Peter Dykstra: Leaving a hero’s footprint on Earth

Whether or not you've heard of my friend Steve Sawyer, here's how he touched your life.

Environmental heroes and villains have been around long enough to compile quite a history. One of the heroes died this week.

Since he was also one of the quietest of heroes, you may not know his name, but you certainly know his work.

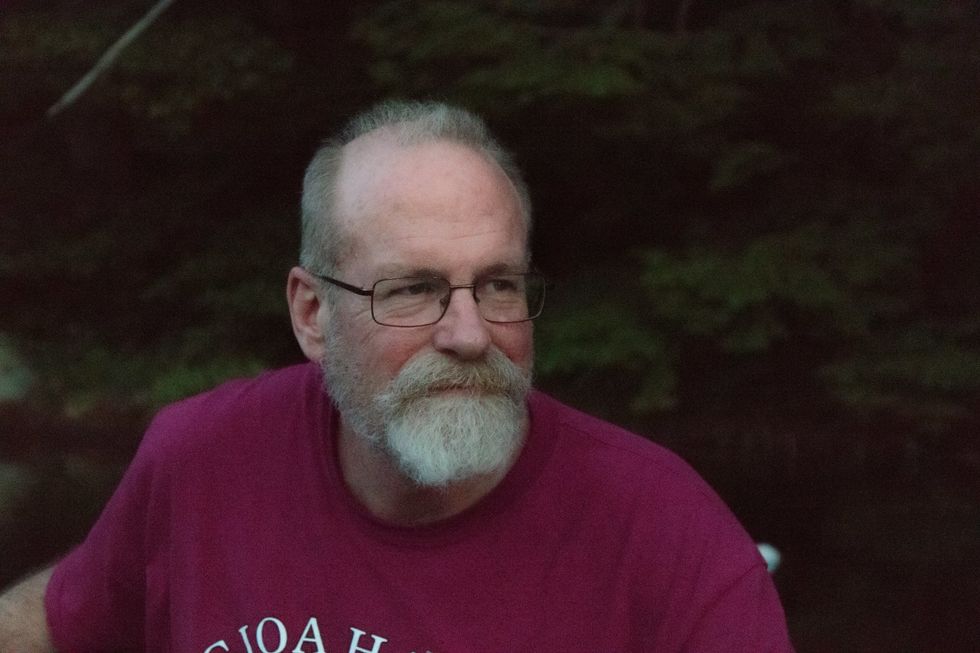

Steve Sawyer has been my friend for 40 years. We missed the early, Book-of-Genesis days of Greenpeace by several years but met when we both showed up as Greenpeace volunteers in its fledgling east coast outpost in Boston in late 1978.

I was mostly a house creature, helping the new office with fundraising, media, and other things that none of us had any experience with. Steve, on the other hand did everything and, with few exceptions, did it all better than anyone else -- politics, strategy, and, depending how you feel about Greenpeace, leading the way on either dynamic protests or drama queenery.

He was a laconic New Englander from rural Antrim, New Hampshire. He could lead a team or fix a creaky boat with the best of them. He could also crack a killer wry joke or bang out a superbly passable Eric Clapton or Mark Knopfler guitar riff.

In the 1980's, Sawyer crewed or led trips on the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior opposing a range of abuses from the ocean dumping of nuclear waste off Spain to Canada's massive hunt for harp seal pups to disposal of acid waste off the New Jersey shore.

In the Jersey campaign, we prepared to welcome Bruce Springsteen, the state's leading citizen, aboard the boat. Upon hearing about the possible visit, he borrowed one of The Boss's iconic lyrics, deadpanning, "well, he's not gonna strap his hands across my engines." Alas, Springsteen's visit never materialized, but the one-liner lives on.

He was a diplomat in an internal dispute that almost sunk the young organization in 1980; he supervised the overhaul of the rickety Rainbow Warrior, then led an expedition that was one of the proudest – and quietist – efforts in Greenpeace history.Rongelap rescue

Credit: Kelly Rigg

The Marshall Islands were the venue for many of the biggest U.S. nuclear weapons tests in the 1950's. A bomb at the Bikini Atoll test site left a nearby, inhabited island contaminated. The Americans evacuated the residents of Rongelap. Three years later, the U.S. pronounced Rongelap safe and returned its population from atomic exile.

But once back home, the Rongelapese suffered with thyroid cancer and other ills associated with radiation poisoning. Petitions to the U.S. to again evacuate Rongelap were rejected. In 1979, the U.S. acknowledged that Rongelap's native food supply was poisoned. The Rongelapese were treated to shipped-in food, but still no evacuation.

Sawyer and the Rainbow Warrior crew arrived at Rongelap in May 1985 in the midst of a 10,000-mile journey from the U.S. east coast to New Zealand, where the ship was to lead a protest voyage to France's Pacific nuclear weapons test later that summer.

The ship was ill-suited to move a village of 260 people, their buildings, livestock, and more, but the RW made four trips from Rongelap to Mejato, an uncontaminated atoll 100 miles away, to carry the Rongelapese to a safe new home.

In July of that year, the crew went ashore in Auckland, New Zealand to celebrate Sawyer's 29th birthday. An underwater explosion tore through the RW's hull. The ship's photographer Fernando Pereira dashed aboard to rescue his gear from the sinking ship when a second explosion trapped and drowned him. Two members of the DGSE, France's Secret Service, were arrested and convicted for the bombing and murder.

In the wake of the global furor caused by bombing, Sawyer first became leader of Greenpeace in the U.S., then the head of a global organization that was otherwise inclined to mistrust Americans. Sawyer displayed a gift for assembling a team full of people with seething contempt for authority in order to serve as their authority figure.

He left Greenpeace after three decades in 2007 in order to found and run the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC), a trade association that became a unifying body for a booming industry.

Lasting legacy

Sawyer and Kelly Rigg (Via Steve Sawyer's Facebook page)

But here's a useful digression to Sawyer's New England days. In 1984, a young Greenpeace activist, Kelly Rigg, exposed the U.S. Interior Department's blind zeal to sell offshore oil and gas leases. She bid on thousands of acres of Georges Bank off the New England Coast.

Only problem is, the oil companies saw little gain and high risk in exploring the historically rich fishing grounds. They stayed away, and Ronald Reagan's Interior Department abruptly cancelled the Greenpeace-only auction.

Years later, a Utah wilderness guide named Tim DeChristopher followed Rigg's example, shaming the GW Bush White House and the fossil fuel industry by outbidding Big Oil on 22,000 acres of western public lands. The Feds threw the book at DeChristopher, who served 21 months on Federal charges.

Happily, Kelly Rigg was only sentenced to a life with Steve Sawyer. She remains a consummate environmental activist based in Amsterdam. Steve and Kelly have two adult children, Layla and Sam, who retain their parents' smarts and resolve.

You may have noticed I'm writing about the late Steve Sawyer in the present tense—that's because his life's impact will be felt forever.

Farewell, friend.