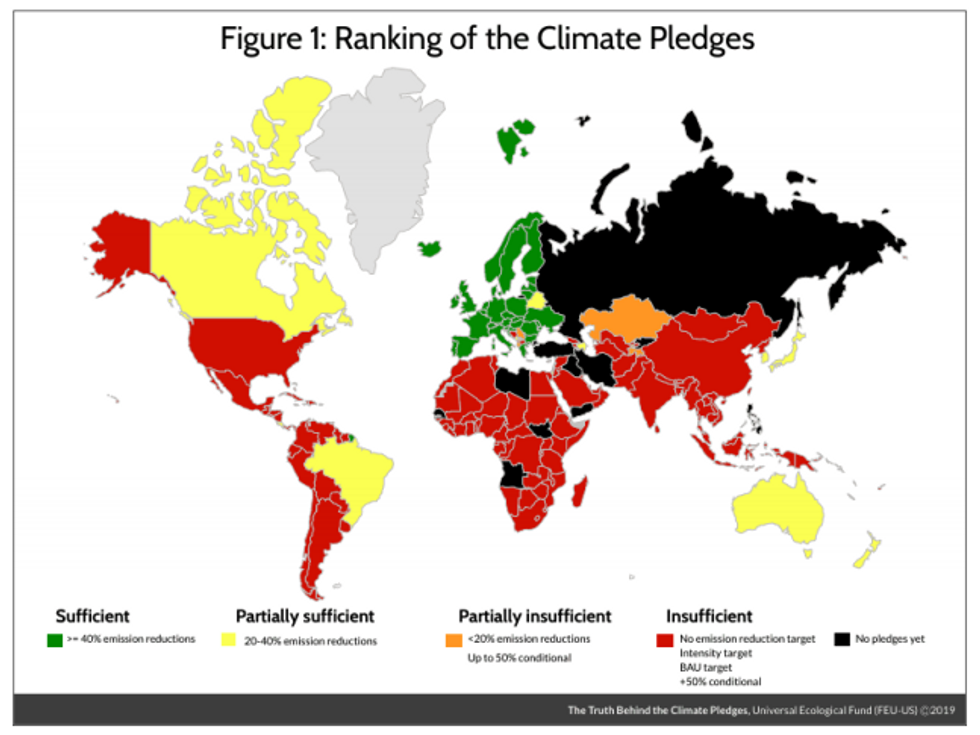

Three-quarters of Paris Agreement pledges judged insufficient

As the US begins to withdraw from the global climate pact, the remaining pledges fall short in stemming planet-warming emissions growth.

News for the United Nations just gets worse.

First President Trump, on the first day he could legally do so, officially began to withdraw the United States from the UN's Paris climate agreement.

A day later a new analysis finds three-quarters of the remaining pledges inadequate to meet global climate goals – with many unlikely to be achieved at all.

At least 130 of the 184 nations to sign the Paris Agreement in 2015, including the United States, are falling far short, according to the Universal Ecological Fund, a Washington, D.C.-based group dedicated to analyzing climate science. Those efforts under the agreement are supposed to reduce global emissions 50 percent by 2030 to limit average global temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

"With few exceptions, the pledges of rich, middle income and poor nations are insufficient to address climate change," says Sir Robert Watson, former chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and co-author of the report, "The Truth Behind Climate Pledges," released Tuesday.

"Simply, the pledges are far too little, too late."

The news came a day after Trump, in a move promised in 2017, formally began the year-long effort to extract the United States from pledges President Obama agreed to in 2015 as its part of the global agreement.

The U.S. agreed to cut its emissions by almost a quarter of 2005 levels by 2025, but Trump has spent the past three years rolling back environmental limits. State and local efforts are trying to fill the gap, the Ecological Fund said, but those efforts focus mostly on electricity generation and auto emissions and are failing to hit the mark.

China, the world's largest emitter, is expected to meet its pledge of "reducing its carbon intensity" by 60-65 percent from 2005 levels by 2030 – a measure that looks at the amount of CO2 emissions per unit of gross domestic product.

However, China's overall CO2 emissions increased by 80 percent between 2005 and 2018 and are expected to continue rising for the next decade, the report's authors concluded.

India, likewise, has vowed to cut its "emissions intensity" by 30 percent to 35 percent by 2030 – a promise it, too, is likely to keep. But like China, India's economy continues to expand, meaning its total emissions are likely to grow through 2030 due to economic growth.

The lack of ambition isn't limited to just the world's major emitters: Of the 184 country pledges in the Paris Agreement, 126 are partially or totally dependent on international finance, technology and capacity building. With no sign of international support for such efforts, many of those commitments may never materialize, the report concluded.

"it is naïve to expect current government efforts to substantially slow climate change," said James McCarthy, Professor of Oceanography at Harvard University and a co-author of the report.

There is one bright spot:

The European Union, with its 28 member states, stands alone among the five top greenhouse gas emitters to take an aggressive stand against climate change. The EU is expected to cut emissions 58 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, exceeding its Paris promise of "at least 40 percent of GHG emissions" below 1990's level."

The report ranks the EU pledge as sufficient.