Commentary: Choose a climate savvy UN Secretary General for global stability.

The next Secretary General needs a skill set that matches 21st century challenges.

The UN General Assembly will select a new Secretary General in the remaining months of 2016. Who might be chosen depends on how the 193 member states (on recommendation from the Security Council, each of whose five members essentially have a veto) weigh a lot of complicated factors.

These include attention to the UN’s informal rotating regional balance (which argues this time for a candidate from Eastern Europe), gender (for the first time half of the candidates are women) and administrative and diplomatic skills.

A critical criterion for selection should be a careful assessment of candidates’ skill sets compared to the risks facing the world in the upcoming five years.

The SG acts on behalf of the member states but also on behalf of the people of the world. By the terms of the UN Charter, the SG can "bring to the attention of the Security Council any matter which in his (sic) opinion may threaten the maintenance of international peace and security."

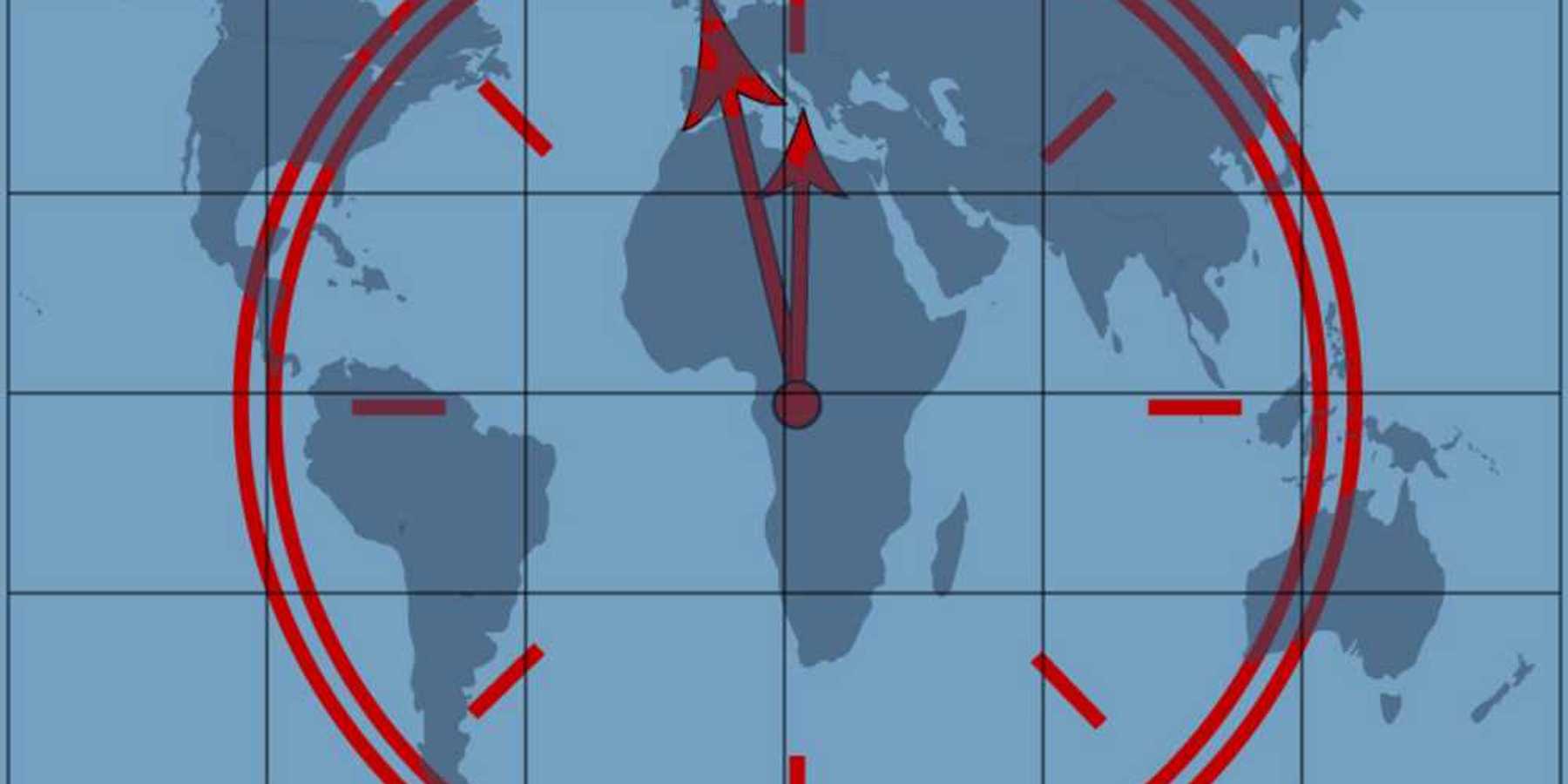

In other words, the SG must always be scanning the horizon to identify those not so obvious threats that, left unresolved, might explode into conflict or create costly global disruptions.

To our knowledge, a deep understanding of climate change and commitment to addressing this challenge has not before been on the list of qualifications for an SG.

But today, a now-swiftly changing climate is precisely one of those conditions complicating each of the already complex challenges that make up the UN portfolio. Led to these insights by defense professionals, it has become increasingly apparent that climate change is an important and growing factor in global stability.

Perhaps the best example of this is water. Long-standing tensions over that essential resource are being intensified by changes in average weather conditions. In other words, historically rare extended droughts and (paradoxically) excessive flooding and high water events are increasingly more common.

Instability with impacts on agriculture and food security is stoking already festering resentments. Desperate families make the difficult decision to leave their historic homes and seek more stable places to live and work.

We see the consequences today in the heart-wrenching migration toward Europe from the Middle East and Africa that is, in turn, putting huge stress on the EU compact.

The consequences of climate change, from humanitarian crises to deeper regional instability or even overt conflicts, will inevitably preoccupy UN leadership.

Competition over water has been a constant throughout history. The diplomatic trick is to anticipate and keep these competitions from spilling over into violence.

Five water hot-spots jump to mind as potential—if not actual—caldrons of conflict: the Brahmaputra, Nile, Jordan, Tigris-Euphrates and Indus.

Although the bases for historic tensions differ from region to region, these are typically areas with on-going border disputes, religious and other fundamental differences, often unstable governance structures, and growing populations and therefore needs.

Some of the countries in conflict are nuclear powers (China and India who compete with Bangladesh and Bhutan for the waters of the Brahmaputra River Basin; Pakistan and India in the Indus). About 160 million people in 10 often unstable countries share the Nile River Basin. At any moment, the consequences of climate change could accelerate instability that could push any one of these regions into overt conflict.

While outgoing Secretary General Ban Ki Moon has made climate change a critical part of his mission, familiarity with the issue has not to date been part of the job description. But the consequences of climate change, from humanitarian crises to deeper regional instability or even overt conflicts, will inevitably preoccupy UN leadership as they did the calendar of Ban Ki-Moon.

It will not be the responsibility of the SG to negotiate climate agreements or carry out responsibilities assigned through those agreements; clearly those duties fall to the UN Framework Convention for Climate Change, the on-going body that is mobilizing 195 parties toward action on this existential threat.

But the SG can and should be leading the way to thread climate and its consequences into everything else the UN does. The SG needs the diplomatic skills to bring into this effort countries not entirely convinced of the urgency of climate change, and countries that may lack the skills and expertise to manage their carbon pollution or build climate resilient societies for the 21st century.

We know the pressures of climate change will inevitably be a significant part of security going forward. This was confirmed last week when President Obama directed the executive branch to weave climate change in to relevant national security doctrine, policies, and plans.

The selection of the new UN Secretary General should explicitly reference the cross cutting nature of climate. Understanding of this threat if not experience in its management should be explicitly considered in the selection process.

Wise leadership will explicitly incorporate climate change in to planning and action, anticipating future conflicts, preemptively if possible, and addressing current threats that, left unaddressed, can fester and grow.