EPA rollbacks could endanger public health, experts warn

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's recent move to weaken air pollution and emissions standards could lead to more respiratory illnesses and premature deaths, health experts say.

Keerti Gopal reports for Inside Climate News.

In short:

- The EPA, under administrator Lee Zeldin, announced 31 regulatory rollbacks, calling it the most significant day of deregulation in U.S. history.

- Public health experts warn that loosening limits on particulate matter and toxic emissions could increase asthma, heart disease, and infant mortality.

- The agency's reconsideration of Mercury and Air Toxics Standards, which have significantly reduced mercury pollution, raises concerns about harmful neurodevelopmental effects on children.

Key quote:

“There’s no real safe level of these common air pollutants. Any increase in pollution has meaningful adverse effects on human mortality, and a reduction in these common pollutants has a benefit on human mortality.”

— Dr. Mark Vossler, board president of Washington Physicians for Social Responsibility

Why this matters:

Decades of research have established strong links between air pollution and serious health conditions, including respiratory diseases, heart problems, and developmental delays in children. Mercury exposure, a byproduct of industrial emissions, is especially dangerous for pregnant women and young children, potentially causing lasting cognitive and motor impairments.

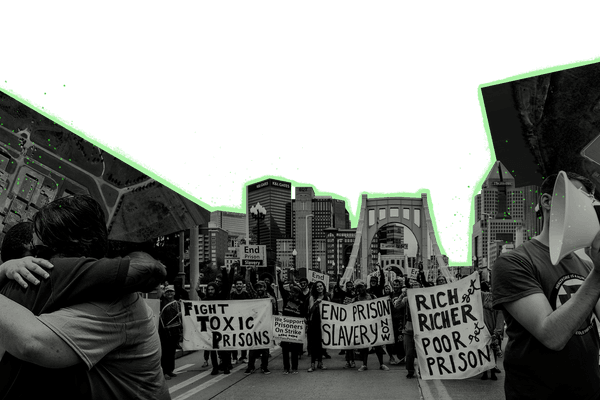

Weakening air quality regulations could have far-reaching consequences, particularly for communities already exposed to high levels of pollution—often those near power plants, factories, and highways. These communities, frequently lower-income and disproportionately made up of people of color, would bear the brunt of increased emissions. Beyond the immediate health effects, there is a broader concern that decades of environmental and public health progress could be undone, leaving millions at greater risk of preventable illnesses.

Related EHN coverage: In polluted cities, reducing air pollution could lower cancer rates as much as eliminating smoking would