Houston area has more than 100 unauthorized air pollution events already this year

An EHN analysis finds nearly half were related to flaring.

HOUSTON — It was just after noon on August 26, 2024, when Shiv Srivastava recorded the skyline of Houston’s East End while an industrial flare from TPC Group roared in the distance after power loss.

Srivastava is the policy director at Fenceline Watch, an environmental nonprofit based in Houston’s East End. As the cloud of black smoke expanded over the downtown skyline, he worked with Yvette Arellano, Fenceline Watch’s executive director, to research air quality updates to share with community members on social media. It was not the first time they responded to air pollution problems like this one.

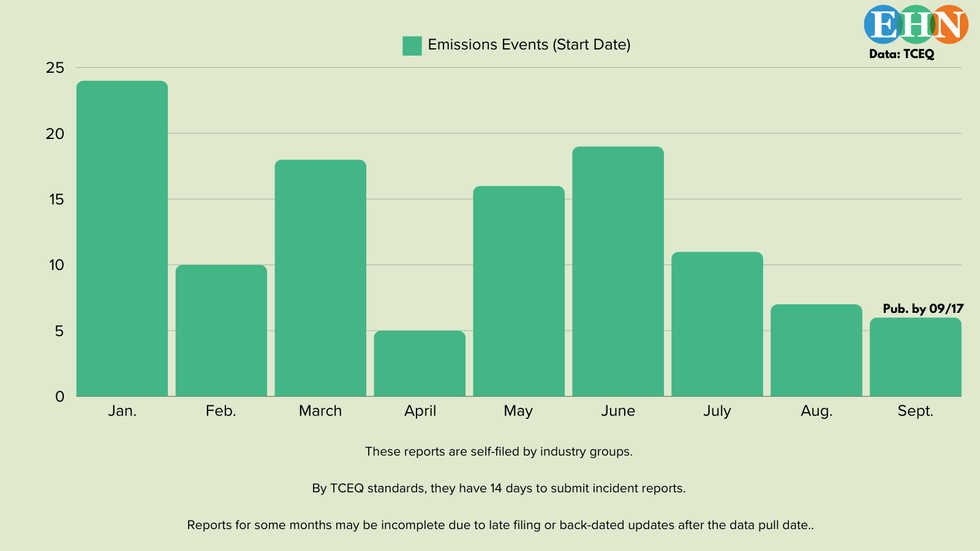

Unauthorized emissions — any air pollution released from industrial plants beyond permitted levels — occur once every 2.5 days on average in Harris County, which encompasses Houston, according to 2024 the data from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. EHN analyzed 116 emissions event reports from a Commission database published from the beginning of this year to September 17, 2024. Once an emissions event starts, the facility is required to submit a report to the database if the expected emissions are above a reportable quantity that varies by pollutant. Final reports are required within two weeks of the completion of an event, which can either last minutes with emissions below reportable levels, or days, releasing thousands of pounds of often toxic chemicals. Compounds released in these events can range from climate-warming methane to volatile organic compounds that increase cancer risks, like benzene or 1-3 butadiene.

Most of these emissions concentrate around the Houston Ship Channel. At 52 miles long, the channel intersects with many communities and 16 of those miles span across Harris County. The channel is home to roughly 600 petrochemical facilities, many of which are emitting hazardous air pollutants from their authorized permits. In addition to these millions of pounds of harmful authorized emissions, the unauthorized emissions events increase communities’ pollution burden.

“There is a toxic load our communities are forced to face,” Srivastava told EHN. “Unfortunately, you have regularity of flaring events, a lack of transparency for community members…a lack of follow up both with local officials and community members and a media structure that also minimizes and normalizes it. That leads to a very dangerous framework that our communities are forced to live in.”

Repeat air pollution offenders

Night view of the industries along the Houston Ship Channel, taken in 2018.

Credit: 2C2K Photography/Flickr

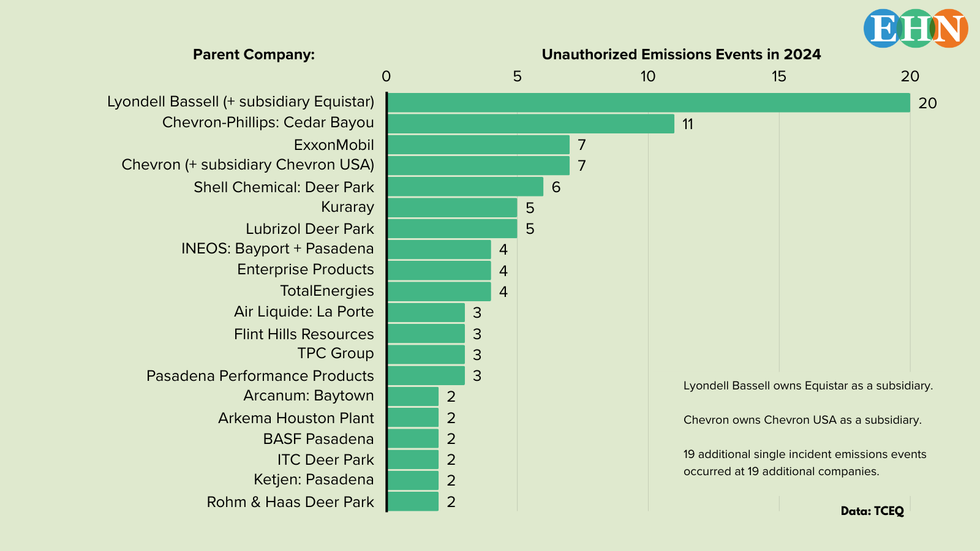

Many companies had multiple events in the past nine months, according to EHN’s analysis, with 97 incidents attributed to companies that had at least two events either at one or more locations.

LyondellBasell, a chemical company, had the most with 20, including events from their smaller company Equistar. With 11 incidents, Chevron Phillips Chemical Cedar Bayou plant had the most emissions events in a single location.

Some of the companies have environmental violations documented by the state’s TCEQ or the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). For example, Chevron Phillips Cedar Bayou plant has 545 TCEQ violations since 2011. In addition, in the past three years, the same facility had eight quarters of noncompliance with the Clean Water Act and 12 quarters of significant violations of the Clean Air Act. In addition, in 2022, Chevron Phillips Cedar Bayou plant — in addition to two other Chevron Phillips sites – was found by the Department of Justice and the EPA to have “failed to properly operate and monitor three chemical plant's industrial flares” causing “excess emissions of pollutants, including volatile organic compounds (VOCs), various hazardous air pollutants, including benzene and climate-change-causing greenhouse gasses” according to the EPA. The company paid $3.4 million in civil penalties and an additional $118 million in compliance actions.

“There is a toxic load our communities are forced to face. Unfortunately, you have regularity of flaring events, a lack of transparency for community members." - Shiv Srivastava, Fenceline Watch

One media representative from Chevron Phillips Chemical told EHN that they do not comment on their operations. However, a second representative, Lisa Trow, sent EHN an email stating that, “Chevron Phillips Chemical strives to ensure compliance, especially regarding flaring, and we are fully committed to environmental stewardship.” Trow also said that the company has worked to decrease emissions at its three sites included in the 2022 lawsuit with flaring reduction initiatives and additional control technologies, but did not say if those additions were a result of the compliance action fines.

EHN invited LyondellBasell to comment on their event history, but has not received a response.Flaring excess compounds

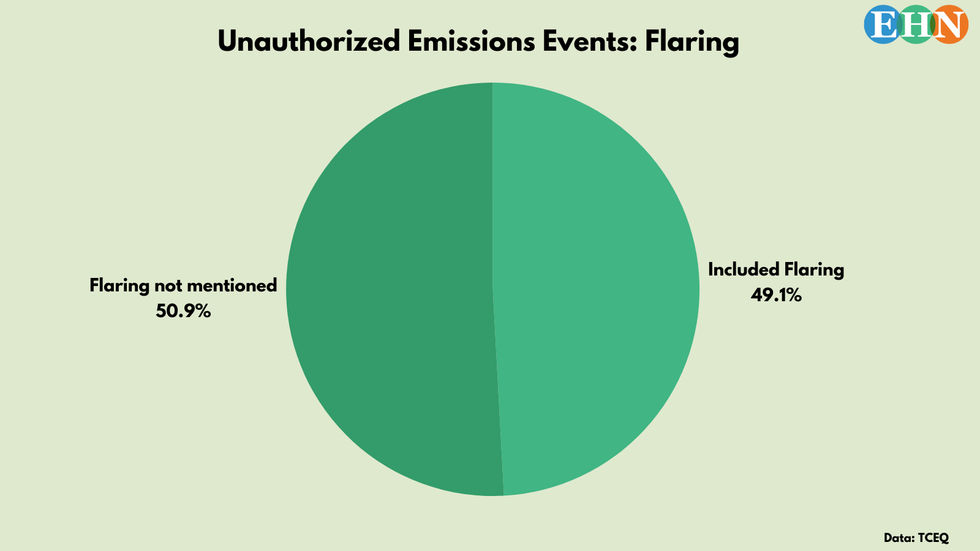

Flaring is just one type of a potential emissions event, but in 57 of the 116 events analyzed, flares were listed at least once. Some flaring emissions are covered under permits, while others are not. According to Peter DeCarlo, an associate professor of environmental health and engineering at Johns Hopkins University who studies atmospheric air pollution, flares are one of the most common sources of unauthorized emissions.

“Flaring … is done to actually reduce the emissions of some pollutants, but it results in the emissions of other pollutants,” DeCarlo told EHN. “It can also be a nuisance for noise or light reasons.

Flaring is often used to remove excess chemicals or to prevent larger issues like fires or explosions and is often considered preferable to releasing emissions directly into the atmosphere. But DeCarlo said flare emissions vary depending on what is burned. Typically the oil and gas industry will burn natural gas, resulting in the emissions of methane and carbon monoxide.

“Methane is much more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, and so by burning it off before it gets into the atmosphere actually reduces the impact to climate,” DeCarlo said. “That being said, it’d be great if we didn’t have to do that in the first place.”

DeCarlo noted that chemical industries, including petrochemical facilities, also flare, but may burn a larger variety of products including hazardous air pollutants that can pose health risks. Flaring destroys part of a chemical by burning it, and will turn it into something less harmful. While properly operating flares are expected to destroy 98% of emissions, DeCarlo said that can vary greatly.

“What’s typically assumed for efficiency is not what’s been seen or observed in field studies,” said DeCarlo. “These are often really hard measurements to make because flares are typically not at the ground so you are doing these measurements pretty high up in the air, trying to capture the air as it leaves the flare, and then back calculating how efficient it was.”

Things like wind, weather and maintenance can impact a flare. According to a 2022 study that surveyed three of the nation’s major gas production regions – Eagle Ford Shale, Permian Basin and Bakken – flares were destroying closer to 91.1% of methane, in some cases resulting in five times higher levels entering the atmosphere than previously assumed. Inefficient flares emit more pollutants like particulate matter, nitrogen oxides and carbon monoxide, according to DeCarlo. Additionally, some of the more concerning chemicals are not destroyed as much as desired.

“While they (flares) serve a purpose to reduce impact to climate or health, transitioning away from the use of fossil fuels would also minimize the need to have flares in the first place,” DeCarlo said.

In addition to climate related concerns, recent studies have documented flares’ health impacts. A 2020 study in Texas’ Eagle Ford Shale found mothers that live within about three miles of high levels of industrial flaring are 50% more likely to deliver premature babies. This likelihood increased for Latine parents. Another study found that flaring and venting – the release of ignited gas – contributed to an additional $7.3 billion in health risks and 710 premature deaths annually in the U.S.

“It’s so much more than just carbon being released,” Srivastava, of Fenceline Watch, said. “This is happening daily. At some facility right now, flaring is occurring.”

Cumulative pollution impacts

Residents near Harris County’s heavy industry that are more likely to be exposed to emissions events, like Srivastava, worry about cumulative exposure, gaps in information and that companies with multiple emissions events don’t face consequences.

The TCEQ investigates all emissions events reports that are filed with the agency to determine if there are inaccuracies in the reporting, if the incident could have been prevented, or if the incidents seem to be part of a recurring issue. If incidents are part of a recurring issue, they are investigated in relation to the specific facility, not the site as a whole. As of September 5, TCEQ media representative Victoria Cann said that 40 investigations had been completed this year, and 79 were still open. Additionally, in this process the TCEQ determines if the emissions should result in violations or corrective action.

While information about these emissions events are publicly available, DeCarlo warns that this information may not suffice.

“We almost universally find that the [ EPA’s toxic release inventory] and state inventories underestimate emissions, often very significantly,” he said.

Individuals wanting information about these events in real time in Harris County –an area with a high density of industrial presence – can visit the Community Awareness Emergency Response, portal, which is operated by the East Harris County Manufacturers Association. If you’d like to examine emissions events in other Texas communities, you can access the state database here. Federal data can be found here.