Mourning family and climate change in the age of loss and damage

Grief is a consequence of the natural cycle of life and death, but it can be exacerbated by negligence and unjust approaches to climate change.

The doctors told me that my mother’s hearing would be the last sense to go. My sister, a few close friends and I gathered around her hospital bed and sang “Amazing Grace,” tears rolling down our cheeks in disbelief.

That morning, I’d flown back to London from Geneva, Switzerland, where I was on a summer internship program, to ensure my nanay (Tagalog for mum), Lilila, was going to be okay. Though it had been a tumultuous year, I was convinced she would be fine. She’d been diagnosed with lung cancer the previous summer, though she had never smoked and barely drank. Then, a few months later, she was unexpectedly given the all-clear by the oncologist. My sister and I were relieved. On the plane back to London, I was still operating with the mindset that she was healthy, that her persistent exhaustion was normal, that soon we could all return to regular life.

By the time I arrived at the hospital, my mum wasn’t herself. She saw us, smiled, and quickly deteriorated as doctors tried to figure out what was going on. They were unable to and when she slipped away a few hours later, I was heartbroken, but also angry: with the doctors, but also with myself, at not being able to save her. Those feelings continue to this day, partly because it was never clear what happened to her. This anger complicates my memory of my mother. I wasn’t simply able to remember her as the kindest person I ever knew or the person who gave me the gifts I am most proud of; instead, her memory is darkened by the confusion of that day, the feeling of helplessness.

The experience of loss and grief after a traumatic event is hard to put into words. I’ve heard therapists and friends in London and New York, where I’m now based at Columbia University, attempt to find common ground with the feeling, and it never quite lands. I have felt anger, resentment and numbness. I have felt alone and misunderstood over the past few years as a consequence of my mum’s death. But it distresses me that I can’t name the cause of her death, that there is no tidy narrative or clear answers.

The inarticulable loss of my mum has also focused my research on the mental health impacts of climate-related disasters.

The death of my mother might not seem obviously connected to my job as a public health researcher, but the mourning caused by the losses from climate change are comparable to the ways in which losing a loved one feels. I’m not drawing any kind of equivalence between the grief and trauma of losing a parent and losing your entire life and livelihood after a disaster. Nevertheless, grief and feelings of loss permeate many experiences we go through. Whatever the source of grief and loss, my personal experiences have taught me that we need to process and accept these feelings for the sake of our mental and physical health.

This essay is also available in Spanish

Grief, defined one way as “keen mental suffering or distress over affliction or loss,” can be applied to the feeling after losing a loved one or losing a sense of home and place after a disaster. In both ways, we lose something we can never get back. Grief is a consequence of the natural cycle of life and death, but can be exacerbated by negligence and unjust approaches to climate change. And how we rebuild is also a function of the support network we have around us, as well as the resources we have and the timing of the events. But the resources we have to cope with grief are often dependent on circumstances outside of our control.

Once the headlines fade, climate change grief sets in

The author’s mother, Lilila Parks, with the author on a trip to the Philippines.

Credit: Robbie Parks

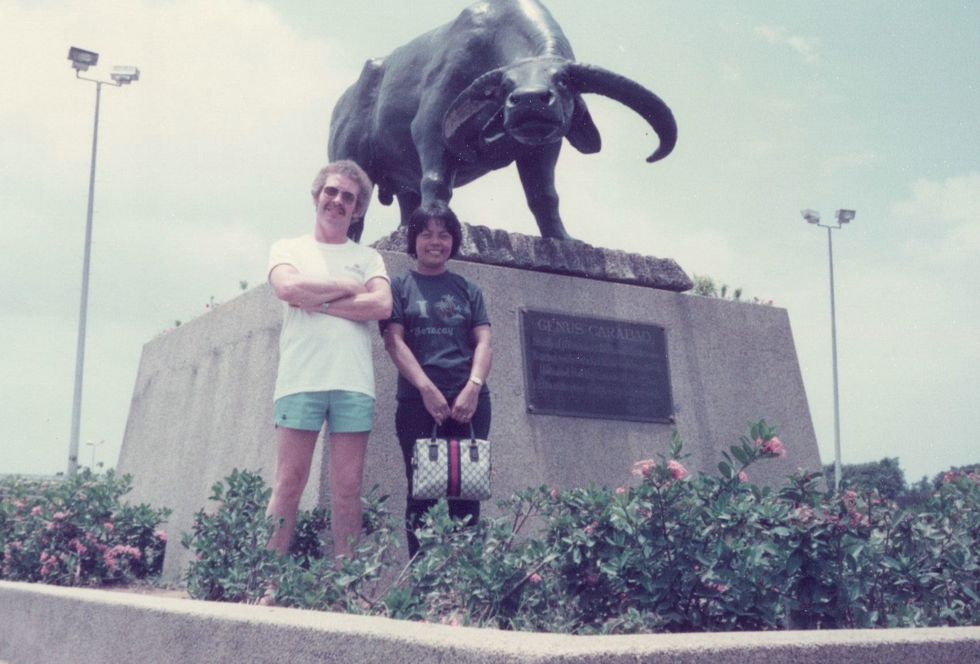

The author’s mother, Lilila Parks, and his father, Samuel Parks, on a trip to the Philippines

Credit: Robbie Parks

Though my mum didn’t die directly due to a climate disaster, she was undoubtedly impacted by her environment. Growing up, she experienced typhoons and floods on her home island of Negros. After she migrated to the UK from the Philippines, she worked as a domestic worker to provide for her children.

Climate-related disasters strike worldwide, with more than 200 million people impacted over the past two decades, and the acute and chronic impacts on physical and mental health can be devastating. This is only heightened in areas of the world where there are fewer resources to prepare before an event and rebuild in the aftermath of one. In the Philippines, Typhoon Haiyan in 2013 devastated communities and flattened parts of the country. Not only did thousands of people die, but millions more had their lives upended. For Typhoon Rai in 2021, many people are still living in temporary shelters, and many have lost lives. In the United States, whole communities never moved back to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and mold still impacts health in low-income housing in New York City after Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

For those of us not directly affected by such climate-related disasters, it is easy to move on once the headlines fade. But for those left behind, their entire lives as they knew it could be gone. You might lose your house or a loved one all at once, or your health might decline over the weeks, months or years after a disaster. Giving appropriate attention and funding to understanding disasters’ impacts on health, locally and worldwide, is critical to the fight for social, environmental and climate justice.

Climate-related disasters are unfortunately always going to happen, but we can mitigate the worst impacts with the right approach.

Grasping the true climate cost of Loss and Damage

A delegate outside COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt in 2022.

The author giving a talk at the New York Academy of Medicine.

What can be done to mitigate this grief and loss, to prevent this cycle of disaster and destruction from climate change? Solutions range from the local to the global. In New York City in the years after Hurricane Sandy, a network of emotional support was available via Project HOPE, involving individual counseling and public education. The Wildfire Recovery Fund in California supports mid- to long-term recovery efforts and provides mental health support. But post-disaster grief and loss is a worldwide phenomenon that requires coordination and cooperation.

Over the years and decades, the ideas of how to adapt to climate change have included commitments by rich countries to fund adaptation to fossil-fuel-free ways of life in poorer countries during the United Nations Climate Change Conferences and the Conference of Parties (COP). But until recently, there had been little discussion of how to fund recovery after climate-related disasters.

I was at the UN COP27 convention in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, in November 2022. A huge issue this time around was Loss and Damage, which can be understood as the harm generated from human-caused climate change, such as destroyed lives after climate-related disasters. But climate reparations, as the restitution for Loss and Damage has been called, requires a financial flow from the Global North to the Global South.

It was progress that a fund for Loss and Damage is now even being discussed. But there also needs to be solid finance behind the promises and intentions, as it remains unclear how the Loss and Damage fund will be filled. However, Mia Mottley, the Prime Minister of Barbados, is leading the call for reform of the global financial system via the Bridgetown Agenda.

What struck me in all of the discussions of Loss and Damage was precious little discussion of the lasting mental health-related impacts, including the sense of loss and place that is hard to restore if, for example, your family and home are gone. More recognition of the long-term impacts of grief in international frameworks is necessary. This will be the only way to get to a holistic adaptation and recovery possible as restorative climate justice. Still critically missing is a general recognition of the Loss and Damage to mental health and grief that climate change is having, and the necessary funding to even begin to address this. This is where the idea of personal grief from loss meets the need for climate-relevant investment.

Trying to rebuild after all is lost

The author’s mother, Lilila Parks, on a trip through Mambukal Hot Springs on Negros Island, the Philippines.

Credit: Robbie Parks

Losing my mum represents more than just losing a parent. My Filipino background feels lost with her passing too. I feel like I’m grasping at thin air with my culture and heritage. New people I meet, after learning that my mum was Filipina, usually can’t help but look a bit disappointed or confused when I explain that she never taught me Tagalog or Ilonggo, her regional language. Whenever I hear the few words I understand in Tagalog on the street, my instinct is to say “Kumusta!” (hello in English), but then I usually get tied up in my head, then say nothing at all. It is like the feeling of time and heritage slipping through my fingers, of being uprooted, with no true home.

At the time of my mum’s death, I was in the middle of my Ph.D., and was on an internship at the Joint Office for Climate and Health of the World Health Organization and the World Meteorological Organization. I was going to (finally) make her proud and pursue a life in academia. My parents had each moved to London from the Philippines and Glasgow, met while he was a barman and she was a chambermaid, and brought me up without means but with plenty of love in social housing in London. They dreamed big for me: they impressed upon me constantly the importance of academic excellence, despite them not really knowing what education looked like beyond high school. This became even more important especially after losing my dad in my teenage years. Now sometimes all I feel left with are ghosts of memories. But that’s still more than enough to keep me wanting to make them proud.

It's now been several years since my mother’s passing. Many well-meaning friends and family told me that the grief would pass. Initially I thought I was missing out on some secret cure to the grief, or that not enough time had passed. However, after further thought and reading, including “The Myth of Closure: Ambiguous Loss in a Time of Pandemic and Change” by Pauline Boss, I now understand that what I was experiencing was normal: The grief never goes away, but as a person you learn to grow and carry it with you.

Hearing “Amazing Grace” still takes me back to watching my mum’s final moments. Now, when I think about my parents, though I still get a little sad, I more try to focus on how they might be proud that their son managed to build on their hard work. I have chosen to contribute to the conversation around climate change and public health to honor my family, my grief and loss, and my heritage.

Robbie M. Parks is an assistant professor in environmental health sciences at Columbia University, an NIH NIEHS K99/R00 fellow at Columbia University, and lead instructor of the SHARP Workshop on Bayesian Modeling for Environmental Health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

This essay was produced through the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice fellowship. Agents of Change empowers emerging leaders from historically excluded backgrounds in science and academia to reimagine solutions for a just and healthy planet.