Scientists probe ancient history of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet and find unsettling news about sea level rise

The eastern Antarctic Wilkes Basin ice sheet seems to have receded during a warming event about 400,000 years ago—such a loss could add an additional 13 feet to sea level rise in the future

Researchers have found evidence of ice loss from Wilkes Basin in eastern Antarctica during a climate warming event 400,000 years ago, which suggests that parts of the East Antarctic ice sheet could be lost to modern warming trends—ultimately resulting in an additional 13 feet of sea level rise.

Scientists believe that over the last few million years, Earth's climate has oscillated between cooler periods when ice sheets spread across the poles and warmer periods when those ice sheets partially melted and sea levels rose. Climate scientists study these warmer periods hoping to refine climate models and make better predictions about the future impacts of human-caused climate change.

While the ice sheets of Greenland and western Antarctica have long been identified as vulnerable to climate change and drivers of sea level rise, the status of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, the largest freshwater reservoir in the world, has been more ambiguous, with some suggestion that it has been stable for millions of years and resisted past warming events.

However, in a Nature paper published today, a team of researchers present evidence that the ice sheet covering Wilkes Basin in East Antarctica receded roughly 435 miles during the Marine Isotopic Stage 11, a particularly long period of warming that occurred roughly 400,000 ago. During this time, the Earth's average temperature increased between one and two degrees Celsius, an increase comparable to modern climate change projections.

Sea level rise happens relatively slowly—the global average sea level has risen about nine inches over the past 140 years, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

But the finding that the Wilkes Basin is less stable than originally thought substantially adds to the problem—experts estimate that over the coming centuries the combined ice sheets of Greenland, western Antarctica, and, now, the Wilkes Basin, could cause sea levels to rise by 42 feet.

"For a long time now, it's been very difficult to reconstruct…what's happened to ice sheets in response to warming events," Terrence Blackburn, assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences at University of California, Santa Cruz and lead author on the new paper, told EHN. "As soon as those glaciers re-advance during that cold period, they would cover up and destroy all that evidence. But what we have found is that there is another…archive of how long the ice has been stable."

Blackburn's team used an analysis of uranium isotopes in mineral samples dated from different times in Wilkes Basin history to create a timeline of glacier advance and retreat. Water, which typically contains trace amounts of uranium, naturally becomes enriched with a specific isotope of uranium, uranium-234, because of interactions between the water and rocks.

If this water is in a free-flowing source, like a stream, the uranium isotope gets diluted and never builds up. However, the researchers found that water trapped under glaciers will build up high levels of the uranium isotope.

This water will refreeze at the edges of the glacier and its minerals will all precipitate out, forming opal and calcite deposits. The uranium-234 content of the glacier water is effectively recorded inside these deposits. By locating and dating the deposits, researchers can learn what the isotopic makeup of the subglacial water was at the time the deposit was formed.

The researchers found that during the Marine Isotopic Stage 11, uranium-234 enrichment levels dropped, and then began to slowly build back up.

The researchers believe the decline in uranium-234 enrichment occurred as glacial waters in the Wilkes Basin were flushed out by melting ice and sea water. But then, as temperatures cooled, the glacier began to reestablish itself and sequester enriched water in the Basin once again.

"People haven't really used this technique to infer retreat of the margins of the ice sheets before, so it's really cutting edge in that sense," Andrea Dutton, a paleoceanographer at University of Wisconsin-Madison and expert in sea level change who was not involved with the study, told EHN.

She added that, like areas of concern in western Antarctica, the Wilkes Basin ice sheet sits on ground that is below sea level. This structure makes glaciers more prone to melting as ocean water warms.

"Understanding how susceptible these vulnerable parts of the ice sheet, these marine base portions are is the biggest question right now in terms of providing accurate sea level projections for the future," said Dutton.

Robert Kopp, director of the Rutgers Institute of Earth, Ocean & Atmospheric Sciences who was not involved with the study, said that other areas of Antarctica, such as the Antarctic Peninsula and Thwaites Glacier, face a more near-term threat than Wilkes Basin, but that future melting in eastern Antarctica could be catalyzed by decisions that humanity makes today.

"What this is really about is…sea level commitment," he told EHN. "That is, if we warm the planet up two degrees, how much sea level rise do we expect to see over the coming many centuries to millennia as a result of that? What is the world we are creating for our descendants?"

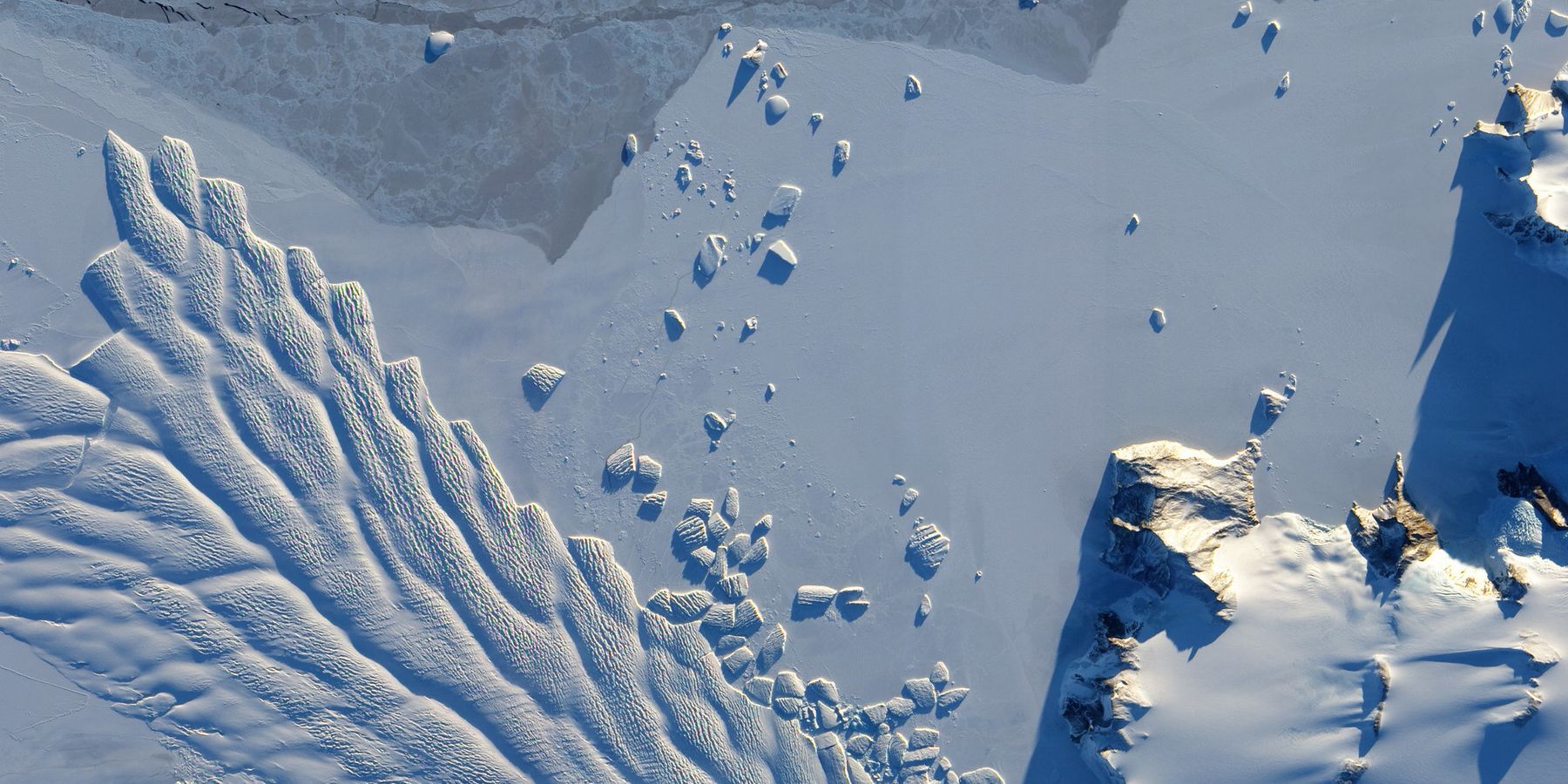

Banner photo: The Matusevich Glacier flows toward the coast of East Antarctica. (Credit: NASA)