Competing visions for a famed river in a Midwest hotspot—Part 2

This 2-part series explores two projects on Michigan's Grand River and how a fast-growing region is struggling to define a relationship with the river it was built around.

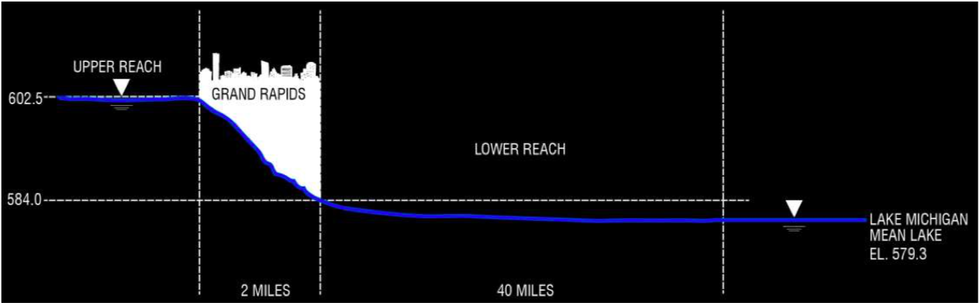

GRAND RAPIDS, Michigan—After dropping through downtown, the Grand River flattens out. There, the state is considering a dredging project to open the river to larger boats and travel between Grand Rapids and Grand Haven, a city at the river's mouth where it empties into Lake Michigan.

And, like the rapids restoration and riverbank improvements planned for downtown, this project is raising questions about what a city does with the river it grew up around. Can a thriving city and its surrounding area pursue both environmental and economic health? A vocal portion of the public argues that—due to history, ecology or economics—the dredging project cannot.

That project, the Grand River Waterway, would make 22.5 unmaintained miles of the Grand River navigable to boaters, opening access to Grand Rapids from Lake Michigan. Proponents say buoys and dredging parts of the river would make it safer for nonlocal or inexperienced boaters and increased traffic would generate revenue that far outstrips the project's cost.

But if dam removal feels like undoing past mistakes, dredging, for some, feels like repeating them. Unlike the rapids restoration, the Grand River Waterway has met strong public opposition.

See Part 1: Responsibly restoring rapids

Opponents say the project will reduce water quality, erode riverbanks, disturb pollutants trapped in the river bed and ruin wildlife habitat in the name of making money. They say that due to ongoing maintenance and other expenses the project won't make as much money as promised.

"It's just going to be a super elaborate, expensive practice to try to get some very large boats up and down the lower river," Bryan Burroughs, the executive director of Michigan Trout Unlimited, told EHN.

The project is the next front in the region's struggle over its use of the Grand River, its defining natural resource.

Habitat concerns

Credit: Grand Rapids Whitewater

Dan Hibma, the proposal's originator and a board member of Grand River Waterway, rejects notions that the waterway project is a case of abusing the river for economic gain. Because of the project the state conducted the first ever topographical study and mussel study of the river. The next step is to test the sediment at the dredge sites to see if dredging would stir up toxic chemicals left over from the river's industrial use. The state has the funding and permits.

"Let's do the soil test and see what's in it," Hibma said. "That'll be a factor if the project moves ahead or not."

Many who are supportive or optimistic about removing the dams to restore the rapids don't like the idea of dredging the river.

"As we're trying to restore the river and improve the habitat, knowing what we know about endangered mussels and how much the river has been modified, this would be kind of a setback," Wendy Ogilvie, director of environmental programs for Lower Grand River Organization of Watershed, told EHN. "It's never a recommended practice to dredge a river."

Ogilvie is working on riverside improvements in conjunction with the Grand Rapids Whitewater project, an initiative to restore the historic rapids on the Grand River in downtown Grand Rapids and rework the riverbanks to provide places for residents to connect with each other and the river.

"I'm hesitant because in general, dredging projects ruin habitat," Al Steinman, the Allen and Helen Hunting director of the Grand Valley State University Annis Water Resources Institute, told EHN. "I don't think there's any way you can avoid destroying some important habitat in the Grand River."

He also has concerns about the cost of the project. Grand River Waterway estimates the cost of dredging to be $2 million dollars, which will draw in $5.7 million annually and increase property values along the river by $54 million. Critics say this underestimates the cost of ongoing maintenance and overestimates the economic gains.

"There's a lot more that needs to be explored here, in terms of what those costs are," Steinman said. "Until those are fully understood and acknowledged, this project definitely needs to be put on hold."

"Is that the best and highest use of the river?"

Paw prints along the Grand River. (Credit: Andrew Blok)

Some costs aren't financial.

"We've lost approximately 90 percent of our coastal wetlands in the Great Lakes since Europeans have visited here," Steinman said.

If the Grand River is dredged for greater use, that could mean increased development along the shoreline. It would be hard to imagine this wouldn't be detrimental to the remaining wetlands, Steinman said. Wetlands store carbon, protect coastlines, provide critical habitat for fish and wildlife and are aesthetically valuable.

"Is that the best and highest use of the river? That's a societal decision, but I can tell you as society gets informed by science, certainly we're going to see there's going to be negative impacts associated with this. Can that be outweighed by the economic benefits of marinas? I think that depends on your perspective," Steinman said.

The proposal has sparked backlash among landowners, municipalities, environmentalists and those who already use the Grand River recreationally.

"There are so many reasons it doesn't make sense," Jeff Seaver, a founding member of the grassroots opposition group, Friends of the Lower Grand River, told EHN.

Michigan's Department of Natural Resources says extensive dredging of rivers results in worse water and streambed quality that harms wildlife.

It would be an unnecessary disruption to an ecosystem starting to recover from the abuses of industry and development, Seaver, who is also an avocational local historian, said.

He said past dredging has quickly filled in again, signaling high ongoing maintenance costs.

"We know from history it's been a futile attempt," he said. "Any attempt to dredge the river is taking a bunch of steps backward."

"Why wouldn't we want to have more recreation?"

Anglers on the Grand River in downtown Grand Rapids. (Credit Andrew Blok)

The proposal has also been attacked as a personal money-making venture by Hibma at the expense of the river's health. Hibma owns 200 acres along one mile of the proposed waterway site.

Hibma says the plan is an attempt to open the river to more recreation, not make money for himself from the river's increased traffic.

"We're a recreation state, that's a big part of our economy," he told EHN. "I don't have any hotels. I don't have any gas stations. This is a great asset that we have in West Michigan, and why wouldn't we want to have more recreation?"

Some opponents are calling on state officials to stop the project with or without further study.

"This is ultimately in the state legislature's hands. They created this problem and they need to fix it and defund it," Jeff Seaver said.

For now, the project is caught up in politics and dueling reports. A Michigan State University researcher wrote a study that said the project could lead to poorer water quality, increased erosion and harm to fish and wildlife. An evaluation of that study posted to Grand River Waterway's website says the report is flawed. Hibma said the study's author set out to stop the project.

The project's schedule is hard to predict as the Department of Natural Resources determines if and when to test the streambed for contaminants. The department did not return a call seeking that information.

Putting the Rapids back in Grand Rapids

Sixth Street Dam in Grand Rapids. (Credit: Andrew Blok)

Both projects, the Grand River Waterway and the rapids restoration proposed for the Grand River are modifications to serve human interests—both for recreational purposes. But from there it seems the similarities stop, certainly regarding public response.

Acceptance and rejection have something to do with understanding West Michigan's past relationship with the river and deciding how it will look moving forward.

"Putting the Rapids back in Grand Rapids" and restoring a missing piece of the town's identity, has inspired some civic pride, said Andy Guy.

Bryan Burroughs noted the appeal of removing the dams.

Janet Korn, who sits on the board of Grand Rapids Whitewater, is excited to hear the roar of the rapids that have been silenced for years.

History and "the idea that we would make the same sort of mistakes that were made years ago and set things back" is a key driver of his opposition to dredging, Jeff Seaver said.

A bike ride out of town, along the river, includes a significant change in soundscape. Starting in downtown at the Sixth Street Dam, the river makes noise, but doesn't roar. Construction noise and traffic from two busy highways are most obvious.

But riding the decline that once made for deafening rapids eventually brings you to Millennium Park, outside the city on the river's flat, slower run to Lake Michigan. If it weren't for Interstate 196 in the distance, the bird and insect calls, the wind through the trees and the gentle sound of the river is closer to what one might have heard 150 years ago.

In another 20 years, the river downtown could roar like it used to, while downriver might be noisier with boat traffic.

It depends on what Grand Rapids and West Michigan decide for the river they grew around.