It's not weather – it's climate disruption

Why can't we rally around a paradigm shift on energy policy? And why can't media get the story straight?

DALLAS – The climate-denying machine had scored yet another undeserved point in what has become a strangely combative and, quite frankly, unbalanced public debate over what most experts believe is now confirmed:

Specifically, our planet is under unsustainable stress and its recovery can only begin when public attitudes toward energy generation, consumption, and conservation advance.

The latest distraction came after researchers at George Mason University and the University of Texas at Austin found that only about half of the 571 television weathercasters surveyed believed that global warming was occurring and fewer than a third believed that climate change was caused "mostly by human activities."

I see in this the results of a carefully executed campaign by fossil fuel executives to dissuade the public appetite for energy reform. By shrewdly peddling deceptive information to confound and confuse the public's understanding of what is already a complicated subject, the intellectual exchange of ideas has been compromised, and Americans' tentativeness toward climate action has, regrettably, increased.

Perhaps the anti-climate science, anti-action, do-nothing insurgency preys on this quirky aspect of human nature.

Granted, there is a big difference between forecasting weather on the evening news and projecting long-term planetary conditions. But shouldn't we be trying to connect some dots?

Although the American Meteorological Society accepts climate change as real, their recommended undergraduate curriculum for broadcast meteorologists does not require a course on climate science, said National Wildlife Federation climate scientist Amanda Staudt. "Weathercasters often really do not have the academic background to speak as credible climate scientists."

So, what exactly do credible climate scientists know that the average local weather reporter and the average American may not? Data collected by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellite system inform our current understanding of just how climate change is affecting Earth. "GRACE uses gravity to measure mass changes in, among other things, the Greenland ice sheet," said Compton Tucker, senior earth scientist at the Goddard Space Flight Center. "It can track what the ice is doing day to day and month to month."

Since 2003, GRACE satellites have rotated around Earth 14 times a day, documenting a dramatic decrease in the volume of the Greenland ice sheet. The science is solid. "What amuses me," Compton said, "is that the sophistication of the GRACE system now consigns climate skeptics to the weird crowd that must confess to denying gravity!"

In other words, the same gravitational force that keeps Earth revolving in its orbit confirms what climate experts have been saying. "What we do know," remarked MIT Professor of Physical Oceanography, Carl Wunsch, who also studies GRACE's global measurements, "is that the changes in the Arctic are probably the most conspicuous indicators of the changes taking place in our climate system."

It's apparent from media coverage of the so-called "Climategate" e-mail release and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Himalaya glacier snafu that attitudes toward climate change have not kept pace with what leading climate scientists and physicists concur is largely undisputed science. "People are creatures of habit. It takes a big event to change behavior," said Cliff Davidson, founding director of Carnegie Mellon University's Center for Sustainable Engineering. "Although climate change is difficult to internalize, the large majority of professional papers written on climate change nevertheless agree that it is real, that it is happening, and that it is a threat." Davidson explained that the tendency of some media to balance each climate study with an oppositional viewpoint gives the impression that the science of climate change is uncertain. "It gives the public an easy excuse to not become invested in the problem," he added.

SueEllen Campbell, author and environmental literature professor at Colorado State University, agrees. Campbell cited a New Yorker column last summer by James Surowiecki entitled Status-Quo Anxiety.

In it, Surowiecki argues that people tend to want to hold onto what they already have, even when presented with something better. Surowiecki writes: "Our hesitancy to change is also driven by our aversion to loss. Behavioral economists have established that we feel the pain of losses more than we enjoy the pleasure of gains."

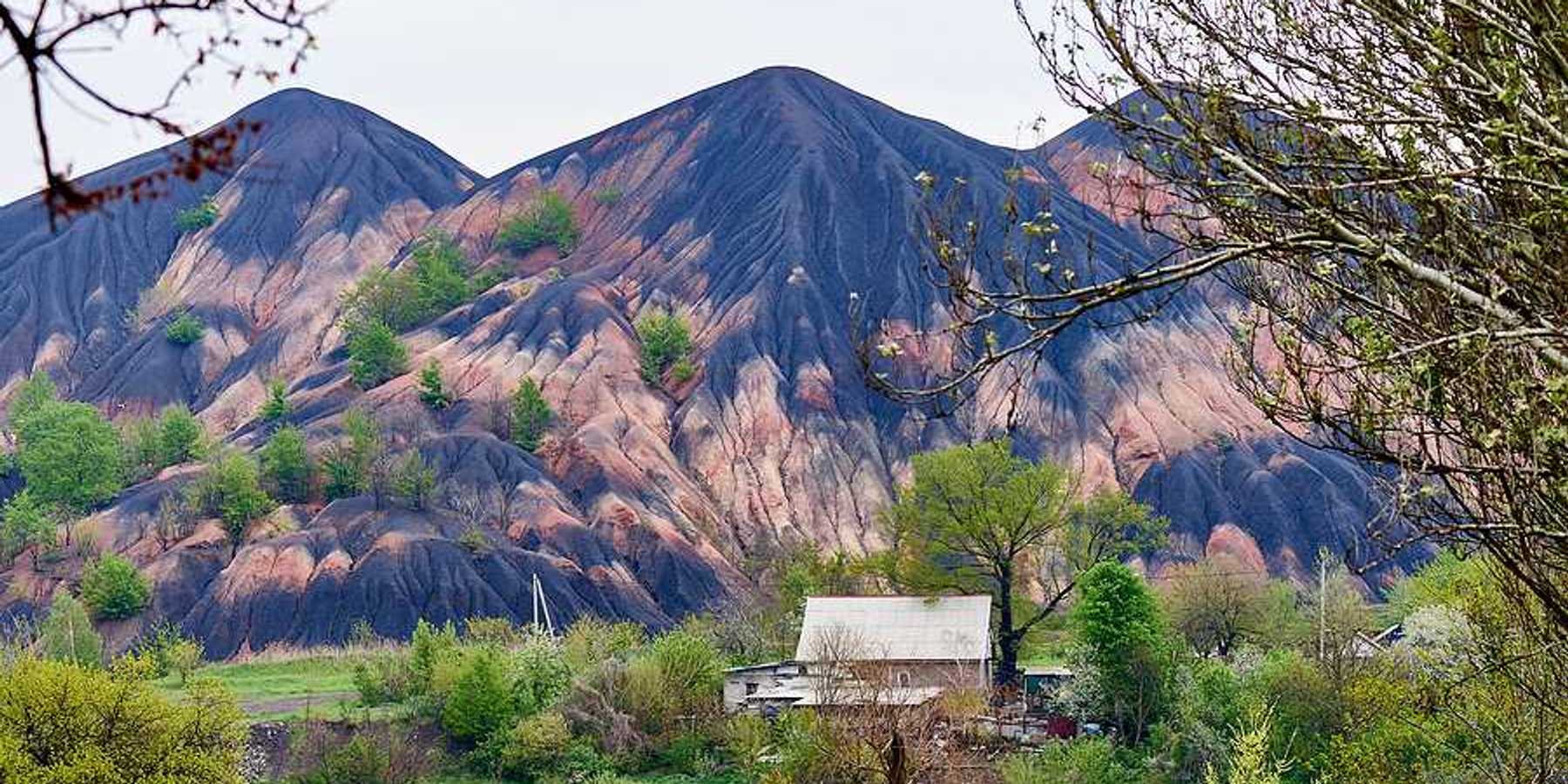

So perhaps the anti-climate science, anti-action, do-nothing insurgency preys on this quirky aspect of human nature. If status-quo defenders convince society that the lifestyle changes required to adapt to a changing climate will impart significant discomfort, they succeed at keeping modern society addicted to the bituminous fuels they wholesale. Simultaneously, and perhaps unintentionally, they script the eventual demise of contemporary human existence.

Robert Pollin, co-founder of the Political Economy Research Institute and a Professor of Economics at University of Massachusetts-Amherst enjoys challenging audiences to consider what he sees as the opportunities and benefits of adapting to a changing climate. At a recent gathering hosted by the American Enterprise Institute, Pollin opened with the following statement, "There are some outstanding researchers who think climate change presents such overwhelming ecological challenges for the next generation that we face the very non-trivial prospect of destroying life on Earth, and as an economist, an ecological disaster of this scale demands that we purchase insurance to guard against the risk."

It's not hard to see where Pollin is headed. By investing in alternative forms of energy now, Pollin argues that we can create more sustainable models for economic growth and prosperity. Mainstream media can take a valuable lesson from Pollin. If he can present change and adaptation in a positive light to a group of conservative-minded executives, imagine how his approach and experience could unleash society's innovative, problem-solving, adaptive skills. Perhaps the same community cohesion that unified American factory workers and volunteers during World War ll could be reignited to engineer, build, and install the renewable energy systems that will reduce our carbon footprint and lead to a more sustainable relationship with the planet.

How do we get there? For guidance I turn to my 14-year-old son. He can describe how electrons spontaneously jump to different energy levels on an atom; how black holes absorb light and bend time; and how radioactive elements can sterilize land for thousands of years. Of these issues, I know relatively little, but I welcome the perspective provided by a teen who easily communicates "big" concepts with ease and aplomb.

A teenager's ability to relate to science in relevant and meaningful ways is convincing evidence that reporters and news editors must at least be held to an equal standard. In covering the weathercaster story for the New York Times, reporter Leslie Kaufman made climate conflict the centerpiece of her discussion, rather than climate consensus. She buttressed her argument with a quote from Robert Henson, author of The Rough Guide to Climate Change (Penguin, 2008): "And the level of tension has really spiked in recent months." But when I called Henson, I received quite a different message: "There may be debate about localized issues like hurricanes," Henson said, "but the larger changes taking place are not debated.... These small-scale disagreements confuse people and the opponents take full advantage."

The key phrase is "small scale."

The science calls for a paradigm shift in energy policy. Americans must learn that energy reform delivers far-reaching benefits that easily outweigh the discomfort of adjusting to a new intellectual, behavioral and economic landscape.

Executives are starting to understand and articulate the rewards of this transition. We just need the media to get the story straight.

Stacy Clark is an environmental writer, activist and educator who lives in Texas. Contact her at DallasWriter.com. This story was originally published on April 19, 2010.