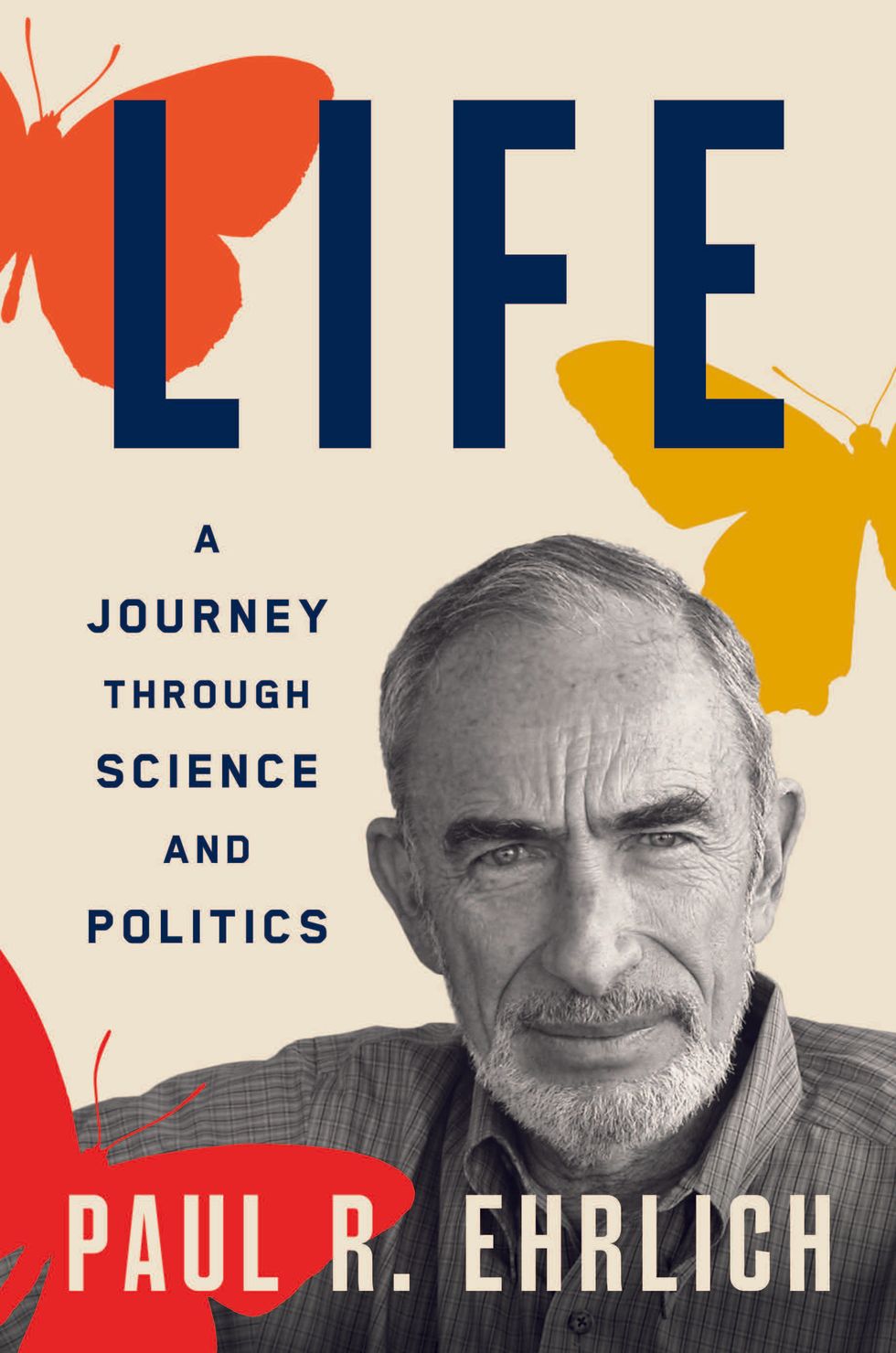

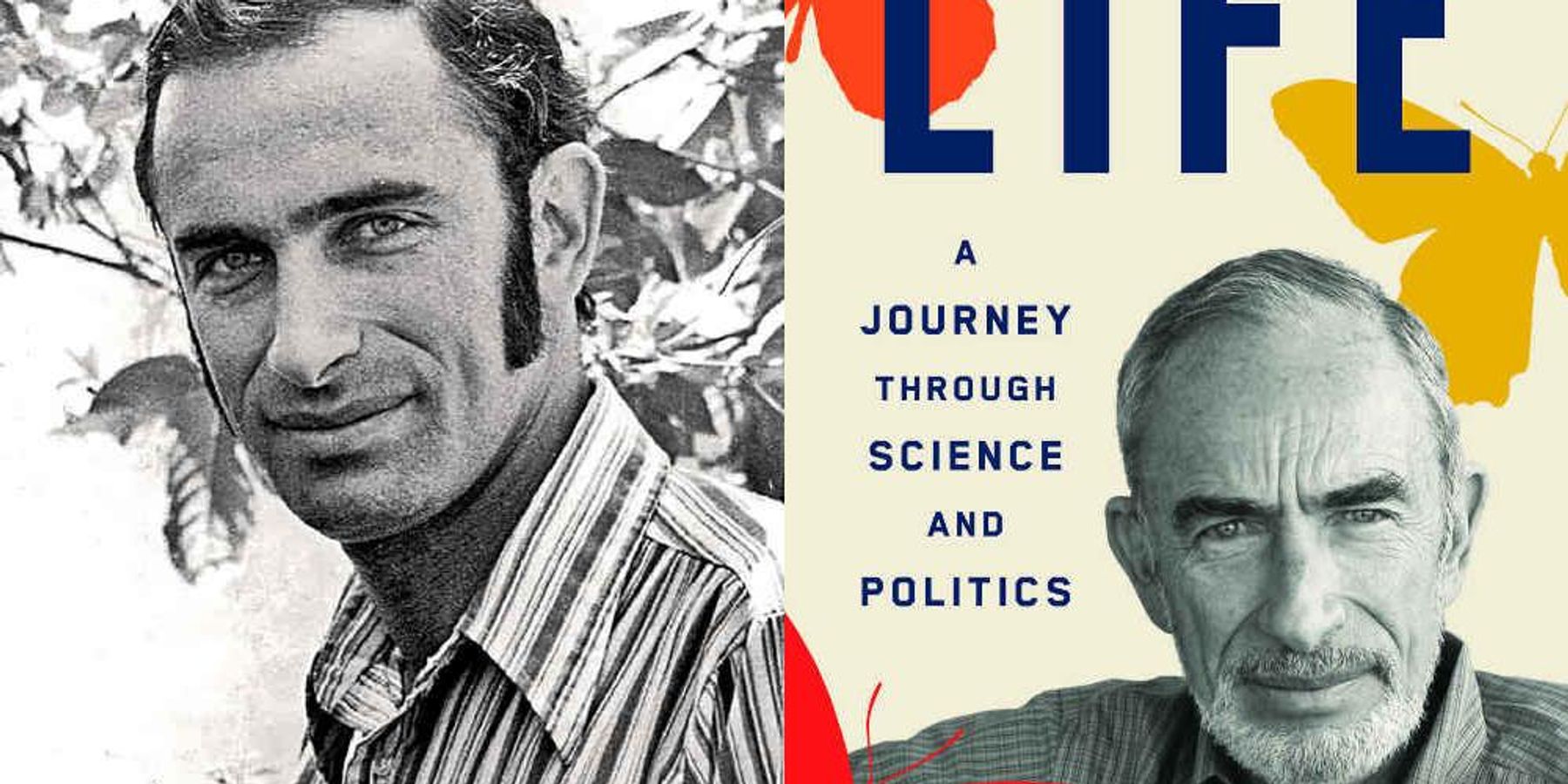

Paul Ehrlich: A journey through science and politics

In his new book, the famous scientist reflects on an unparalleled career on our fascinating, ever-changing planet.

As I’ve aged, I’ve found myself increasingly diverted from my great interest in human achievements in science to increasing distress at certain features of modern human culture that I believe threaten us all, and by all I mean the natural world, not just ourselves.

I, of course, have lived in an amazing time for a scientist. When I was first fooling around with butterflies, scientists knew nothing about DNA. We thought humanity’s prehistory was a pretty straight line from a chimplike ancestor, through Australopithecus, to Homo erectus, to Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. Only later did scientists uncover the great diversity of our ancestors and the evolutionary relatives with which they interacted. Doctors had just begun using catheters to diagnose problems in beating hearts, electron microscopes had just been developed, nuclear power and nuclear proliferation were still in the future, computers did not then control much of human activity as they do now, no artificial satellites were circling Earth, and no human being had ever ventured above the atmosphere.

That we now know so much more about how organisms function and evolve and how ecological systems work than was known when I caught that Euphydryas phaeton in Bethesda at the age of fifteen I find mind-boggling. At a more plebeian level, when I started at Stanford in 1959 we had no Xerox machines, no smartphones, no desktop computers, and, of course, no word processing and no email.

On the cultural front, as noted earlier, I might have been able to write a similar screed of social and political accomplishment for America if I were writing this in, say, 1980, before the Reagan presidency set us on the facilis descensus Averno.

In 1980 the situation of African Americans compared to twenty-five years earlier had improved greatly — lynchings had died out in the South, no facilities in Lawrence, Kansas, were still segregated, and increasing numbers of people were realizing that those with darker skins could be top scholars and excellent politicians. Women were well on their way to penetrating niches once reserved for men, and I had taken much of my instrument training from a female pilot.

People in religious minorities were infrequently at risk of violence.

Further, official notice of and action on environmental problems was, if inadequate, in existence and cheering, bolstered by some landmark legislation. Much of that was reversed by Reagan, and since Reagan, socioculturally it’s been at best a roller-coaster of destruction of environmental safeguards and social safety nets followed by the reinstitution of these safeguards, greater acknowledgment of the threat of fossil fuel – induced climate change, and attempts to increase access to affordable medical care and the like.

Nevertheless, inequality has continued to grow, and there has been a decline generally in American indirect democracy, epitomized by the nearly successful Trump putsch of January 6, 2021, a set of events virtually inconceivable a decade or more before. To cope with the crises of biodiversity loss, climate change, overpopulation, and threats to the provision of life’s essentials, far more is needed than scientific reports that are too often largely ignored.

To rescue the human enterprise in the long run requires strong action in the short run directed toward saving biodiversity and bringing the human enterprise within sustainable limits.

This is an excerpt from Life: A Journey Through Science and Politics by Paul R. Ehrlich is published by Yale University Press.

Banner photo credit: Left - Wikipedia Commons; Right - Yale University Press.