She could see the Hudson branch—one of the three streams that converge at the Patapsco River—which runs under the building, start to rise, but she wasn't concerned. It always rose a bit when it rained.

But then the water started to flood the restaurant's basement. She could see seven of the basement steps above water. Two minutes later, she said, there were only five.

Then the water came down Main Street, as Radinsky and her staff tried to leave the restaurant. It was already knee deep. It would eventually reach the second story of many of the buildings.

"That's when one of my servers turned to me and said, 'This is happening again,'" Radinsky said.

A week after the flood, Radinsky said she is exhausted and stressed. She's also experiencing depression and a sense of uncertainty. Radinsky also lived on Main Street—the flood waters swept away both her job and home of two months.

"In an afternoon you have everything taken away," she said. "And you have no idea where to start… It's just very mentally overwhelming all at once and it just tires you out."

Radinsky is not alone: Psychologists trained in disaster psychology say after a traumatic event like a flood, people can experience stress, depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, although they are quick to point out that each case is individualized.

Going through a flood for the second time can worsen these responses, they said. And adding to the stress and trauma is the question of whether or not to rebuild.

No stranger to floods

Credit: Heather Mongilio/EHN

Ellicott City was founded in 1772 around Main Street, "for a very specific reason. It's a mill town," said Andy Miller, professor at University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Three tributaries and the Patapsco River powered the mill. Nowadays, Main Street is lined with mom and pop stores and parked cars. In the summer months, visitors and residents walk the streets, popping into the local businesses or attending one of the summer movie nights at The Wine Bin.

Main Street is no stranger to floods. At the bottom of the street, against the train bridge, is a wooden pole with several marks indicating the water levels the street has seen.

The highest belongs to the flood in 1868 when the Patapsco River rose and more than 20 feet of water was on Main Street. The next marker is from 1972 when Hurricane Agnes caused the river to rise to about 14.5 feet.

The street's residents and business owners were still recovering from a flash flood in 2016 that ripped up the road and gutted businesses when another storm hit May 27, dumping almost nine inches of water on the area.

The streets filled with water, almost as high as the second floor of many of the buildings on Main Street. When the rain stopped, the rebuilt businesses were once again destroyed and many, like Radinsky, were left without a home.

A flood’s psychological impact

Credit: Sarah Radinsky

When events, like the flood, become overwhelming, they become traumatic events. That can lead to traumatic stress, said Gerard Jacobs, professor emeritus at the University of South Dakota. It's important to note that traumatic stress is not abnormal or a sign of mental illness.

"Traumatic stress reactions are not a sign of weakness. It's just a sign of being human," he said.

People often feel fear, anxiety, sadness, depression, anger or guilt, he said. Typically the stress lasts about four to six weeks, he said.

But it can last longer, said Dr. Emanuela Taioli, director of the Institute of Translational Epidemiology at Mount Sinai. Taioli has been studying psychological reactions from Hurricane Sandy and found that the anxiety lasted more than a year.

Jessica Lamond, a professor at University of West England Bristol, who studies flooding in the United Kingdom, said that she has found people have anxiety about rain as much as five years after severe flooding.

In addition to stress, people might also experience post-traumatic stress disorder, especially in cases where a friend was in danger or the water started reaching them, Taioli said.

Dave Carney, the owner of The Wine Bin, located on the top of Main Street, said during the flood he felt anxious, as well as helpless. He was at his home in Catonsville, less than four miles away, and he could not get to his store, where his business partner and employees were working. He was getting updates from his partner, and she told him they were going to the second floor of the building then evacuating to another.

"That's when you're like 'it's worse than ever.' It's just terrifying," he said.

For Carney and Radinsky, the psychological impacts may be worse. Taioli found that people who had gone through flooding before Hurricane Sandy fared worse than the people who were experiencing their first flood.

A second flood can be demoralizing, said Richard Tedeschi, professor of psychology at University of North Carolina Charlotte. But having gone through a flood might mean that people know how to handle it and what the recovery process is.

With such psychological impacts—and the threat of more flooding, will the residents and business owners try to rebuild?

To rebuild or not to rebuild

Credit: Sarah Radinsky

After the 2016 flood, the message out of the community was that they would rebuild and be back. But after the second flood in two years, people aren't as quick to say they'll be back.

Radinsky said she has already talked to her landlord about coming back. "I still have the patience and the drive," she said.

Carney said he is planning on coming back. His store did not have too much damage and they lost minimal inventory. But it also depends on the other business owners. He can't run a business on an empty street. And what if he comes back and it floods again?

"Last week I had a business that had value. Now I have a business with no value… that's emotionally hard," he said.

While there are some staple business coming back, others have decided to relocate.

The decision of staying or leaving is a difficult one. If people viewed the 2016 flood as an anomaly, it's easier to say they'll be back, Tedeschi said. When it happens again, people have to make some more decisions about safety. But some will stay because of emotional attachments to their homes and businesses.

"They stay there because it's home. The sense of rootedness is important to people," he said.

Deciding to leave the area is not necessarily a sign of avoidance, Jacobs said. It might just be the rational choice for some.

A sense of community can play into the decision to stay or leave. And community members can also help people with their mental health. Paul Hudson, a doctor of psychology at the University of Potsdam in Germany, found that floods can bring communities together and help people rebuild.

Psychologists recommend the community members not affected by the flood be a listening ear for people who need to talk. It can help them work through the traumatic event, they said.

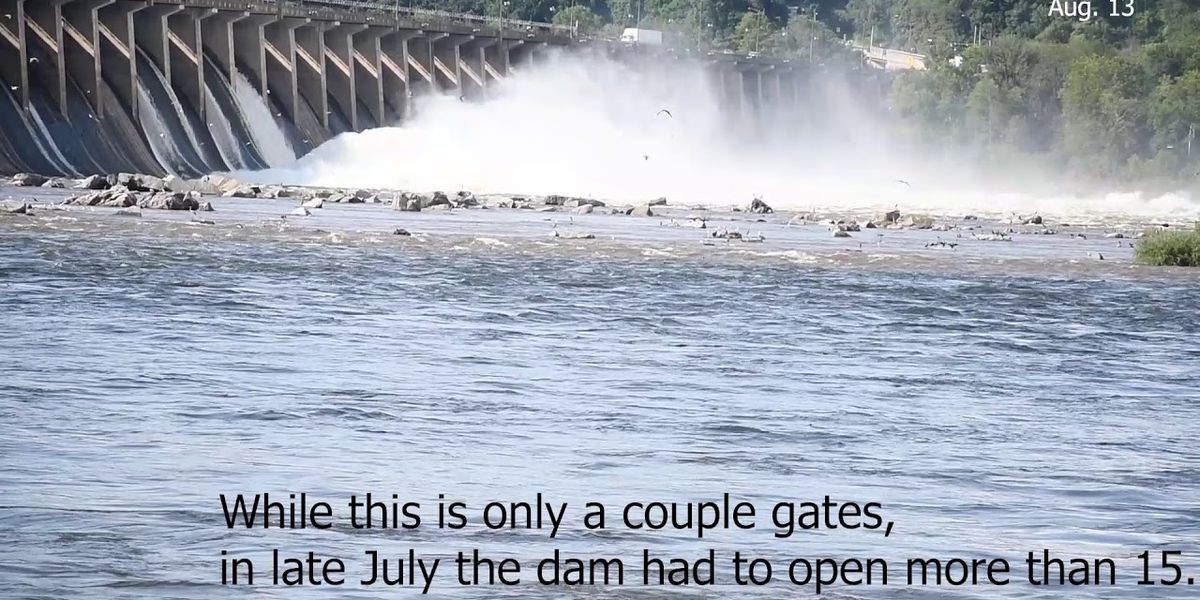

Will it happen again?

Credit: Heather Mongilio

The area is naturally flood prone. Despite the common saying that the 2016 or 2018 floods were thousand year floods, they were really floods that had a one in 1,000 chance of happening, meaning they could happen each year, Miller said.

And with two floods happening so close, it raises the question: is it because of climate change or the development of land around the area. The answer? Probably a little of both.

Professor Ben Zaitchik at Johns Hopkins University said climate change makes the air warmer, and warmer air holds more water. That said, he's not sure if the Ellicott City flooding is entirely a climate change story.

"It's going to rain hard sometimes. And if you took away the land cover that soaked that into the ground, and you built in a valley with the hard bedrock underneath it that's impermeable, you're going to flood," he said.

The U.S. Geological Survey measures the peak flow from floods by using high water marks in the Hudson, Tiber and New Cut branches, which lead to the Patapsco River. While they haven't done the analysis yet, Jonathan Dillow, a supervisory hydrologist with the USGS, said that they found high water marks that were at least as high as the ones from the 2016 flood. In the case of the New Cut branch, they might have been about a foot higher. "So it was a lot of water, and it was very high," he said.

And with that amount of water, there would likely be flooding, even if there was more pervious surface, Miller said. The two storms might not be as rare as people think, he said, adding that climate change could increase the risk of flood-producing rains. He also said that storms like the one in May happen often in a 30-mile radius. It's just rarer for them to strike the same area so soon.

"Is it possible that the same event will occur again in another two years? It's possible. Is it possible we won't see an event like that for 100 years? I think that's also possible," he said.

The clean up in Ellicott City has just started, and it is unclear how long it'll take for the area to reopen, for people to be able to open their businesses and for others to return to their homes. For Radinsky, it almost felt like she has to return, she said. And she hopes it might encourage her neighbors to come back too.

"It's still Ellicott City. It's just a different version of it," she said.