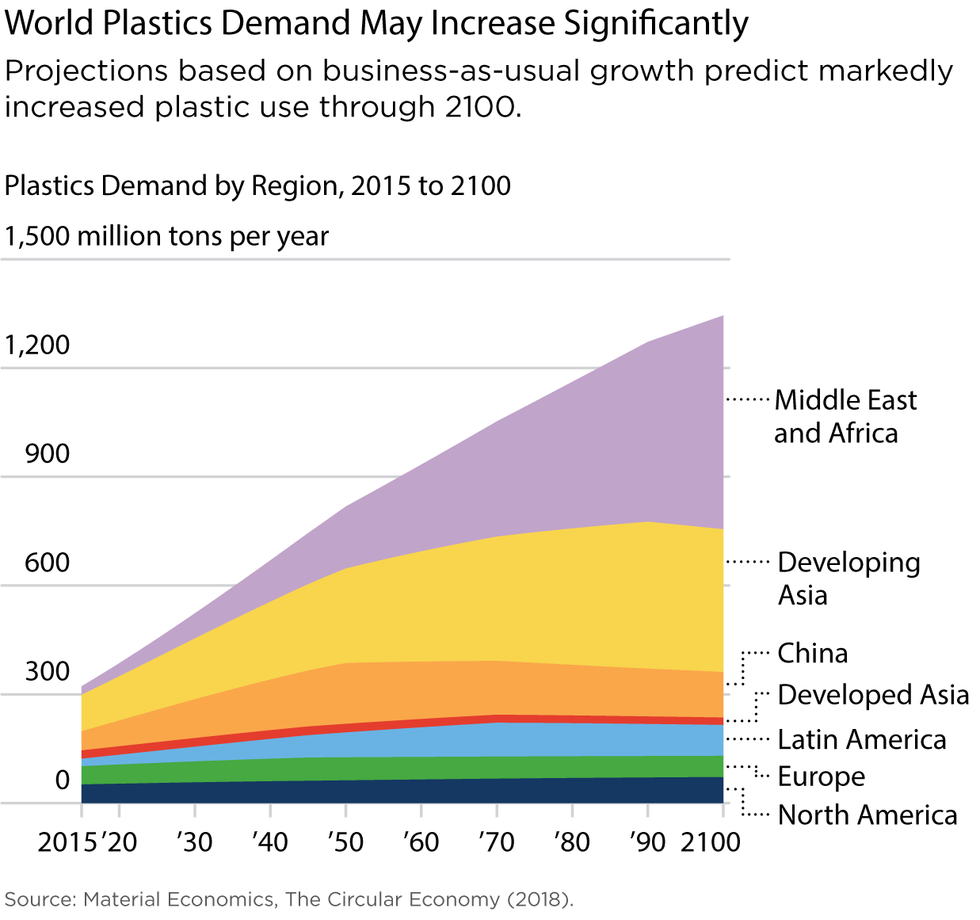

"If growth trends continue, plastic will account for 20 percent of global oil consumption by 2050," according to the report.

Globally, refining and manufacturing plastics contributed roughly 184 million to 213 million metric tons of greenhouse gases in 2015. This is the equivalent of about 45 million vehicles driven for a year.

Managing plastic waste, mostly via incineration, contributed about 16 million metric tons of greenhouse gases in 2015.

Curbing ocean carbon capacity

What about all that plastic that ends up in our oceans?

Scientists have yet to quantify the climate impact of such pollution, but nascent research suggests it may continually release greenhouse gases and could interfere with the "ocean's capacity to absorb and sequester carbon dioxide," the authors wrote.

This early research suggests microplastics are toxic to phytoplankton, which take carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and ocean water and produce carbohydrates via photosynthesis, and zooplankton — microscopic creatures that transport carbon deep into the ocean.

"Without this critical step in the process, the CO2 fixed by the phytoplankton would quickly re-enter the surface waters and the atmosphere," the authors of the new report wrote.

"This is deeply troubling," Muffett said. "There's potential that microplastics are interfering with climate not just by release methane, but by interfering with the ocean's ability to serve as natural carbon sink."

“The Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory of plastics”

Pennsylvania Governor Wolf tours the Shell Cracker Plant Site in Beaver County, PA. (Credit: Governor Tom Wolf)

Despite growing awareness of plastic pollution, there is an ongoing expansion of petrochemical and plastic production happening in the United States, as well as in China, the Middle East, Europe and South America.

In the fall of 2017, the American Chemistry Council estimated $164 billion in investment for 260 new or expanded petrochemical facilities in the U.S. Just one year later, that estimate was blown away — the Council reported investments of more than $200 billion in more than 330 new or bolstered facilities. "In the space of a year, both the planned investments and the number of new or expanded facilities grew by more than 25 percent," the new report said.

Muffett said to a "great extent the production of plastics is driven not by demand but by supply."

"Plastics' feedstock is 99 percent fossil fuels," he said. "Plastics are effectively a byproduct, taking what would be a waste stream from oil and gas. The fracking boom is resulting in a massive buildout of new infrastructure for plastics production."

Roughly 70 percent of petrochemicals in the U.S. become plastic resins, synthetic rubber, or fibers, Muffett and colleagues wrote in the new report.

A lot of the expanded production is centered around the Ohio River Valley, spanning from Pennsylvania to Illinois.

Fetting agrees that supply is driving the bolstered production. In Pennsylvania, there is "frack sand, cheap gas, water supplies and infrastructure," she said. "Industry sees this as the perfect location to build this … the Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory of plastics."

Fetting said local media has just recently caught on to the story that this buildout will forever alter the region. And, while direct human health impacts from emissions are a huge concern, she said nobody is talking about the climate change impacts.

"For every cracker plant built, we'll need to frack about a thousand wells every two to three years to provide feedstock. That's a lot of climate pollution," she said. "And we haven't heard any of our elected officials talk about this as part of a climate discussion."

The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates natural gas production in the Appalachian region will see an "increase of more than 350 percent from 2013 to 2040," according to the new report. "Production is projected to increase [more than]700 percent by 2023 compared to 2013 figures."

The region's petrochemical expansion will require an estimated 583 billion gallons of freshwater and 380 million tons of sand.

When it comes to the petrochemical expansion, at least in Pennsylvania communities, "people still don't understand what's happening," Fetting said.

But that's starting to change.

"When people see they're turning our region into another cancer alley, it makes people sit up and say 'what have we done?' 'What are we doing'?"

Shell did not return requests for comment on the new report.

Stopping single-use, reducing fossil fuels

The authors lay out a roadmap to reduce plastic's climate impact including: stop making and using single-use plastics; stopping the buildout of new oil, gas and petrochemical infrastructure; moving communities to zero-waste; forcing producers of plastic goods to accept responsibility for the environmental impacts; and putting in place more ambitious greenhouse gas reduction goals (that take plastic impacts into account.)

"The underlying drivers of climate change and the plastic crises are closely linked – so the solutions are closely linked," Muffett said. While some of the solutions may seem political nonstarters, he said tackling single use plastics and curbing fossil fuel use are a great first step.

"One of the best ways to respond to the plastics crisis is to keep fossil fuels in the ground in the first place," he said. "And the overwhelming proportion of plastics in our lives are unrequested and completely unavoidable."