Oil and gas production responsible for $77 billion in annual US health damages: Study

Proposed EPA methane limits may help curtail 7,500 yearly deaths from oil and gas production sites.

As the nation’s oil and gas output reaches record highs, new research shows that the harms from this boom go well beyond cranking up global temperatures.

According to the study, published in May in Environmental Health Research, air pollution from fossil fuel production alone kills 7,500 people a year in the U.S., while exacerbating 420,000 existing asthma cases and triggering 2,200 new incidences of childhood asthma. Health damages from the three air pollutants studied — ozone, nitrogen dioxide and fine particulate matter — carry an annual price tag of $77 billion.

Past research into the health risks of oil and gas has mainly looked at major combustion sources such as power plants and motor vehicles, Jonathan Buonocore, a public health researcher at Boston University and the study’s lead author, told Environmental Health News (EHN). “Nobody's looked at the health impacts of extraction,” he said. “So I decided to do that, and lo and behold, they weren't small.”

For years, the fossil fuel industry has touted natural gas — which is mainly composed of methane — as a safer “bridge fuel” between coal and renewable energy. “There's been a lot of people talking about the health benefits of the coal to gas transition in the power sector,” Buonocore said. This study suggests these health benefits have been overblown.

In the next few years, however, communities downwind of oil and gas production sites may begin to breathe easier. Proposed U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regulations, expected to be finalized next fall, aim to cut methane and other air pollutants from hundreds of thousands of oil and gas operations across the country. The agency expects that, by 2030, this rule will cut methane from these sources by 87% compared to 2005 levels.

Health impacts from oil and gas production

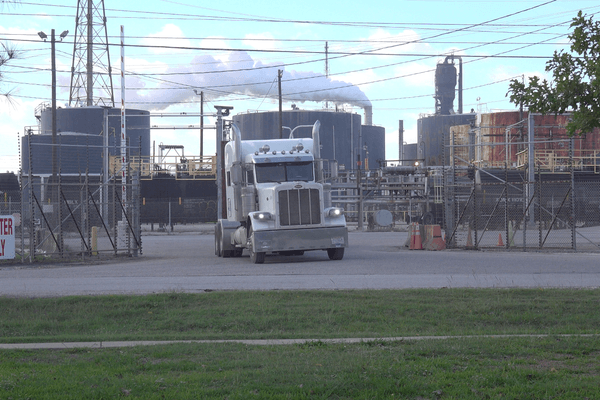

The Murphy oil drill site in South L.A. contains 22 active oil and gas wells and 7 injection wells. Credit: Nīa MacKnight

The Murphy oil drill site in South L.A. contains 22 active oil and gas wells and 7 injection wells. Credit: Nīa MacKnightOil and gas production sites are laced with invisible leaks. Methane and other air pollutants seep from wells — both active and inactive — and from equipment. The foul-smelling gas nitrogen dioxide, which forms when fossil fuels are burned, emanates from the flares used to burn off excess gas in oil deposits.

Methane isn’t particularly harmful on its own, but when it mingles with nitrogen oxide, heat and sunlight, it turns into ozone, the main component of smog. While ozone is beneficial high up in the atmosphere, where it shields the planet from damaging radiation, it acts as a powerful oxidizing chemical in our lungs, inflaming airways, triggering asthma attacks and aggravating chronic respiratory diseases. Long-term exposure is linked to low birth weights, diabetes and neurological disorders such as stroke and dementia. Infants and children, pregnant people and the elderly are particularly susceptible.

Fine particulate matter — formed from the combustion of oil, coal and gas, and from chemical interactions between nitrogen dioxide and other pollutants — is also a major air toxic. “Globally, this is the largest health risk in terms of air pollution,” Sarav Arunachalam, an atmospheric chemist at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and one of the study’s authors, told EHN. An estimated8.7 million people die prematurely every year from outdoor exposure to fine particulate matter, which carries many of the same health hazards as ozone. These minute particles, less than 1/30th the width of a human hair, are small enough to penetrate into the lungs and bloodstream, where they can kill via heart attacks, strokes or other cardiovascular events.

Drifting oil and gas pollution

For the study, the team ran EPA emissions data through computer models that simulate the chemical interactions of air pollutants, where they travel, and their effects on local communities. Predictably, ozone and other toxics are highest near their source, that doesn’t mean that places farther afield face no risks. “There were so many health impacts in areas downwind,” Buonocore said. This type of pollution are long-lived, and can ride atmospheric currents for hundreds of miles. “It’s regional,” It will stay in the air for two weeks.”

Cities including New York, Baltimore, Boston and Chicago caught the drift from oil and gas production, the study found. On a state scale, Illinois had the sixth highest risk, despite the fact that it produces very little oil and gas compared to the five most impacted states — Texas, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Oklahoma and Louisiana.

Karn Vohra, a public health researcher at University College London who was not involved in the study, told EHN that he was most concerned by the study’s finding that the health costs of oil and gas extraction outweighed the climate costs by a factor of five to seven. This research, Vohra said, “is an important piece of the puzzle to allow quantification of the health burden of the complete oil and gas lifecycle and inform policy.”

Despite the study’s alarming findings, the true damage to residents’ lungs and longevity may be even greater. The team looked at data from 2016, the most recent year available, which does not capture the recent boom in U.S. oil and gas development, Buonocore said. In addition, some data is likely undercounted. In Pennsylvania, for example, the EPA lists 72 compressor stations, although the state government permitted hundreds in 2013 and 2016.

“My guess is going to be that by and large, the emissions inventory going into this whole thing is pretty underestimated compared to the reality of what's on the ground,” Buonocore said.

Tackling methane at the source

The EPA’s proposed standards could cut an estimated 36 million tons of methane between 2023 and 2035 — the equivalent of cutting all greenhouse gasses emitted by the country’s coal-fired power plants in 2020. The new rules include regular leak inspections at well sites, emissions standards for compressors and other machinery, and the use of satellites to detect methane plumes. Per the EPA, “studies show that large leaks from a small number of sources are responsible for as much as half of the methane emissions from the oil and natural gas industry.”

Jon Goldstein, the senior director for regulatory and legislative affairs at the Environmental Defense Fund, told EHN that while he was largely satisfied with the proposal, “one piece of the puzzle that we're hoping will get addressed … is the issue of flaring.” Flares, he explained, hammer the climate on two fronts. Inefficient flares leak methane, which is 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide at heating the atmosphere, and is responsible for one-third of current planetary warming. Efficient flares convert most of their methane into CO2, which persists in the atmosphere for centuries, compared to methane’s 10- to 20-year lifespan. “The best way, we think, to address that problem is just to stop sending so much gas to flares in the first place,” Goldstein said. (Goldstein was not involved in the study, but an Environmental Defense Fund researcher was among the authors.)

Given how long greenhouse gasses persist in the atmosphere, it can take years, even lifetimes, for the benefits of climate policies to be felt. In contrast, said Arunachalam, “the air quality effects are immediate.” Shut down the sector, he said, and new and exacerbated cases of asthma due to these pollutants would swiftly come to a halt.

This study comes on the heels of other recent research into the health risks of oil and gas use. Another new report, co-authored by Arunachalam, found that roadway emissions of nitrogen dioxide and fine particulate matter are responsible for more than 400,000 premature deaths every year in the U.S., with minority communities bearing the brunt of the pollution. A 2022 study found that 13% of childhood asthma cases in the U.S. are directly tied to gas stoves.

The ubiquity of lung-damaging pollution along the oil and gas supply chain is another argument in favor of phasing out fossil fuels. But until the country transitions to renewable energy, “we don't want to see these health impacts continue at the rate that they are right now,” Goldstein said. “We need to tighten up the standards to protect people in the meantime.”