Kids with asthma who live near heavy air pollution face greater risk from coronavirus

"There's a lot of concern about combined effects of air pollution and respiratory viruses."

PITTSBURGH—Kids who have asthma and live near industrial polluters may face higher risk from novel coronavirus and its resulting disease COVID-19 in the coming months.

COVID-19 is a respiratory disease that has infected people in all corners of the globe. As of today, more than 216,000 Americans have tested positive for the disease and 5,137 have died.

So far, children have contracted coronavirus at far lower rates than adults, and fewer children have been hospitalized with severe symptoms. But that doesn't mean they're immune—a 12-year-old, a 14-year-old, and an infant have been among those killed by the virus in recent weeks.

Having asthma makes it more likely that someone who contracts the virus will experience more serious symptoms, including difficulty breathing and acute respiratory disease requiring hospitalization. And research suggests that ongoing exposure to air pollution compounds both of those risk factors.

"People with asthma have airway inflammation and swelling, so their bodies are already primed to react to anything that's out in the environment, including respiratory viruses," Dr. Deborah Gentile, a pediatric asthma and immunology specialist and former director of clinical research in the Division of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology at Allegheny Health Network in Pittsburgh, told EHN.

"There's a lot of concern about synergistic or combined effects of air pollution and respiratory viruses," she added. "Some literature shows that respiratory viruses and air pollution can work together to cause more and worse forms of disease when combined. So if you have asthma at a level of two and you're exposed to air pollution at a level of two, and a respiratory virus at a level of two, it won't add up to a risk factor of just six—it's more like eight or 10."

This means that children faced with all three—asthma, air pollution exposure, and coronavirus— are likely to experience more wheezing and difficulty breathing and to require hospitalization.

Long-term exposure to air pollution could make the virus more deadly. Gentile pointed to research conducted after China's 2002 SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) pandemic, which revealed that people living near sources of industrial air pollution who contracted the disease were nearly twice as likely to die from it.

"Coronavirus isn't SARS," she said, "but it is similar enough to be considered a 'sister virus,' so we have serious concerns for anyone with underlying respiratory conditions who is living near an air pollution source—especially if their disease isn't well controlled."

Meanwhile, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced last week that it would allow companies to break pollution laws without penalties during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, prompting widespread concern among public health experts.

Having poorly controlled asthma means requiring the use of a rescue medication like an inhaler more than twice a week. It's especially critical to ensure that kids with asthma have their disease under control right now, since a trip to the emergency room could mean additional risk of exposure to coronavirus, and would divert critical health care staff and resources away from caring for COVID-19 patients.

Gentile also noted that one of two annual asthma peaks for the eastern U.S. is just around the corner.

The biggest peak is usually in the fall, when pollen season is still causing allergies and kids going back to school start spreading respiratory viruses. Asthma rates tend to fall in the winter, then a second, smaller peak usually occurs in April and May.

"The most common outdoor allergy is actually grass," Gentile explained. "About 80 percent of children with asthma have underlying allergies, whereas in adults it's only about 50 percent, so asthmatic children with underlying allergies who are going into spring allergy season are at even greater risk during these months."

On the front lines of air pollution

Erica Butler of the Pediatric Alliance administers an asthma screening to Montaziyah Evans at Clairton Elementary School in Clairton, PA. (Credit: Connor Mulvaney/EHN)

A few years ago, Gentile conducted research in Pittsburgh, a region that continues to struggle with poor air quality, and found that around 22 percent of children in school districts near industrial sources of air pollution have asthma—more than double the national average of 8 percent.

The research also showed that asthma is poorly controlled in 60 percent of children with asthma in Pittsburgh's most polluted neighborhoods, compared to a national average of 38 percent.

One school district with unusually high rates of uncontrolled childhood asthma is in Clairton, 15 miles south of downtown Pittsburgh. The elementary school sits on the fenceline of U.S. Steel's Clairton Coke Works plant, which is the nation's largest manufacturer of coke (a key material in steel manufacturing), and one of the biggest sources of air pollution in the state of Pennsylvania.

Clairton and the surrounding regions regularly see some of the worst air quality in the country as a direct result of emissions from Clairton Coke Works, which has been subject to numerous fines and lawsuits over its frequent violations of the Clean Air Act.

The facility was exempt from the statewide order to close all "non life-sustaining" businesses in order to slow the spread of coronavirus. It has remained open, requiring employees to come in even if someone in their household had been exposed to the virus or was told to self-isolate by their doctor, according to a report from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Last Thursday, the region surrounding the Clairton Coke Works had a "code orange" air quality day—meaning outdoor air is unsafe to breathe for those with asthma and other respiratory conditions.

"On a code orange day, children should not be playing outside," Gentile said. "That's especially true for kids with asthma, but all children breathe more air in and out of their lungs and get a higher proportion of harmful pollution exposure than adults do on an orange day, especially if they're running around playing and exercising."

The air pollution event prompted local environmental and community health advocacy groups to urge U.S. Steel to voluntarily reduce emissions to help further protect workers and residents from coronavirus.

U.S. Steel has not indicated any plans to voluntarily reduce emissions, but has opted to delay several construction projects aimed at reducing emissions and improving efficiency at facilities throughout the Pittsburgh region, including Clairton Coke Works, "until market conditions become more certain," President and CEO David Burritt said in a statement.

There is some good news for the region: In response to the EPA's plan to stop enforcing environmental regulations, the Allegheny County Health Department, which oversees local air quality locally, announced that it will continue enforcing clean air standards in the Pittsburgh region as usual.

"Air quality in our region...continues to be one of our most pressing public health challenges," said Dr. Debra Bogen, the recently-hired Director of the Health Department, in a statement. "Even during this pandemic, with our attention focused on response and actions to deal with COVID-19 in our community, we are not losing sight of that need."

How parents can keep asthmatic kids safe

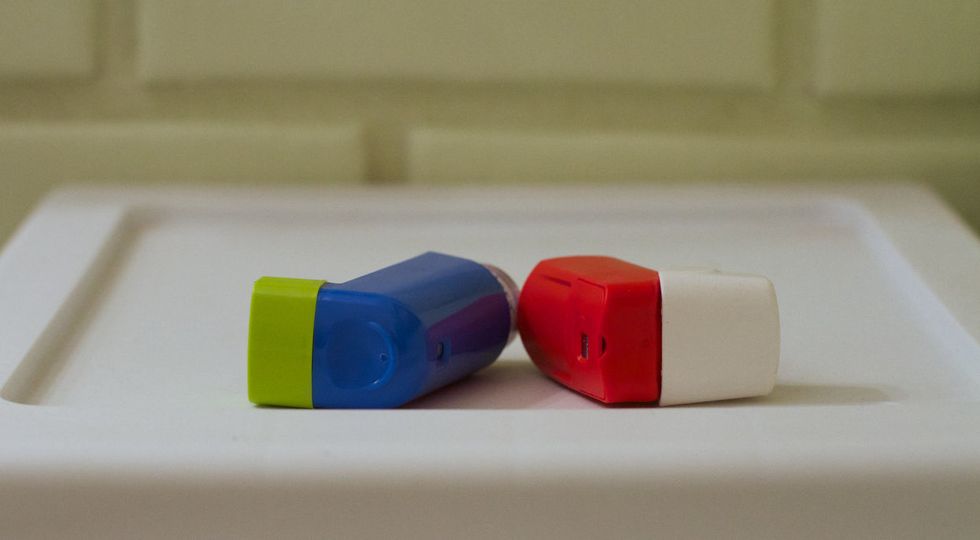

Health experts say as the coronavirus continues to impact healthcare facilities parents should make sure kids have asthma medication on hand. (Alan Levine/flickr)

Dr. Franziska Rosser, a pediatric pulmonologist and researcher at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center's Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, told EHN that now is an ideal time for parents of asthmatic children to touch base with their doctors.

"If kids with asthma haven't had a doctor's appointment in several months, or if parents have any concerns that their asthma isn't well controlled, they should call their child's doctor," she said. "Healthcare providers can do a lot over the phone to make sure their asthma is well controlled on a daily basis and that they have a plan in the event of a flare-up."

She also suggested that parents brush up on how to properly use inhalers, nebulizers, and spacers (a plastic canister attachment that holds medicine sprayed from an inhaler in place so it is easier to inhale) and make sure their kids are following all the right steps, since improper use can mean that less medication is reaching the lungs.

Gentile said parents should make sure they have plenty of their kids' asthma medication on hand. She said she sometimes prescribes emergency anti-inflammatory medications for patients who are especially prone to severe asthma attacks to keep at home, so that if a rescue inhaler isn't working well, they have another option before resorting to the emergency room.

"Obviously if it's a severe asthma attack where someone's lips are turning blue or they're going to pass out, call 9-1-1," she added. "But for people just having a less severe increase in symptoms, we'd like to keep them out of the ER or urgent care as much as possible throughout the pandemic."

Spring allergies will also make kids (and adults) more likely to touch their faces if their noses are running or their eyes are itchy. Face touching can spread the virus, so frequent hand washing with soap for at least 20 seconds will be extra critical as allergies begin to flare.

Both Rosser and Gentile noted that while it's best to keep asthmatic kids indoors and close the windows on poor air quality days and days when kids are experiencing allergic reactions to grass or pollen, it's critical for parents who smoke—and are now home during the day—to do so outside, away from their child.

Other sources of indoor air pollutants that can trigger asthma exacerbations include air fresheners, scented plugins, and candles.

"Those things are very irritating to patients with allergies and asthma," Gentile said, "so while you're spending all this time indoors at home, make sure to avoid those exposures." She added that it's also best to keep asthmatic kids away from outdoor wood fires or bonfires.

Stress can also be a trigger for asthma exacerbation, Rosser said, "So during this stressful period, it's important that parents take time for self-care, and time to focus on the emotional health of their kids, too."