Bioplastics: sustainable solution or distraction from the plastic waste crisis?

Biodegradable and plant-based plastics are booming — but still come with climate and chemical concerns.

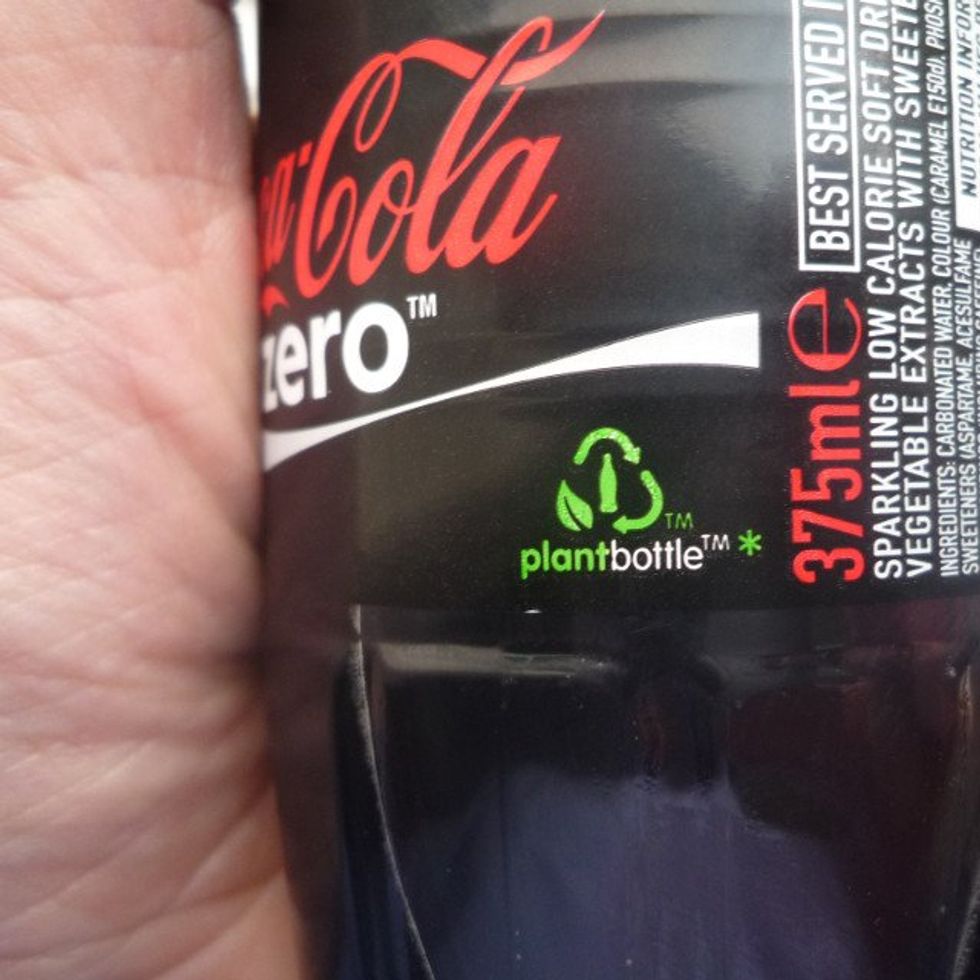

From Chipotle’s compostable burrito bowls to Coca Cola’s plant-based bottles to supermarkets’ opaque produce bags, bioplastics are proliferating across the food industry.

And not just there: they are cropping up in car cushions, electronics, clothing, building supplies and more.

Bioplastics are defined as plastic materials that are either partly or wholly derived from renewable biomass like plants or are biodegradable or are both. The global bioplastics industry is booming: it’s projected to grow from $8.7 billion in 2023 to $31 billion by 2030 – a growth rate faster than the traditional plastics industry.

Though bioplastics comprise just 1% of the plastics market, some tout them as plastics’ more sustainable future. As delegates prepare for the next round of global treaty talks to tackle plastic pollution in April, some are angling to include bioplastics as alternatives and substitutes in the treaty.

“Bioplastics are driving the evolution of plastics,” the European Bioplastics Association claims on its website, citing “carbon neutrality” and biodegradability (in some cases) as bioplastics’ advantages over their conventional counterparts. But they fail to mention that bioplastics haven’t fully lived up to the hype of faster decomposition rates, safer materials and smaller carbon footprints. Still, experts say the material could be among a suite of solutions if end-of-life management and chemical safety were factored into their design, and stronger standards and regulations were put in place to prevent companies from greenwashing their materials.

“Bio-based plastics can be part of the solution, if—and that's a big if—we manage to make them safe,” which includes ridding them of chemicals of concern and producing them in way that doesn’t create a lot of nano- and micro-plastics, Martin Wagner, associate professor in biology at the Norwegian Institute of Science and Technology, told Environmental Health News (EHN).

Wagner’s research has found that those seemingly Earth-friendly compostable bowls and plant-based soda bottles could be leaching chemicals that are as harmful to our health as those found in traditional plastics. Moreover, biodegradable bioplastics don’t resolve the plastics waste crisis. They must be properly managed at the end of their life, but we don’t yet have the industrial composting infrastructure or the regulatory safeguards in place to manage bioplastic waste.

That’s why scientists and advocates say that using less plastic is the most important solution to the plastics crisis. They worry that single-use bioplastics are a distraction.

“If you're extracting from the Earth and manufacturing something a bajillion times just to be used once and thrown away, that's really where the problem is,” Crystal Driesbach, executive director the reuse advocacy group Upstream, told EHN.

Bioplastics: A confusing catchall

The lack of clarity on terms such as biodegradable or bio-based leads to a lot of misunderstanding.

“If I look at it with a cynical hat on, I think [bioplastics] is a term that was deliberately created to manifest confusion,” Richard Thompson, professor of marine biology and director of Plymouth University’s Marine Institute, told EHN.

Many mistakenly believe that all bioplastics are biodegrade or break down in the environment. Many also assume that bioplastics means plant-based, but some, like polybutylene adipate terephthalate, or PBAT, are solely made from fossil fuels. The industry calls materials like PBAT bioplastics because they have been engineered to break down just as plant-based bioplastics do, depending on the type of chemical bonds in them and environmental conditions.

“Bio-based plastics can be part of the solution, if—and that's a big if—we manage to make them safe.” - Martin Wagner, Norwegian Institute of Science and Technology

Industry groups bioplastics into two camps: biodegradable or not, often lumping together plant-based and fossil fuel-based plastics in each category. Global production is closely split between these two camps.

Compostable bioplastics are a subset of biodegradable bioplastics that can fully decompose within 12 weeks at an industrial composting facility, according to industry standards. Meanwhile, non-biodegradable bioplastics include bio-based polyethylene (bio-PE), biobased polyethylene terephthalate (bio-PET) and polyamides ( nylons). These bioplastics have been engineered to function exactly as traditional plastics, even though they’re derived from sugarcane, sugar beet, molasses or corn.

The most common biodegradable bioplastic is polylactic acid, or PLA, which is made from a polyester derived from starches, typically corn. Cellulose-based bioplastic fibers also fall into this category, as do bioplastics made from polyhydroxyalkanaota (PHA) and polybutylene succinate, (PBS), which are derived from agricultural byproducts, algae, yeasts and bacteria, and considered more sustainable.

So-called “third generation” bioplastics made from feedstocks –including agricultural wastes, food waste, kelp, algae, switch grass, waste oils, bacteria, and wood waste– are emerging and are considered more sustainable because they’re not made from food crops. Some products are already on the market, but they have not reached the scale of products made from PLA or bio-polyamides.

What products are bioplastics in?

Single-use bioplastic beverage containers, compostable food service ware, retail packaging, and other food industry products comprise 43% of bioplastics use, Heather Nortz, manager of sustainability at the Plastics Industry Association, told EHN. PLA and bio-PET are the most used.

Biodegradable mulch films and other agricultural products, made largely from PLA and PHA, make up 21% of use, while consumer goods, including glasses, textiles, cups, iPhone cases and coffee pods, comprise 13%, according to Nortz. These goods are made from a variety of bioplastics, both biodegradable and not.

The automotive industry is another big user. Car cushions, dashboards, bumpers, battery covers and other parts are increasingly builtfrom bio-based polyamides and bio-PP. Bioplastics are also used to a lesser extent in the building and construction, electronics and coating industries.

The biggest bioplastic manufacturers are divisions within, or spinoffs from, petrochemical giants producing fossil-fuel plastics. Financial analysts, however, don’t agree on which ones are leading the pack. Insider Monkey, for example, ranks BASF SE, Dow Inc., LyondellBasell Industries, LG Chemical and Celanese as the top five manufacturers based on their overall market capitalization, even though bioplastics are a small part of that. Other analysts list companies that have been acquired by, or are joint ventures with, petrochemical companies as market leaders, including Corbion, Biome Bioplastics, Plantic, NatureWorks and PTT MCC Biochem.

Environmental and health challenges

Bioplastics are made using the same processes as traditional plastics. Polymers are stitched together from chemicals extracted at least partially from plant materials, and in some cases entirely from fossil fuels. Chemical fillers, additives and dyes are added to confer flexibility, durability, color and other properties.

Bioplastics, therefore, can still harbor toxic chemicals, Erin Simon, vice president and head of plastic waste and business at WWF, told EHN. “If you're making PET, you're either making it out of old carbon or new carbon. You’re making the same thing, in the end, so a lot of processing chemicals are still there.”

Wagner’s 2020 study found that 43 everyday bioplastic products made from PLA, PBAT, PHA, PBS, bio-PE and bio-PET, were just as toxic as its conventional counterparts. Two-thirds of the samples were able to harm a wide range of organisms in the environment. Forty-two percent induced oxidative stress, which measures a chemical’s ability to create DNA-damaging free radicals. Just under a quarter showed hormone-disruption properties.

Individual bioplastic samples contained a staggering 1,000 chemical features on average and as many as 20,965. “The most striking for me when we do this type of research is that we get the immense number of chemicals in an individual plastic product,” said Wagner, the study’s author.

A 2020 study found that 43 everyday bioplastic products made from PLA, PBAT, PHA, PBS, bio-PE and bio-PET, were just as toxic as its conventional counterparts.

While the study didn’t identify most detected chemicals, Wagner noted that they didn’t find the “usual suspects,” like phthalates. “We know even less about the type of chemicals that are used to make bioplastics functional... it might be a different set of additives because the polymer chemistry is different,” he said.

Bioplastics and climate change

A common argument in support of bioplastics is that, in theory, they produce far fewer greenhouse gas emissions than traditional plastics over their lifetime because there is no net increase in carbon dioxide emissions when carbon is extracted from a renewable plant source.

The European Bioplastics Association, for example, claims that substituting the annual global demand for fossil-based polyethylene with bio-PE would prevent more than 80 million tons of carbon dioxide from being emitted – the equivalent of 20 million flights– every year. A 2017 study estimated that switching from traditional plastic to corn-based PLA would cut U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 25%. Greater emissions reductions could be achieved if the chemical industry switched to renewable energy and advanced feedstocks like switchgrass, the paper stated.

Individual bioplastic samples contained a staggering 1,000 chemical features on average and as many as 20,965.

In contrast, reusable containers made from ceramics, stainless steel and glass produce three to 10 times less carbon dioxide emissions than single use bioplastics over their lifetimes, Dreisbach said.

Bioplastics’ significant carbon benefit is also counterbalanced by increased use of fertilizers and pesticides and forest burning to clear land for, say, corn or sugarcane production. Moreover, when biodegradable plastics end up in landfills, as they often do, they emit the potent greenhouse gas methane as they break down.

Bioplastic waste

Waste management is a thorny challenge for biodegradable bioplastics, in part because there are no regulations defining biodegradability. While a voluntary industry standard specifies that 90% of a biodegradable product must break down in the environment within six months, some products labeled biodegradable can take years to disintegrate. One study found that biodegradable plastic bags were still fully intact after three years of being buried in soil. If such materials land in a compost facility, they become a contaminant that needs to be screened out.

Recycling facilities don’t want those wastes either because they can compromise a whole batch of recycled plastic, Thompson said. And because many municipalities do not have industrial composting facilities or curbside collection, a lot of compostable packaging and carryout containers end up in a landfill or incinerator.

Poor labeling adds to the confusion, as non-compostable plastics are often mistaken for compostable versions. Linda Norris Waldt, deputy director at the U.S. Composting Council, calls such materials “greenwashed, look-alikes and tagalongs.” Composters don’t want to take compostable food packaging because of such materials, which cut into their profitability.

“Number one, it's a labor issue and number two, it's degrading the end-product so much that it's affecting our markets, whether it's farms, landscapers, or golf courses,” Norris Waldt said. Bioplastics can contaminate compost with chemicals and microplastics that may harm the life in soil and possibly concentrate in the food chain ecotoxic effects.

Even so, a majority (71%) of industrial composters surveyed by Biocycle last year said that they accept some forms of compostable food packaging, such as packaging that is certified compostable by the Biodegradable Institute, BPI, or its European counterpart, OK Compost. To certify their products, bioplastics manufacturers must meet ASTM criteria for how quickly their product breaks down, as well as be PFAS-free and pass a general soil ecotoxicity test. These certifications don’t account for microplastics, however, which is a growing composter concern, Norris Waldt said.

Opportunities for innovation

Despite these challenges, bioplastics may be suitable alternatives for limited applications, such as agricultural mulch film, experts say, particularly if chemical safety and end-of-life are factored into their design.

“In the cases where plastics are essential, we're going to want them to be biobased,” Mark Rossi, executive director of Clean Production Action, told EHN. “Every material is going to have its issues. How do you optimize those materials from a human health and safety perspective?”

The plastics industry sees bioplastics as a growth opportunity in certain markets., but not as a replacement “Bioplastics are not a replacement for plastics on a large scale, Nortz said.

Newer generation bioplastics made from kelp or agricultural wastes resolve some of the environmental challenges associated with deriving feedstock from food crops, but they still need to address toxicity concerns.

To guide manufacturers in screening out thousands of harmful chemicals from their products, Clean Production Action developed third-party audited standards for single-use food packaging and reusable containers, called GreenScreen. One major manufacturer of PLA, Natureworks, has certified through GreenScreen that its raw materials don’t contain harmful chemicals. But to shift the industry, many more manufacturers need to certify their products.

“In the cases where plastics are essential, we're going to want them to be biobased." - Mark Rossi, executive director of Clean Production Action

Ultimately, stronger labeling standards and laws – like those passed in California and Colorado–are needed to ensure that truly compostable bioplastics are sent to industrial composters, Norris Waldt told EHN.

“A few lawsuits from flagrant [companies] who are either inadvertently or purposefully mislabeling your cereal as compostable, will stop [mislabeling] pretty quick. Enforcement is the key,” she said.

On a global scale, experts agree while bioplastics certainly have a place in the global agreement to stem plastic pollution currently being hammered, these materials should be handled no differently than traditional plastics.

“We don't just need alternatives and substitutes,” Thompson said. “We need alternatives and substitutes that are proven to perform better than the problem we're trying to fix.”

The Scientists Coalition for an Effective Global Plastics Treaty, an international group Thompson and Wagner belong to, would like the treaty to include incentives for redesigning plastics to contain fewer chemicals and creating simplicity in materials recovery.

“We really want the industry to design products that do not contain 10,000 chemicals,” Wagner said.