Opinion: When kids feel the magic of nature, they will want to protect it

Improving our quality of life starts with the simple of act of getting kids outdoors.

When people think of environmental activism and health, we often think of shaping policies: protecting groundwater from over-pumping; halting strip-mining and clearcutting; removing dams from salmon streams.

However, one important element of environmental health often gets missed: kids’ relationship with the natural world. This is why early childhood outdoor-based environmental education must play a larger role in the national environmental conversation, and environmental education programs must be significantly expanded and strengthened throughout the U.S.

One of the most important responsibilities that adults have is to connect our children to the natural world. As a lifelong environmentalist and outdoors person, I see few more essential tasks than helping young students acquire a sense of wonder that can infuse their entire life and to feel a connection to nature so strong that they will become the next generation of conservation-minded citizens. This serves both the students — giving them access to the physical, emotional and professional benefits of time outdoors — and society, which needs environmental advocates now more than ever.

Environmental values

Environmental progress starts with peoples’ values, that is, what people consider important, what they want to protect. Some adults have an ecological awakening later in life — maybe they read a story of drying wells or heard gossip about the “forever chemicals” in their municipal water supply. Some of us develop environmental values in college, after peers go vegetarian or our professors introduce us to concepts like environmental injustice. But kids can develop these values much earlier, starting at home and in the classroom.

The idea of showing kids the value of protecting nature before they ever start high school isn’t political indoctrination or aimed at creating the next generation of Greenpeace activists. It’s about building a personal connection with the natural world — and it starts with going outside.

Feel first, teach second

“A child’s world is fresh and new and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement." — Rachel Carson, “The Sense of Wonder”

Credit: Aaron Gilbreath

No matter the curriculum or setting, part of my teaching as an unofficial educator comes from scientist Rachel Carson’s book “The Sense of Wonder.” “A child’s world is fresh and new and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement,” Carson writes. “It is our misfortune that for most of us that clear-eyed vision, that true instinct for what is beautiful and awe-inspiring, is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood.”

"One of the most important responsibilities that adults have is to connect our children to the natural world."

How do we help children develop this sense of wonder? Through parents, mentors and educators in programs like the World Salmon Council and Ecology in Classrooms and Outdoors in Oregon, Sierra Nevada Journeys in California and the National Wildlife Federation’s EcoSchools U.S. program, to name a few. Richard Louv’s Children and Nature Network might be the most formalized, vocal advocates trying to green children’s lives. Carson knew it takes just one person to build this bond. “If a child is to keep their inborn sense of wonder,” she wrote, “they need the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with them the joy, excitement, and mystery of the world we live in.”

As the world becomes more urbanized, fewer children have the chance to regularly interact with wildlife and the non-built environment.

Credit: Aaron Gilbreath

Carson’s approach: Take them outdoors. Discover together. Let them see what excites you. Get excited and share those feelings. Focus on the emotional experience first — the wow factor — not what information you have, she writes. Feel first, teach second. Don’t worry if you don’t have nature facts. “Adopt the child’s position,” Carson advises. Instead of being their teacher, she suggests we discover new things and feel awe with them. A single residential block can seem like a universe to a young mind and you can provide this transformative experience in your front yard as easily as you can in a wild stream in a federal wilderness area. Just look up at the clouds. Search bushes for insects. Point to the moon and the birds and literally stop and smell whatever flowers you walk past. “The sharing,” Carson writes, “is based on having fun together rather than on teaching.”

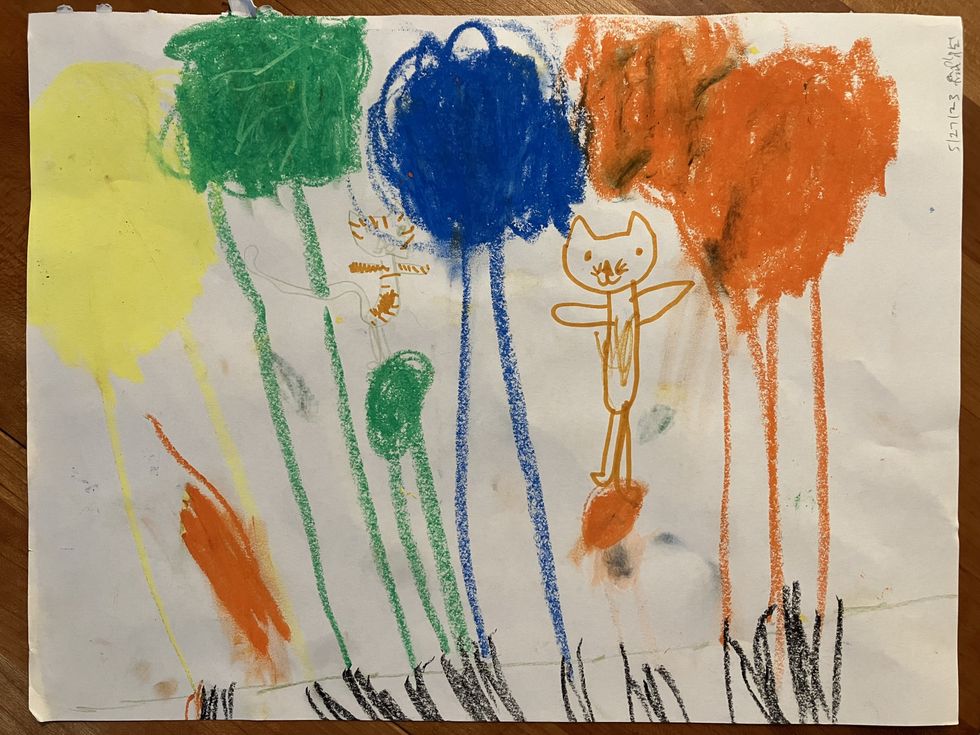

Ever since my daughter was born, I’ve spent a great deal of time showing her the outdoors, from our Portland, Oregon, backyard to the Northwest forests to the Sonoran Desert where I grew up. This summer she held wild spotted toads and giant desert millipedes in Arizona. Last month she held tree frogs while standing in knee-deep water on the banks of the Deschutes River. At age six, she has come to love wildlife so much she kissed a banana slug she found at Hoyt Arboretum and asked how old you have to be to work at the zoo. Green is her favorite color. She rattles off animal facts everywhere she goes and she always makes sure to rescue insects that get trapped in pools or indoors. She is curious, empathetic and always asking questions. Most of all, she is comfortable outdoors.

Not to toot my own horn, but in a qualitative way, her multifaceted worldview is the clear, direct result of my homegrown nature education that combines hands-on experiences, shared excitement and scientific information. It’s all about Carson’s approach: cultivating wonder and curiosity and complementing it with teaching. I believe this perspective will benefit her for her entire life. I only wish her public school had the resources to offer her similar outdoor education as part of the curriculum.

Combatting nature deficit disorder

An increasing body of research shows how time outdoors rejuvenates us, reduces stress, improves creativity, enhances our immune systems and improves our moods.

Credit: Aaron Gilbreath

Another reason outdoor-based education is so important is because it fundamentally involves the act of going outdoors. As the world becomes more urbanized, fewer children have the chance to regularly interact with wildlife and the non-built environment. Too many under-resourced American kids never get that chance. The forces driving a wedge between children and the natural world multiply every generation: screens, phones, social media, urbanization, anxiety, concerns about public safety, exhausted working parents. The average American spends 93% of their time indoors.

In 2008, more people lived in cities than outside of them for the first time in history, officially making Homo sapiens an urban species. And the trend is accelerating. “By 2050,” Science reported, “66% of the world’s population is projected to live in cities.” That doesn’t mean city life is good for us. According to sociobiologist E.O. Wilson, human beings’ nervous systems evolved in nature, so we are more used to — and more comfortable in — non-human environments than we are in urban environments. Outdoor education is the crucial bridge that connects us back to our recent evolutionary past.

The physical and emotional effects of what author Richard Louv calls “nature-deficit disorder” are numerous, but the flipside is that time outdoors provides quantifiable benefits.

An increasing body of research shows how time outdoors rejuvenates us, reduces stress, improves creativity, enhances our immune systems and improves our moods.

It’s hard to speak about the value of something as ethereal as wonder, because you can’t provide a value proposition if you don’t have data to support it. Wonder — how do you measure it? But anyone who has improved their own emotional and physical health by spending more time outdoors can recognize the value of providing that experience to America’s increasingly sedentary, domestic youth. If the thought-leaders and activists who work so hard to strengthen our country’s environmental policy want to continue doing the work that benefits the greatest good, we must discuss the role of early childhood environmental education.

"Ever since my daughter was born, I’ve spent a great deal of time showing her the outdoors, from our Portland, Oregon, backyard to the Northwest forests to the Sonoran Desert where I grew up. I believe this perspective will benefit her for her entire life."

Credit: Aaron Gilbreath