What climate change means for globe-traveling Saharan dust

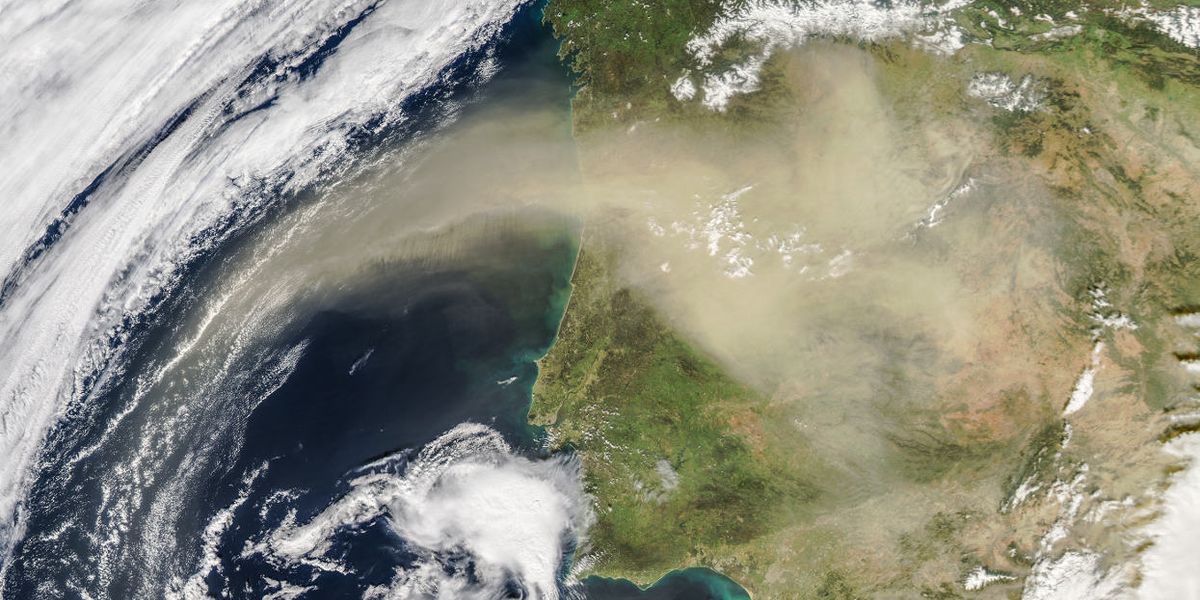

As Sahara Desert dust makes its annual trip across the Atlantic into US air, scientists are seeking answers on what global warming means for future dust amounts, which could have a major influence on extreme weather and human health.

Reddish-brown spots show up on cars after a brief rain shower. A ring of mud appears in a white bucket put outside to collect rainfall. Sunsets might look more vivid, but the sky is hazier.

These are all signs that Saharan dust is blowing across the Atlantic Ocean to parts of North America, which it does every year from around May through July. This year's dust is just reaching the U.S. now, and when it does, it's "quite obvious" in Miami, according to Joseph Prospero.

"The sky, which here in Miami tends to be a nice, clear, crisp, blue, instead it has sort of a grayish, opalescent quality," he told EHN. "You'll get dust along the windshield wiper, where you can just wipe it off… Because it's traveled so far, there are only fine particles. It's like rouge, like face powder."

Prospero might notice the dust more than most people do. A professor emeritus at the University of Miami, he has studied Saharan dust for decades. The Sahara Desert in Northern Africa is the largest arid region in the world — approximately the size of the continental United States. It blows hundreds of tons of dust into the air every year, affecting places across the globe, like Africa, Europe, the Caribbean, and the U.S., including states away from the coast, like Missouri and Kansas.

The dust has many effects, both good and bad. For example, it is carried by dry air and suppresses cloud formation, so its presence means fewer dangerous tropical cyclones. But the dust is also associated with health conditions like dry skin, asthma, and desert lung syndrome, a chronic condition where small particles build up in the lungs and damage blood vessels and air sacs, making it difficult to breathe.

Because of the impact Saharan dust can have on weather and health in places near and far from the desert, scientists are trying to tease out whether climate change will impact this annual phenomenon. They're running powerful computer models with the hopes they can get a better idea of what to expect—because tilting the scales either way on dust amounts could affect the surrounding areas in myriad ways.

Some models suggest that dust will decrease in the future. However, the relationship between a warmer planet and globe-traveling dust remains a crucial mystery yet to be solved.

"A small change in how much dust is blowing off of Africa could have huge global implications," Amato Evan, an atmospheric scientist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego, told EHN.

Data and dust

Studying the dust directly is tough in North Africa—what Evan calls a "data-sparse" region. "There aren't very many weather-observing stations where people have been measuring dust emission. These very active regions where dust is being produced all the time have almost zero observation," Evan said.

There is also a data gap in air quality monitoring in low- and middle-income countries. Remote, rural areas and developing regions are less likely to have equipment set up to monitor air pollution, meaning that it's hard to tell just how much dust is in the air in areas close to the Sahara, which are affected most by the dust.

Predicting future dust amounts from the Sahara largely depends on whether the region's climate becomes wetter or drier. Climate models have been mixed on this. Future changes in rainfall are harder to predict than changes in temperature because they depend on so many factors. Warmer air can hold more water, but it will not change rainfall uniformly across the globe. It is also harder to predict changes in precipitation over land than over water due to changes in temperature and humidity.

A drier desert would mean dust would increase, while a wetter desert would reduce dust. In addition, increased amounts of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere could heat the Sahara and weaken winds, causing less dust to enter the air.

There is currently no apparent trend in how much dust is blown away from the Sahara each year. Some decades, like the 1970s and 80s, have had more dust, while others had less. One study led by Evan tried to predict future dust amounts using computer modeling. A large fraction of the simulations, about 44 percent, showed a significant decrease in Saharan dust in the future.

"This is a very interesting result and something worth keeping an eye on," Evan said. However, he added that the models showed many other results; some showed a smaller decrease, while others showed negligible change or an increase in dust.

Evan believes that modeling future climates is a first step at trying to understand what would happen if dust amounts do change.

"If we want to understand what's going to happen with dust in the future, we have to understand what's happening in the Sahara because it's such a major global player," he said.

The Sahara has grown by about 10 percent over the last 100 years. But thousands of years ago, it was green and full of plant life. Fluctuations between humid and dry Saharan climates are partially caused by the tilt of Earth's axis, but human activities may have played a role in the timing of the switch, and could affect the Sahara in the future.

Good news, bad news

Credit: Sergey Pesterev/flickr

Other studies have found that if the dust were to decrease in the future, it could cause an increase in tropical cyclone activity. A simulation with less Saharan dust in the atmosphere showed an increase of about two more tropical cyclones per year. The cyclones in the model weren't significantly stronger than normal, but they did last almost a day longer on average.

"One of the more interesting things that came out of this is that the [simulated] storms seemed to be significantly longer lived. That's potentially because we saw a lot more of these storms forming in the main development region off the coast of Africa," Kevin Reed, an atmospheric scientist at Stony Brook University and lead author of the study, told EHN.

The interplay between dust and climate makes the situation even more complicated. A wetter or drier environment can influence the amount of dust, but in turn, dust can affect climate by decreasing rainfall through suppressing clouds and lowering temperatures by partially blocking out the sun.

"Not only can dust affect climate, but climate affects dust. So there's a possible feedback loop," said Prospero.

A decrease in Saharan dust might not be entirely bad. Although it could increase hurricanes, it's also possible that lower dust amounts could help people breathe easier. One study done by researchers in Spain found that larger Saharan dust particles (meaning more than 1/20 of the width of a human hair) were correlated with increased mortality for people in Barcelona.

Just how much the dust affects health has been difficult to determine, as few studies have been done in places like North Africa and the Caribbean that are most impacted by the dust.

The composition of Saharan dust may make it relatively more benign than other types. While household dust is made of mites, skin cells, hair, and textile fibers, Saharan dust is more uniform, mainly composed of minerals like quartz and feldspar – although the composition of dust can vary depending on what region of the Sahara it comes from. "It tends to be pretty clean compared to the dust particles under the bed," said Prospero. Still, he said, "there certainly could be health effects."

The dust, coming from a remote desert and difficult to predict, is also affected by multiple climates in the Sahara and surrounding areas. Prospero noted the difference between the arid Sahara and the tropical, wet environment near the Gulf of Guinea, about 600 miles away.

"It's as if I left Miami and drove to visit my son in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, I would be going from a tropical environment to a deep desert," he said. "So it's a very difficult region to predict… it's a tough call."