Old age, neglect and a changing climate are rendering US dams dangerous

In the face of more frequent and intense rainfall, dam failures are becoming the norm. What can be done with the underfunded relics?

Annapolis, Md.—DJ Buckley spent most of his afternoon on Aug. 3 picking up branches and debris out of the Annapolis Harbor.

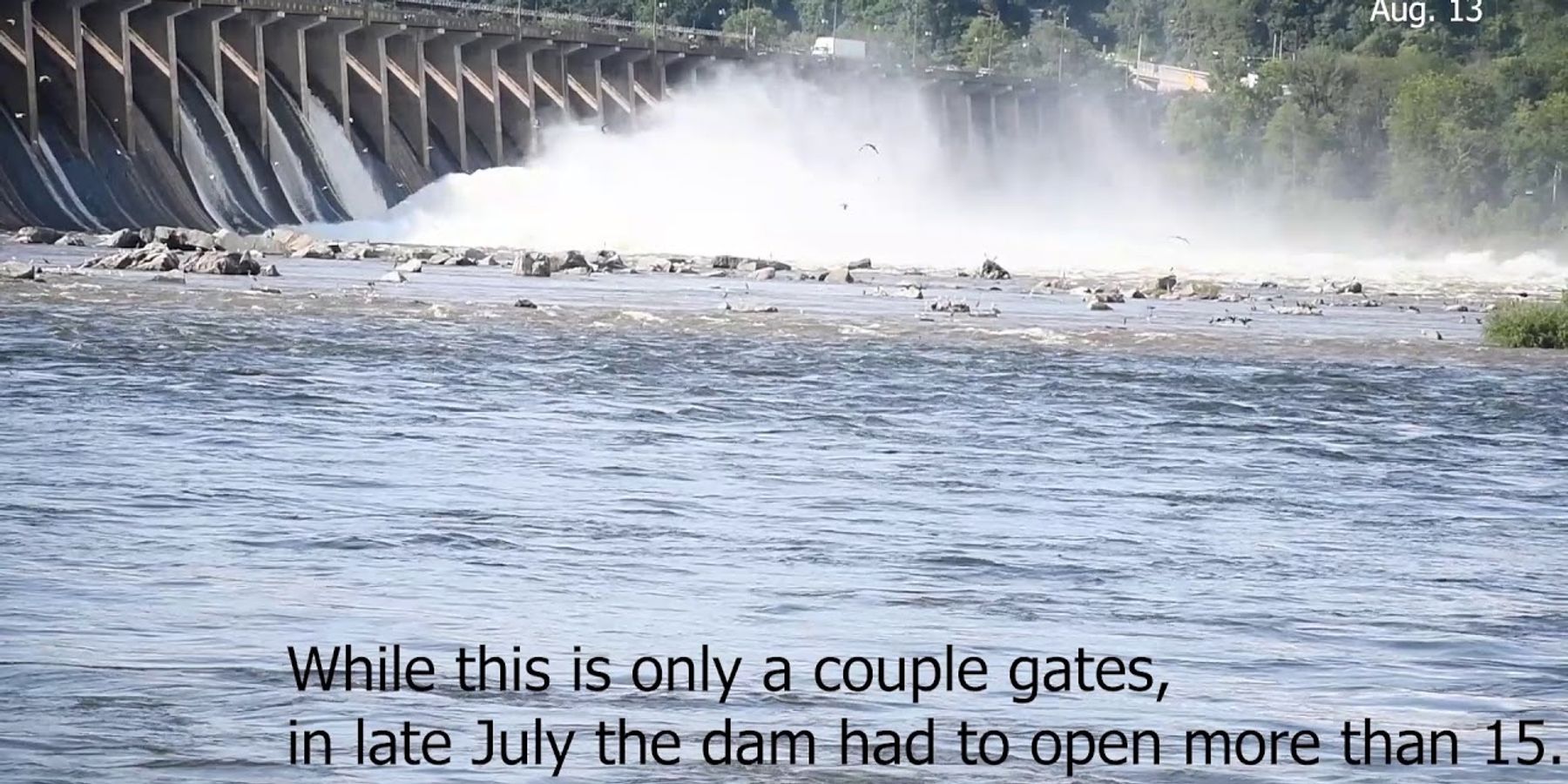

After the Conowingo Dam opened 17 floodgates due to rising water levels, built-up debris came washing through into the harbor.

"I can't remember a time when I've seen that much in here," Buckley said.

The debris in the harbor led Maryland Comptroller Peter Franchot to call out Pennsylvania for the amount of garbage and branches in the Susquehanna River, which flows through the Conowingo Dam and into the harbor.

The incident leads to more questions about dams in the U.S. While the Conowingo opening up its gates does not constitute as a failure, as storms become more intense due to the changing climate, there will be more overtopping at deficient dams, Mark Ogden, technical specialist with the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, told EHN.

Just this month in North Carolina, a dam at the state's retired Duke Energy plant failed, spewing ash and coal into the Cape Fear River. That dam had an emergency action plan, but the majority of the state's high-hazard dams do not.

That's not unusual.

Approximately 30 percent of the country's 15,498 high-hazard dams do not have emergency plans. Add in the age and lack of maintenance of many dams, and a flooding disaster is just waiting to happen. And in many places it has happened—according to the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, failures have occurred in every state, with at least 173 failures between 2005 and 2013.

"If you have more intense storms, more frequent storms then those deficient dams can't handle that. And you're going to see more problems where dams are under stress due to the high waters levels or the overtopping," Ogden said.

High hazards, low funding

There are more than 90,000 dams in the U.S., according to the National Inventory of Dams, which is kept by the Army Corps of Engineers. Approximately 15,500 of them are classified as high hazard, meaning in the case of failure, at least one life could be lost.

According to the Association of Dam Safety Officials, the average age of dams in the U.S. is 56 years old. By 2025, seven out of 10 dams will be 50 or older.

It would take approximately $22 billion to rehabilitate the most critical dams, according to the Association.

While the Army Corps keeps track of the amount of high, significant and low-hazard dams in the country, the individual hazard potential for each dam is not available for the public, Kathryn Van Marter, a spokeswoman with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, told EHN in an email.

But of the 15,498 high hazard dams in the country, 4,861 do not have emergency action plans or an emergency action plan is not required. Take Rhode Island: 79 of its 96 high hazard dams do not have emergency action plans.

"With the changing climate and the more intense rainstorms that we're getting, a lot of these dams were never designed to handle the kind of water we're going to be getting in the years to come," David Chopy, chief of the Office of Compliance and Inspection for Rhode Island, told EHN.

But Rhode Island is not alone. Alabama, Georgia, Florida, North Carolina and New Mexico have more high hazard dams without an emergency action plan than dams that do, according to the National Index of Dams. In Georgia, Indiana and Missouri, the majority of the dams are not required to have such a plan.

Related: Bringing back natural water filters in Maryland and beyond

That's just for high-hazard dams. There are also nearly 12,000 dams in the U.S. that are considered significant hazard, which means that they wouldn't cause potential loss of life, but they can cause economic and environmental distress if they fail. There are seven states that have more significant-hazard dams without emergency plans than dams that do.

Dams in Rhode Island are required to be inspected every two years if they are high hazard and every five years for significant hazard dams, Chopy said. But whether the dams are fixed after inspection is up to the owners.

The dam situation in Rhode Island is representative of dams across the U.S. Most dam owners are private and funding is a concern, Ogden said. Chopy said the lack of funding was the reason most of the high hazard dams in the state do not have an emergency action plan.

"They're not cheap to fix, and a lot of the owners are private property owners, and they don't have that kind of money to fix the dams. Even the ones that are owned by public entities, the cities and towns and the state, it's difficult to come up with that money to fix the dams," he said.

Every state but Alabama has some type of regulatory plan that allows for dam inspections, Ogden said.

There is a statewide dam inventory to identify and document dams that might be high-hazard, Alabama Department of Economic and Community Affairs spokesman Josh Carples told EHN in an email.

Why dams fail

A dam failure, as defined by the Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety, is a sudden, rapid and uncontrolled release of water, Van Marter said. A breach is an opening in the dam that allows uncontrolled draining.

Dams can fail a number of ways, Ogden said. Typically with a heavy flood, the spillway system will be topped, especially in dams that are poorly designed. Dams can be eroded by water, which would allow water to spill over.

And other natural disasters, like earthquakes, can damage them as well.

In addition, old dams weren't built to today's standards, Ogden said. The Army Corps of Engineers released the most recent safety guidelines for dams in 2014, but it notes that the federal organization has very limited control over repairs to non-federal dams. FEMA also has guidelines for dam safety.

Ogden said dams might need upgrades that they might not receive. Others just might not be maintained, which makes dams more likely to fail.

Others have seen an increase in hazard potential, Ogden said, due to added development around a dam.

Heading for heavier rains

University of Connecticut professor Guiling Wang told EHN that climate models predict heavier rains on a global scale. Wang, who published a 2017 article in Nature about temperature and precipitation, said that as the water cycle changes because of the warmer climate, the atmosphere can hold more water.

The increase in extreme precipitation can come at the expense of light or moderate precipitations, which might explain why there will be periods of no rain followed by intense downpours, according to Wang's Nature article.

However, the heavier rains are correlated with increased temperatures below a threshold. When temperatures reach above a threshold, there tends to be less rain.

That can lead to more rain over a short period of time or rain that doesn't stop, she said. On a global scale, Wang said she expects to see rain increase by 2 percent to 4 percent. And it's likely to lead to flooding, something that's already happening.

Pollution pressure

The Association of State Dam Safety Officials has a list of resources for people who live near dams. Ogden said it's important for people find out if there's a dam nearby and if that dam has an emergency action plan.

A good plan would have areas marked for flood risks and evacuations.

"I think the big thing people should do is be aware," Ogden said.

While hazard potentials are determined by loss of life or economic consequences following a failure, when dams fail or have to open floodgates, there can be environmental consequences.

"Environmental impacts of dam failure can include transport of sediment excess downstream, habitat loss, severe bank erosion and scouring, and contamination of environmentally sensitive areas," Van Marter said.

Franchot called the debris in the Annapolis harbor a "catastrophe." Maryland officials also called on Exelon, the operators of the Exelon dam to help with cleanup efforts.

"Parts of the Chesapeake Bay look like the aftermath of D-Day. It's disgusting," Franchot said.

The Conowingo Dam is not a source of the pollution, Exelon spokesman Paul Adams told EHN in an email.

"The debris currently in the Chesapeake Bay is a direct byproduct of record rain in the region," he said in the email.

It's clear that extreme rain and weather will come, and the debris that came through the Conowingo Dam is an example of why more pollution measures are needed, Maryland Secretary of the Environment Ben Grumbles told EHN.

Immediately after the pollution in the harbor, the focus was on cleanup. But a longer term strategy will focus more attention to the entire watershed, Grumbles said.

"It's clear that more precipitation, more runoff, more extreme weather is in store for the Bay and the tributaries to the Bay, so this is a shining example for the need for pollution prevention measures upstream and at the Conowingo Dam itself," he said.