Environmental reporting can help protect citizens in emerging democracies

Covering the environment is challenging and can be dangerous in any country. But fostering environmental journalism in emerging democracies is one way to hold government officials and powerful businesses accountable.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

What happens when an illegally logged tree falls or poachers kill endangered brown bears in the forest, but there's no journalist to report it?

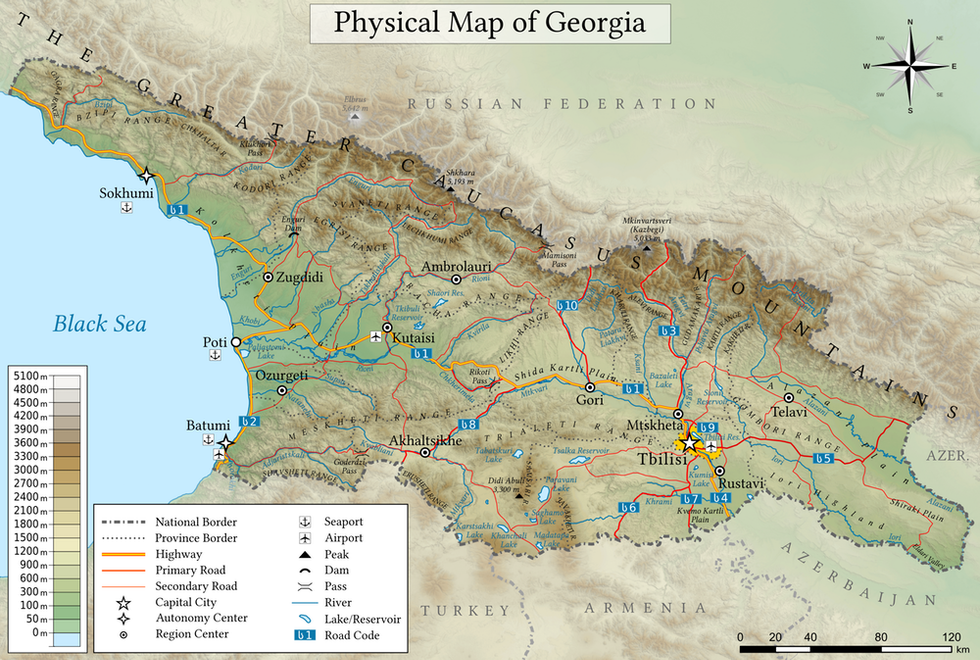

That's the situation in the Republic of Georgia, which faces challenges that include poaching, deteriorating air quality, habitat disruption from new hydropower dams, illegal logging and climate change.

The effects cross national borders and affect economic and political relationships in the Caucasus and beyond.

I researched environmental journalism in the Republic of Georgia as a Fulbright Scholar there in the fall of 2018. I chose Georgia because many of its environmental and media problems are similar to those confronting other post-Soviet countries nearly 30 years after independence.

As I have found in my research on mass media in other post-Soviet nations, journalists risk provoking powerful public and corporate interests when they investigate sensitive environmental issues.

But when the media don't cover these problems, Georgians go uninformed about issues relevant to their daily lives. Eco-violators operate with impunity, and the government and Georgia's influential private sector remain opaque to the public.

At a time when government hostility to journalists is rising in many countries, Georgia illustrates how environmental damage, pollution and ill health can spread, and go unpunished, when powerful interests are unaccountable to the public.

An unstable mediascape

Georgia's habitats range from alpine peaks to river floodplains and the Black Sea coast. (Credit: Giorgi Balakhadze/Wikimedia, CC BY)

Levels of press freedom, autonomy and media sustainability have fluctuated since Georgia became independent in 1991. The latest constitutional change greatly strengthened Parliament and eliminated direct election of the president, whose office is primarily ceremonial.

The governing Georgian Dream coalition has become increasingly anti-press over the past two years. Georgia's mediascape is fairly diverse but dominated by its two largest television channels.

The 2019 World Press Freedom Index ranks Georgia 60th out of 180 countries, a substantial improvement from 100th in 2013. However, it notes that media owners still often control editorial content, and threats against journalists are not uncommon.

Shallow, uninformed coverage

In addition to my own observations during 3 ½ months based in Tbilisi with visits to other cities, my findings draw on input from 16 journalists, media trainers, scientists and representatives of advocacy groups and multinational agencies whom I interviewed or who spoke to my media and society class at Caucasus University.

Source after source bemoaned what they saw as generally shallow, sparse, misleading and inaccurate coverage of environmental topics. In their view, the legacy of Soviet journalism as a willing propaganda tool of the state lingered. Tamara Chergoleishvili, director general of the magazine and news website Tabula, put it bluntly: "There is no environmental journalism… There is no professionalism."

One major complaint was that journalists lacked knowledge about science and the environment. "If you don't understand the issue, you can't convey it to the public," said Irakli Shavgulidze, chair of the governing board of the nonprofit Center for Biodiversity Conservation & Research.

Another concern was that journalists often failed to connect environmental topics with other issues such as the economy, foreign relations, energy and health. Sophie Tchitchinadze, a United Nations Development Programme communications analyst and former journalist, said the Georgian media was just starting to view itself as "an essential part of economic development and equally important to social issues."

Transparent in principle, not in practice

Lack of access to information was also a common complaint, despite transparency laws entitling the public and press to government documents.

For example, when Tsira Gvasalia, Georgia's leading environmental investigative journalist, reported on the nation's only gold mining company, she was unable to obtain full information on possible government actions from the local prosecutor, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture or the courts. "The company has a close connection with the government," she noted.

Georgian citizens weren't much help either. In the small mining town of Kazreti, Gvasalia saw thick layers of dust on roads and bus stops from uncovered trucks transporting ore to the company's processing facility. When she asked residents how pollution affected their everyday lives, people were "very careful. Once I mentioned the name of the company, everybody went silent. … Everyone worked for the company," she said.

Who sets the priorities?

In my sources' view, environmental coverage was not a priority for Georgian journalists and media owners, especially at the national level. Lia Chakhunashvili, a former environmental journalist now associated with the nonprofit International Research & Exchanges Board, observed that covering the environment "is not as glamorous as being a political reporter or on TV all the time or having parliamentary credentials."

"If the environmental sector becomes a priority for the government, journalists will try to cover it better," Melano Tkabladze, an environmental economist with the Caucasus Environmental NGO Network, predicted.

What coverage exists is weakened by misinformation, disinformation and "fake news." Much of it originates from Russia, which briefly invaded Georgia in 2008 to support two breakaway provinces seeking independence, and vehemently opposes Georgia's efforts to join NATO and the European Union.

Tabula's Chergoleishvili asserted that Georgian journalists could not distinguish fake news from legitimate sources. As an example, Gvasalia described planted reports on Facebook that claimed a hydroelectric project would "elevate local people" and provide "great social benefit." "Seventy percent of this needs to be double-checked," she warned.

Cultivating better reporting

Although Georgia's media sector remains politically and economically vulnerable, I see two encouraging signs. First, young journalists are increasingly interested in covering the environment.

Second, Georgian leaders strongly desire to join the European Union, where multinational eco-issues such as curbing climate change and building a pan-European energy market are priorities.

This step would be significant for Georgia, given the trans-border nature of environmental problems, the country's progress toward energy self-sufficiency and its strategic location.

Climate Change Adaptation Programme worth $70 mln has been launched by the #Georgian Government as an important step to protect the country from natural hazards and to reduce negative effects of #ClimateChange to minimum.

— MFA of Georgia (@MFAgovge) February 19, 2019

In the meantime, more support for independent fact-checking could improve Georgian environmental coverage. Some already occurs: For example, FactCheck.ge, a nonpartisan news website based in Tbilisi, critiqued a claim in 2016 by Tbilisi's then-mayor, who had campaigned on a promise of bolstering the city's green spaces, that the city had planted a half-million trees.

The larger truth, it reported, was that many planted saplings were extremely small and closely packed. A large fraction had already dried up and were unlikely to survive.

Another partial solution would be for environmental nonprofits to offer the Georgian media more press tours, trainings and access to experts. However, eco-NGOs also have agendas and constituencies, so this type of outreach can't substitute for informed professional journalism.

Covering the environment is challenging and can be dangerous in any country. But fostering environmental journalism in emerging democracies like Georgia is one way to hold government officials and powerful businesses accountable.

Eric Freedman is a professor of journalism and Chair, Knight Center for Environmental Journalism, at Michigan State University.